Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

7 min read

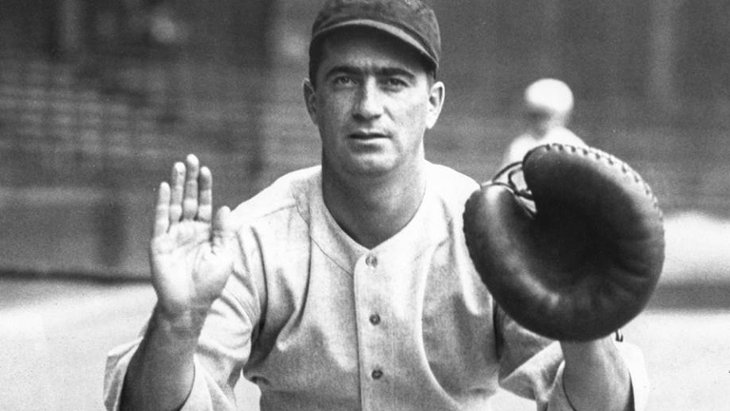

Moe Berg became a major league ball player and a major league spy.

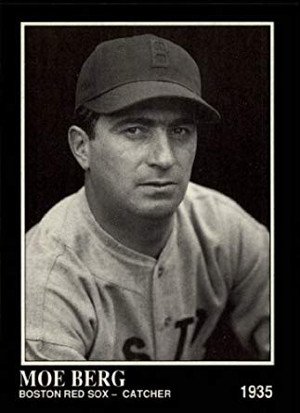

He was a Renaissance man, a combination of brain and brawn, the ultimate Jewish athlete. For 15 years in the 1920s-1930s, Morris ("Moe") Berg played for five major league teams: the Brooklyn Robins (later the Dodgers), Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians, Washington Senators, and the Boston Red Sox.

Yet he notched his most memorable plays not on the baseball diamond but in the high-stakes arena of intelligence gathering, both before and during World War II.

Handsome, brilliant, and daring, Berg was such a riveting and colorful figure that, as one commentator noted in the new documentary “The Spy Behind Home Plate,” directed by Aviva Kempner, if Moe Berg hadn’t existed, someone would have had to make him up.

Born in 1902 in New York to Bernard and Rose Berg, Moe grew up in an apartment above his father’s pharmacy in Newark, New Jersey. Going undercover even in childhood, Berg used an alias to join a boys’ baseball team at a local church, an act that infuriated his father, who considered baseball “nareishkeit” – foolishness. Bernard Berg, who had shoveled coal on a ship to pay his fare to America and who ran a laundry by day while studying pharmacy at night, couldn’t abide the thought that his son would throw away better career opportunities in America. He never attended a single game his son played, even in the major leagues.

Kempner also directed “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg,” and jumped at the chance to make a film about this underrecognized Jewish hero. Businessman William Levine had suggested she make the film and offered to support the effort.

“The Spy Behind Home Plate” includes 18 archival interviews conducted from 1987 to 1991 by filmmakers Jerry Feldman and Neil Goldstein, whose film about Moe Berg was never completed. Interviewees include Moe’s brother, Dr. Sam Berg; fellow players including Dom DiMaggio, fellow members of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and prominent biographers and sports writers.

Moe flouted expectations for what Jewish boys could achieve in the early years of the 20th century. He gained acceptance at Princeton University, which admitted very few Jews at the time, and played shortstop for their baseball team. He was invited to join one of the university’s prestigious eating clubs, but when he was told he couldn’t recruit other Jews to the club, he refused the invitation.

He graduated Magna Cum Laude in languages (he eventually learned ten of them), and despite a mediocre batting average, Berg was still signed by the Brooklyn Robins – the Empire State’s sizeable Jewish population assured his popularity. During the offseason, Moe loved to travel. In Paris, he studied Sanskrit at the Sorbonne, and, based on letters and photographs, also enjoyed an active nightlife in restaurants and clubs.

Berg also earned a law degree from Columbia, sometimes ditching baseball practice to attend class, but his law career was extremely short-lived. While playing catcher for the Chicago White Sox, he had a cartilage tear, a catastrophic injury at the time. He ran very slowly, but he could still hit.

A turning point in Berg's life came in 1934 when the U.S. sent an A-list line-up of ballplayers to play in Japan. Tensions were already high between the two countries, and the trip was meant as a goodwill gesture. The team included Lou Gehrig, Charlie Gehringer, Jimmy Fox, Babe Ruth, and Earl Averill. Moe Berg was a last-minute replacement for catcher Rick Ferrell. Berg not only spoke fluent Japanese but had also recently completed 117 consecutive games without an error.

