Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

4 min read

3 min read

4 min read

7 min read

For my Russian great-grandparents, being Jewish was like an ugly ghost.

I remember the day I saw the book at a charity shop in Pretoria, South Africa. The old yellowed pages, Hebrew letters, a Yom Kippur prayer book. I took it off the shelf and looked at the copyright date: Hamburg 1933. Cold shivers ran up my spine. I wondered what happened to the book’s owners.

“One day I'll be able to read the Hebrew,” I promised to myself as I took it to the shop assistant.

"Oh, a Jewish book," she smiled as she took my money. "Are you going to use it for research?"

"I'm Jewish," I replied.

"Oh I should have noticed," she said, pointing at the Star of David around my neck. "But you don’t look it," she said in a tone that implied she meant it as a compliment.

You don’t look it, the words rang in my head as I left the shop. The words hurt. If she spat in my face and called me a dirty Jew I would have felt better.

As I walked on, I thought about my great-grandparents and the reaction that they would have had to the saleslady’s words. I guess they would have been relieved.

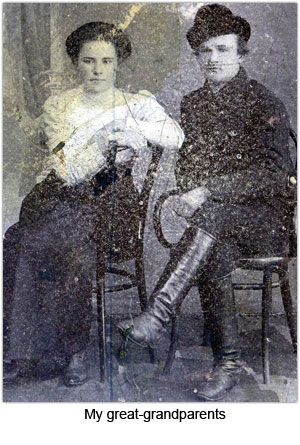

I have a picture of them at home, framed and sitting on my desk, a young couple on their wedding day before the First World War. They look serious as newlyweds often did in those days and both are oblivious to the future that awaited them. Pogroms, war, the Russian Revolution, civil war, the near starvation of the 1930s, Stalin, Hitler and the fear. Fear pervaded everything, overwhelmed all. There was no time to think, only to survive.

I have a picture of them at home, framed and sitting on my desk, a young couple on their wedding day before the First World War. They look serious as newlyweds often did in those days and both are oblivious to the future that awaited them. Pogroms, war, the Russian Revolution, civil war, the near starvation of the 1930s, Stalin, Hitler and the fear. Fear pervaded everything, overwhelmed all. There was no time to think, only to survive.

But it wasn’t always that way. Back in the days of that wedding picture, my great-grandfather was a successful accountant and my great-grandmother a proud owner of a beautiful house. But soon it all fell apart. The Russian Revolution took most of everything they had and in the ensuing civil war my great-grandmother was nearly murdered in a pogrom.

She never spoke about it, and it was only once that she cryptically referred to "hiding in a cellar for three days, with her small daughters." The memory of that incident passed down the ensuing generation like an ugly ghost.

My great-grandparents decided to erase all the outward signs of their Jewishness.

It was from that moment that my great-grandparents decided to erase all the outward signs of their Jewishness. While they never converted to another religion, they gradually ceased to observe most of the Jewish rituals, although my great-grandmother clung stubbornly to the laws of Kashrut and passed them onto her daughters, without explaining the meaning behind them. They would later refer to them as "Mama’s peculiarities."

The Minyan Incident

They passed several years like that, secure in their hidden identity until the Minyan incident.

It was in the late 1930s, in a small Russian town of Tara that my family finally lost its identity. There was a death in the community and the men went around looking for Jewish men to make up the Minyan, the quorum of 10 men. My great-grandfather was the only man they could find. He joined them and the following day the entire group was arrested and charged with ‘Religious Propaganda’.

My great-grandfather was sentenced to prison and his wife was advised to divorce him to make it known that she didn’t share his beliefs. Alone, and with six children to care for, she agreed. Nonetheless the government confiscated their belongings and continued to harass her for many years.

My great-grandparents stayed divorced for the rest of their lives. When my great-grandfather was released some eight years later, he returned home, but to keep up the appearances he had to live in a converted tool shed, away from the rest of the family. My great grandparents obtained a civil divorce, not a religious one. From then on no mention was made of my family’s Jewishness, not even behind closed doors. Some of the children were still small and small children talk.

My grandmother grew up terrified of her own heritage. My own mother recalls an incident when, aged five, she asked her mother, "What is a Jew?" and the look of horror on her mother’s face as she shrieked to her relatives, "Who told her?!"

But there was another feeling my mother remembers well – the feeling of not belonging, of some fundamental, unexplainable difference to the Russian children around her. The feeling never left. The rest of the family assimilated into the Russian society, intermarried and some converted to Christianity. After a while family "peculiarities" about pork and the mixing of dairy and milk products were forgotten.

My Phantom Pain

I grew up devoid of any knowledge of anything Jewish, but I also had that same haunting feeling that I was missing something. That longing, inexplicable and impossible to ignore, dominated my life. I called it my "Phantom Pain." Unable to identify it, I was angry and bitter and unpleasant to be around.

I grew up devoid of any knowledge of anything Jewish, but I also had that same haunting feeling that I was missing something.

It was in my late teens that I turned to Judaism. My initial reason for doing so was teenage rebellion and the defiance of all the things my family stood for. Only I wasn’t alone in my journey; my mother also rediscovered her roots and quietly returned to the faith of her ancestors.

My own journey was less peaceful.

I began by observing Shabbat and keeping kosher, without believing in God. I am a Jew and there is no way I am giving it up, I told myself. But I still wasn’t interested in learning the Torah. I looked up basic Judaism in the reference books and decided that it should be enough to keep me Jewish. But the more I read, the more I wanted to know. Gradually my knowledge began to change me.

I found myself looking forward to the High Holidays and a chance to think about myself. The days between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur were the best days of my life. As I thought about myself and my attitude, I underwent a complete transformation. I remember thinking that if I was making everyone around me miserable, what was the point of being alive? I wanted to do teshuva, to change. The feeling of being liberated from the anger and bitterness was so overwhelming, I felt myself reborn.

Today, nearly ten years later, I am at the ripe old age of 28 an enormously wealthy person. I am wealthy in my heritage and in my faith. Perhaps my treasures are dearer to me because I almost lost them. Dearer to me, because I had to gather them bit by bit, like a mosaic revealing the most beautiful picture I have ever seen.

My great-grandparents thought they were shielding us from the hatred that we would inevitably encounter as Jews. Unwittingly, they brought about a life of inferiority that came from denial. Changing their names, blending in and assimilating robbed us of the greatest treasure they didn't realize they possessed: the wonderful freedom and peace that comes with Jewish faith.

As the power of Yom Kippur demonstrates, the Almighty's arms are wide open, beckoning us to come home.