Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

15 min read

Examining the historicity of the biblical exodus.

The following is adapted from the author’s new book, Ani Maamin: Biblical Criticism, Historical Truth and the Thirteen Principles of Faith (Maggid, 2020).

Thanks in no small part to the Internet and the ubiquity of social media, popular exposure to the findings of biblical criticism has increased exponentially. And much of it focused on one issue: the historicity, or especially the non-historicity, of the biblical exodus. Here I’d like to offer an academic defense for the plausibility of the exodus event.

The case against the historicity of the exodus is straightforward, and its essence can be stated in five words: a sustained lack of evidence. Nowhere in the written record of ancient Egypt is there any explicit mention of Hebrew or Israelite slaves, let alone a figure named Moses. There is no mention of the Nile waters turning into blood, or of any series of plagues matching those in the Bible, or of the defeat of any pharaoh on the scale suggested by the Torah’s narrative of the mass drowning of Egyptian forces at the sea.

No competent scholar or archaeologist will deny these facts. Case closed, then? For those who would defend the plausibility of a historical exodus, what possible response can there be?

Let’s begin with the missing evidence of the Hebrews’ existence in Egyptian records. It is true enough that these records do not contain clear and unambiguous reference to “Hebrews” or “Israelites.” But that is hardly surprising. The Egyptians referred to all of their West-Semitic slaves simply as “Asiatics,” with no distinction among groups – just as slave-holders in the New World never identified their black slaves by their specific provenance in Africa.

More generally, there is a limit to what we can expect from the written record of ancient Egypt. Ninety-nine percent of the papyri produced there during the period in question have been lost, and none whatsoever has survived from the eastern Nile delta, the region where the Torah claims the Children of Israel resided. Instead, we have to rely on monumental inscriptions, which, being mainly reports to the gods about royal achievements, are far from complete or reliable as historical records. They are more akin to modern-day résumés, and just as conspicuous for their failure to note setbacks of any kind.

We’ll have reason to revisit such inscriptions later on. But now let’s consider the absence of specifically archaeological evidence of the exodus. In fact, many major events reported in various ancient writings are archaeologically invisible. The migrations of Celts in Asia Minor, Slavs into Greece, Arameans across the Levant – all described in written sources – have left no archeological trace. And this, too, is hardly surprising: archaeology focuses upon habitation and building; migrants are by definition nomadic.

There is similar silence in the archaeological record with regard to many conquests whose historicity is generally accepted, and even of many large and significant battles, including those of relatively recent vintage. The Anglo-Saxon conquest of Britain in the 5th century, the Arab conquest of Palestine in the 7th century, even the Norman invasion of England in 1066: all have left scant if any archaeological remains. Is this because conquest is usually accompanied by destruction? Not really: the biblical books of Joshua and Judges, for instance, tell of a gradual infiltration into the land of Israel, with only a small handful of cities said to have been destroyed. And what is true of antiquity holds true for many periods in military history in which conquest has in no sense entailed automatic destruction.

Actually, there is more to be said than that. Many details of the exodus story do strikingly appear to reflect the realities of late-second-millennium Egypt, the period when the exodus would most likely have taken place – and they are the sorts of details that a scribe living centuries later and inventing the story afresh would have been unlikely to know:

To sum up thus far: there is no explicit evidence that confirms the exodus. At best, we have a text – the Tanakh – that exhibits a good grasp of a wide range of fairly standard aspects of ancient Egyptian realities. This is definitely something, and hardly to be sneezed at; but can we say still more? I believe that we can.

One of the pillars of modern critical study of the Bible is the so-called comparative method. Scholars elucidate a biblical text by noting similarities between it and texts found among the cultures adjacent to ancient Israel. If the similarities are high in number and truly distinctive to the two sources, it becomes plausible to maintain that the biblical text may have been written under the direct influence of, or in response to, the extra-biblical text. Why the one-way direction, from extra-biblical to biblical? The answer is that Israel was largely a weak player, surrounded politically as well as culturally by much larger forces, and no Hebrew texts from the era prior to the Babylonian exile (586 BCE) have ever been found in translation into other languages. Hence, similarities between texts in Akkadian or Egyptian and the Tanakh are usually understood to reflect the influence of the former on the latter.