Was Berg already involved in covert operations for the U.S.? Nobody knows for sure, but it is curious that Berg had a letter in hand from Secretary of State Cordell Hull asking that Japan give Berg “diplomatic courtesies” while in the country. During the trip, Berg also gave a radio address in Japanese, offering the hope that this trip would bring the two nations closer together.

Despite the highly militarized atmosphere and ubiquitous “no photography” signs, Berg took pictures everywhere with his state-of-the-art Bell & Howell camera. In Tokyo, this big, swarthy American Jew walked the streets with his hair parted in the middle and wearing a kimono and slippers. He arrived at St. Luke’s Hospital with flowers, asking to visit the daughter of the American ambassador, who had just given birth. Inside the hospital, Berg dumped the flowers and climbed the stairs to the rooftop, taking photographs of the city’s skyline in every direction.

When World War II broke out, Berg knew that FDR could not keep the U.S. out of the war. Berg had spent time in Berlin as well as Tokyo and had observed the militaristic and nationalistic tone in both countries. He knew that fascism could not be allowed to win out.

The U.S. was woefully behind Germany in intelligence gathering capabilities. This failure had catastrophic consequences, as proven by the attack on Pearl Harbor. Based on Berg’s voracious reading of books and international newspapers, as well as his own travels, he wrote a memo outlining what he felt would be essential in an American intelligence gathering agency and sent it to Bill Donovan, who became the first director of the OSS.

Berg served the OSS throughout the war, and his stealth photographs of the Tokyo skyline taken years earlier proved invaluable. Like all other OSS operatives, Berg had to be tested for loyalty, emotional stability, and intelligence before being sent abroad. Agents had to know how to blend in and not appear American, even by their dining habits. They also had to know how to pick locks, handle explosives, put a charge on a railroad track and be prepared to kill.

Berg's most remarkable achievements including tracking down Italian scientist Antonio Ferri, who was reputed to know everything that Germany was doing to prepare to make a nuclear bomb. Wanted by the Germans, Ferri buried a suitcase filled with secret information and then went into hiding in the mountains, behind German lines, and joined the resistance. Moe Berg found him before the Germans could and arranged for his rapid immigration to the U.S.

Berg's most remarkable achievements including tracking down Italian scientist Antonio Ferri, who was reputed to know everything that Germany was doing to prepare to make a nuclear bomb. Wanted by the Germans, Ferri buried a suitcase filled with secret information and then went into hiding in the mountains, behind German lines, and joined the resistance. Moe Berg found him before the Germans could and arranged for his rapid immigration to the U.S.

“I see that Moe is still catching very well,” President Roosevelt said upon hearing the news.

Berg was also sent to Zurich to attend a lecture by renowned German scientist Werner Heisenberg. This had to have been one of the most dangerous jobs anyone – particularly a Jew – could undertake. Wearing American-made shoes designed to copy German styles, but which were too tight and too narrow, Berg attended the lecture carrying both a loaded pistol and cyanide tablet. If Berg had understood Heisenberg to report that Germany was nearing completion of work on a nuclear bomb, he would have shot him and swallowed the cyanide. Berg couldn't fully understand the complex German lecture, but his reading of the room led him to believe Germany wasn't ready to detonate a nuclear bomb.

Berg even walked Heisenberg back to his hotel, where the scientist admitted that Germany was sure to lose the war. Among his other exploits were going into South America, ostensibly to give away baseball gear, but really to look for signs of Nazi infiltration. Some claim that Berg also parachuted into Yugoslavia and met with partisan leader Tito during the war, but Kempner said no hard evidence exists. “Unfortunately, this story is featured in several museums and exhibits,” she said.

Berg remained in Europe after the war, recruiting additional European scientists to come and work in America. He once had tea with Albert Einstein, who said, “Mr. Berg, if you teach me baseball, I will teach you the theory of relativity. Ach, never mind. I’m sure you’ll learn the theory of relativity faster than I’ll learn baseball.”

In his later years, Moe Berg became a familiar presence in the press boxes of major league baseball games, never losing his love of the sport. Reportedly, his last words to his nurse before he died at 70 were, “How did the Mets do today?”

For information about the film’s screenings, go to http://spybehindhomeplate.com