Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

5 min read

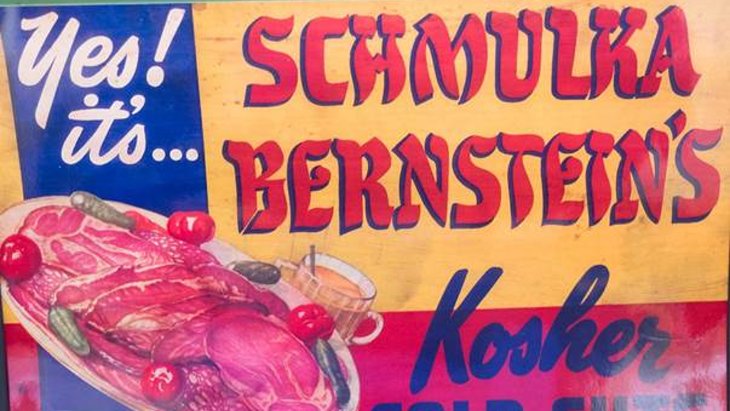

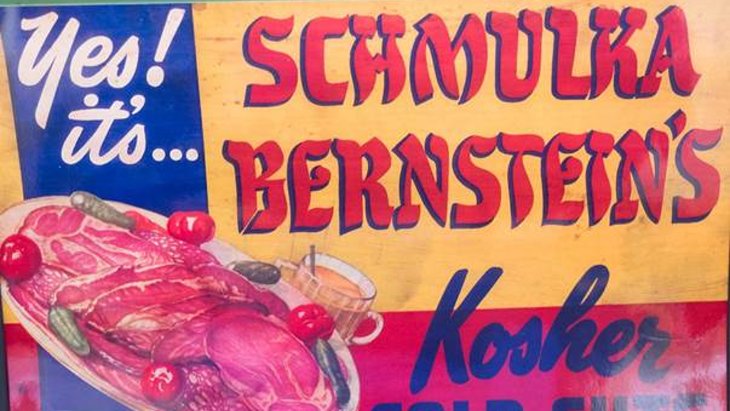

From Reuben’s in London to Schmulka Bernstein’s in New York’s Lower East Side, delis are dropping like flies.

It was recently announced that one of the most famous and beloved kosher restaurants in the world, Reuben’s in London, England, has closed its doors forever. Here is the formal announcement: “With a heavy heart, unexpectedly we have to close . . . We are proud that of the 46 years Reuben’s has served the community . . . We wish all our customers and friends the best wishes. Thank you for the good memories we have all shared! Love from all the Reuben family.”

For nearly half a century Reuben’s made sure that kosher London locals could enjoy a London broil and kosher tourists could enjoy a British brisket. Reuben’s closure has left a void on the global smorgasbord, a kosher carnivorous chasm that will leave deli devourers dwelling on the past with a heavy-heart (albeit one with less meaty cloggage).

What is it about the closing of a kosher restaurant, particularly a popular or well-established one, that triggers such intense longing for the bygone cuisine? When a classic kosher joint shuts its doors, why does it matter and hurt so much?

Reuben’s is not the only famous kosher haunt to fade from the kosher culinary landscape. The most well-known is probably Schmulka Bernstein’s, a former stalwart of the Lower East Side and a beautiful beacon for bloated borscht-belt bellies hoping to inhale the menschiest grub imaginable. It served both classic deli fare and authentic Cantonese cuisine and it’s slogan stated: “where kashrut is king and quality reigns.” (Given the diverse deli/Chinese menu, the slogan could have been “where corned beef is king and General Tso reigns.”) Schmulka Bernstein’s might very well be the quintessential kosher restaurant, the kingpin of kosher cooking and frelich fine dining. New York still has many kosher restaurants that aim to please but none hold a candle (or a knish, kreplach or kneidlach) to the legendary and irreplaceable Schmulka Berntsteins. It was not just about the food. It was the experience.

Sadly, other classic kosher restaurants also have come and gone. For example, Boston had Rubin’s Deli in Brookline for 90 years until its closing in 2016. Rubin’s had all of the trademarks of the true deli experience. Pickles and coleslaw hit the table within seconds, kreplach soup quickly stole the show and award-winning sandwiches with mountains of meat captivated crowds. The pastrami was insanely delicious and the corned beef was preposterously delectable. It was quite a show and a shame it had to go. You can still find quality kosher grub in the area, especially at Mamaleh’s, Rami’s and elsewhere, but the loss of the Bostonian Rubin’s, like that of the British Reuben’s, has left a gaping whole that may never be filled.

Kosher Canadians also have suffered a great loss on the restaurant scene. For over 30 years, Montreal was home to a phenomenal kosher Morrocan restaurant fittingly named El Morocco. Located in the heart of the city, El Morocco served tasty tajine and dreamy dwaz like they were going out of style, until the place unfortunately went out of business. While open, however, the authentic food tasted like it had been flown in from Fez. After a few bites, you felt as though you had been transported to magical Marrakesh. El Morocco was a mouth-watering adventure that very few kosher restaurants can match. For several years, New York City had a similar Morroco-themed kosher restaurant called Darna that also was quite good but they disappointingly went of business too, thus putting the “darn” in Darna.

New Orleans used to feature a wonderful kosher restaurant charmingly named Creole Kosher Kitchen. It was conveniently located in the French Quarter and offered an excellent kosher facsimile of local New Orleans cuisine but with a traditional Jewish twist. In other words, they bridged the gap between gumbo and cholent and they turned the Po’Boy into the Po’Boychick. The Creole Kosher Kitchen, however, ceased operations in New Orleans, a massive loss that, for kosher-keepers, created southern discomfort that really stuck in their craw(fish). Faux crawfish, that is.

For the record, the loss of classic kosher restaurants has not affected the fleishig field only. Milchig or pareve places also have been hit and none more devastating than Ratner’s on the Lower East Side. Founded in the early 1900’s, Ratner’s took the kosher deli concept and applied it to non-meat treats like blintzes, pierogies, smoked fish, kasha varnishkes and borscht. The portions were generous and the style was heartwarming, like eating at your grandparents’ house. Of course, no Ratner’s meal was complete without their famous onion rolls, each arguably more onion than roll. Ratner’s was an institution and it’s closing likely caused some to be institutionalized. That might sound crazy but the loss of a quality kosher restaurant can push loyal customers over the edge and cause them to flip their lids (but not their kippot.)

Final thought: When a relationship ends, closure is good. When a kosher restaurant ends, closure is not so good.