Comparative method can yield dazzling results, adding dimensions of understanding to passages that once seemed either unclear or self-evident and unexceptional. As an example, consider how at the Seder table we recall how God delivered Israel from Egypt “with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.” Most would be surprised to learn that this biblical phrase is actually Egyptian in origin: Egyptian inscriptions routinely describe the Pharaoh as “the mighty hand” and his acts as those of “the outstretched arm.”

Why would the book of Exodus describe God in the same terms used by the Egyptians to exalt their pharaoh? We see here the dynamics of appropriation. During much of its history, ancient Israel was in Egypt’s shadow. For weak and oppressed peoples, one form of cultural and spiritual resistance is to appropriate the symbols of the oppressor and put them to competitive ideological purposes.

In contemporary times a good example of this was seen in Israel during Operation Protective Edge, the last round of conflict with Hamas in 2014. Hamas leaders in Gaza produced a Hebrew language propaganda video aimed for the Israeli home front. Featuring a jingle “Arise! Attack!,” it displayed Hamas terrorists launching missiles at Israeli civilian targets. But the video backfired. Israelis immediately began producing spoofs of “Arise, Attack,” in soulful piano, and a capella. “Arise!, Attack!” was a must-play track at weddings. Israelis were demonstrating the dynamics of appropriation: taking the symbols and propaganda of those who threaten them, and re-employing them as tools of cultural resistance.

But in its telling of the exodus, the Torah appropriates far more than individual phrases and symbols. In fact, it adopts and adapts one of the best-known accounts of one of the greatest of all Egyptian pharaohs. The paramount achievement of Ramesses II (reigned 1279-1213 BCE) – known also as Ramesses the Great--occurred early in his reign, in his victory over Egypt’s arch-rival, the Hittite empire, at the battle of Kadesh: a town located on the Orontes River on the modern-day border between Lebanon and Syria. It is believed to have been the largest chariot battle in history. Upon his return to Egypt, Ramesses inscribed accounts of this battle on monuments all across the empire. Ten copies of the work, known as the Kadesh Poem, exist to this day. These multiple copies make the battle of Kadesh the most publicized event in the ancient world. Many Egyptologists believe that the Kadesh Poem was a widely disseminated “little red book,” aimed at stirring public adoration of the valor and of Ramesses the Great.

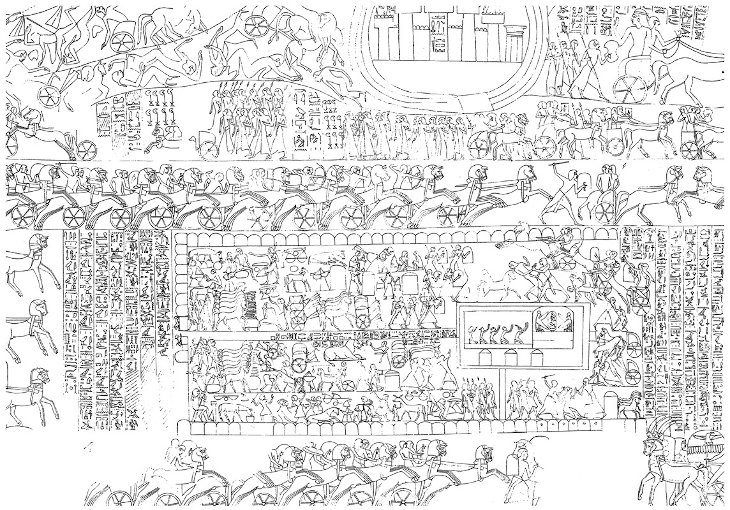

Some 80 years ago, scholars noted an unexpected affinity between the biblical descriptions of the Tabernacle and the illustrations of Ramesses’ camp at Kadesh in several bas reliefs that accompany the Kadesh Poem. In the image below of the Kadesh battle, the walled military camp occupies the large rectangular space in the relief’s lower half:

The throne tent of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel. W. Wreszinski, Atlas zur altägyptischen Kulturgeschichte Vol. II (1935), pl. 169.

The throne tent of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel. W. Wreszinski, Atlas zur altägyptischen Kulturgeschichte Vol. II (1935), pl. 169.

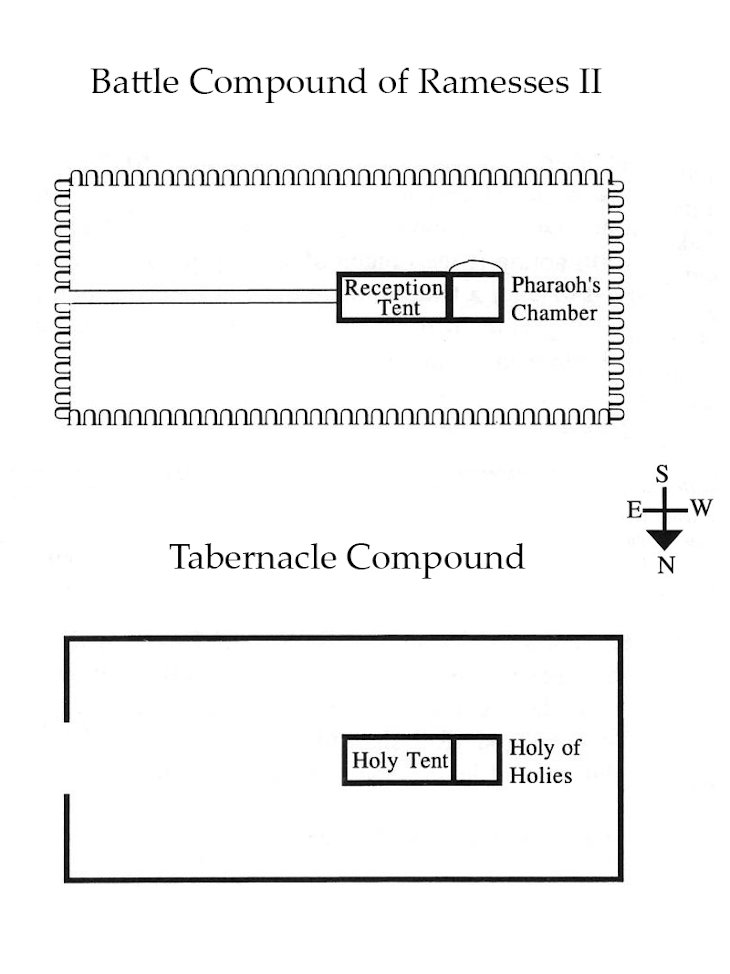

The camp is twice as long as it is wide. The entrance to it is in the middle of the eastern wall, on the left. (In Egyptian illustrations, east is left, west is right.) At the center of the camp, down a long corridor, lies the entrance to a 3:1 rectangular tent. This tent contains two sections: a 2:1 reception tent, with figures kneeling in adoration, and, leading westward (right) from it, a domed square space that is the throne tent of the pharaoh. All of these proportions are reflected in the prescriptions for the Tabernacle and its surrounding camp in Exodus 25-27, as the two diagrams below make clear:

To complete the parallel, Egypt’s four army divisions at Kadesh would have camped on the four sides of Ramesses’ battle compound; the book of Numbers (ch. 2) states that the tribes of Israel camped on the four sides of the Tabernacle compound.

Some scholars suggest that the Bible reworked the throne tent ideologically, with God displacing Ramesses the Great as the most powerful force of the time.

With my interest piqued by the visual similarities between the Tabernacle and the Ramesses throne tent, I decided to have a closer look at the textual components of the Kadesh inscriptions, to learn what they had to say about Ramesses, the Egyptians, and the battle of Kadesh. What I realized is that the similarities extend to the entire plot line of the Kadesh poem and that of the splitting of the sea in Exodus 14-15. It is reasonable to claim that the narrative account of the splitting of the sea (Exodus 14) and the Song at the Sea (Exodus 15) reflects a deliberate act of cultural appropriation. If the Kadesh inscriptions bear witness to the greatest achievement of the greatest pharaoh of the greatest period in Egyptian history, then the book of Exodus claims that the God of Israel overmastered Ramesses the Great by several orders of magnitude, effectively trouncing him at his own game.

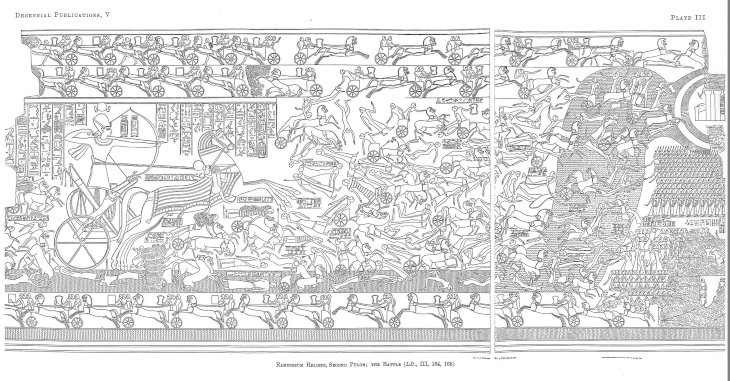

The two accounts follow a similar sequence of motifs and images seen nowhere else in the battle accounts of the ancient Near East. Here are the main parallel elements: Ramesses’ troops break ranks at the sight of the Hittite chariot force, just as Israel cowers at the sight of the oncoming Egyptian chariots. Ramesses pleas for divine help, just as Moses does and is encouraged to move forward with victory assured, just as Moses is assured by God. Bas reliefs depict the Hittite corpses floating in the Orontes River:

Most strikingly, Ramesses’ troops return to survey the enemy corpses. Amazed at the king's accomplishment, the troops offer a victory hymn that includes praise of his name, references to his strong arm, and tribute to him as the source of their strength and their salvation. Likewise, The Israelites survey the Egyptian corpses and offer a hymn of praise to God – the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15 – that contains many of the same motifs found in the hymn of praise by Ramesses’ troops. Ramesses consumes his enemy “like chaff” (cf. Exodus 15:7). Both the Kadesh Poem and the Exodus Sea account conclude with the “king” (Ramesses and God respectively) leading his troops peacefully home, intimidating foreign lands along the way, arriving at the palace, and being granted eternal rule.

The latest copies of the Kadesh Poem in our possession are from the reign of Ramesses himself, and there are no references to it, or clear attempts to imitate it, in later Egyptian literature. There is no evidence that any historical inscriptions from ancient Egypt ever reached Israel. This suggests that it is unlikely that an Israelite scribe living centuries later would have known about the Kadesh Poem, let alone borrow from it to inspire his own people.

Proofs exist in geometry, and sometimes in law, but rarely within the fields of biblical studies and archaeology. As is so often the case, the record at our disposal is highly incomplete, and speculation about cultural transmission must remain contingent. We do the most we can with the little we have, invoking plausibility more than proof. The parallels I have drawn here do not “prove” the historical accuracy of the Exodus account, certainly not in its entirety. But the evidence adduced here can be reasonably taken as indicating that the poem was transmitted during the period of its greatest diffusion, which is the only period when anyone in Egypt seems to have paid much attention to it: namely, during the reign of Ramesses II himself. In appropriating and “transvaluing” the well-known composition of the Kadesh Poem of Ramesses II, the Torah puts forward the claim that the God of Israel had far outdone the greatest achievement of the greatest earthly potentate.

While all this may be compelling as an argument for the historicity of an Exodus event – is it kosher? Can we actually say that God borrows pagan texts – even if only to polemicize against them – and incorporates them into his Holy Torah? Maimonides, for one, believed so. Maimonides writes that he searched high and low to learn as much as he could about the ancient Near East, and in his Guide to the Perplexed bemoans the fact that he didn’t know more about the subject. For Maimonides many of the mitzvot pertaining to sacrificial worship in the Temple, were, in fact, adaptations of pagan practices. Maimonides believed that the Torah took forms of worship that were familiar to the Israelites in Egypt and tweaked them in a way that bring them closer in line with monotheistic belief. The medieval exegete R. Levi b. Gershom (Ralbag) states that the Torah God wrote was written utilizing the literary conventions of the times (commentary to the Torah, very end of Sefer Shemot). And Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, was fully comfortable with the idea that there may have been inspiring stories and just laws that pre-existed the Torah, that were then chosen by God for inclusion in his holy Torah.

When we gather on the night of Passover to celebrate the exodus and liberation from Egyptian oppression, we can speak the words of the Haggadah with honesty and integrity: “We were slaves to a pharaoh in Egypt.”

Click here to order your copy of Ani Maamin: Biblical Criticism, Historical Truth and the Thirteen Principles of Faith (Maggid, 2020)

Material in this essay first appeared in Mosaic Magazine (https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/history-ideas/2015/03/was-there-an-exodus/).

It should be noted also that - some archaeology researchers - have written that - USING the sophisticated ELECTRONIC LIDAR. This showed that many of the Egyptian writings - were scraped off - and were rewritten - to accommodate - the then current political writings - which would not denigrate - the current - or a still popular ruler.