Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

Jewish Geography

Jewish Geography

13 min read

A majority of Jews live in Israel but millions of Jews remain scattered across the globe. Here are five little-known Jewish communities.

After 2,000 years of exile, today a majority of the world’s Jews live in the Land of Israel. But millions of Jews remain scattered across the globe. Here are five little-known Jewish communities.

The city of Iquitos, in northern Peru, is tucked deep in the rainforest. It is the largest city in the world inaccessible by road; people and supplies have to be flown in, or else chart the treacherous waters of the Amazon by boat. Iquitos is also distinct for being home to one of the world’s least-known Jewish communities.

The first Jew to arrive in this remote area was Alfredo Coblentz, who moved from Germany to the nearby town of Yurimaguas in 1880 to work in the Amazon’s booming rubber industry. Five years later, three brothers – Moises, Abraham and Jaime Pinto – moved to Iquitos to work in the rubber field. Though they stayed only a few years, Iquitos soon became known in Jewish circles as a place where there was a Jewish community. Jews from Morocco soon tried their luck Iquitos. Boats ferried would-be rubber traders from the Moroccan cities of Rabat, Tetuan, Tangier and Casablanca to the Brazilian coastal town of Belen do Para. From there, the Jewish traders trekked through the dense rain forest to reach Iquitos and neighboring Amazonian towns.

The historic Jewish cemetery in Iquitos, April 2013. (Facebook)

Iquitos flourished. Many traders built beautiful homes. One Iquita house, Casa Fierro, was designed by Gustave Eiffel, of Eiffel Tower fame. The Jewish community established a formal board, the Sociedad Beneficiencia Israelita de Iquitos in 1909, and flourished. Several Jews served as mayor of Iquitos, and Jewish families established businesses in town. In the early 1900s, when anti-Semitism drove many Ashkenazi Jews out of Europe, some settled in the booming city of Iquitos.

The Jewish community of Iquitos lights candles on Rosh Hashanah eve, 2016. (Facebook)

The Jewish community of Iquitos lights candles on Rosh Hashanah eve, 2016. (Facebook)

By the 1920s, cheaper rubber from the Far East had undercut Peru’s industry and Iquitos fell into depression. After the State of Israel was established in 1948, the vast majority of Iquitos’ Jews emigrated to the Jewish state. Many of those who remained moved to Lima, Peru’s capital, where there is an established Jewish community. Some descendants of the Jewish community remained in Iquitos, however. Even though many of these grandchildren and great-grandchildren became Catholic, they still remembered their Jewish origins.

In the 2000s, Jewish leaders began visiting Iquitos, and teaching the few remaining Jews about their heritage. This sparked renewed interest about all things Jewish. Several Iquitos residents with Jewish heritage have converted to Judaism and moved to Israel The Israeli town of Ramle has emerged as a hub of the Iquitos community in Israel. Today, the Jewish-descended community in Iquitos numbers about 70. In 2009, a Torah that was rescued from Nazi Germany was donated to Iquitos. As the descendants of Iquitos’ Jewish community continue to learn more about their heritage, a new symbol has emerged, binding the community together: an Israeli flag.

Formerly called German South West Africa, Namibia – a barren country bordering South Africa, Zambia, Angola and Botswana – has been home to Jews since the mid-1800s. In 1861, Jewish businessmen from Cape Town in South Africa established a trading post along Namibia’s coast, and helped build the region’s nascent copper mining industry.

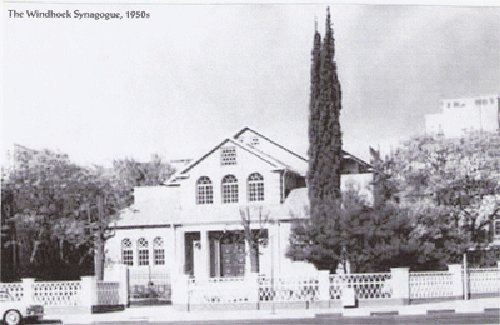

After Namibia became a German colony in 1884, a number of German Jews helped build up the country: Carl Fuerstenberg, a Jewish banker, helped finance railroads in his country’s newest colony; Emil Rathenau helped form the German South West African Mining Syndicate and funded irrigation projects. In 1917, about 20 Jewish families founded the Windhoek Hebrew Congregation in Windhoek, Namibia’s capital; eight years later, they built a synagogue. In 1927, a second synagogue was built in the town of Keetmanshoop.

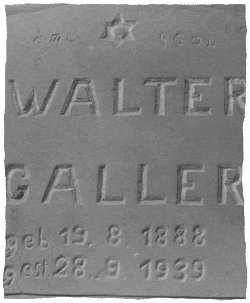

Jewish life in Namibia was always isolated. One Jewish grave in a remote part of the country bears vivid testimony to the difficulty of obtaining Jewish items. When an elderly Jew died, he asked his family to include some Hebrew writing on his grave. They buried him, using the only Hebrew script they could find: his gravestone reads “Here lies Walter Galler, Kosher L’Pesach (Kosher for Passover).” The Hebrew writing is upside down.

Jewish life in Namibia was always isolated. One Jewish grave in a remote part of the country bears vivid testimony to the difficulty of obtaining Jewish items. When an elderly Jew died, he asked his family to include some Hebrew writing on his grave. They buried him, using the only Hebrew script they could find: his gravestone reads “Here lies Walter Galler, Kosher L’Pesach (Kosher for Passover).” The Hebrew writing is upside down.

While Jewish life was slowly establishing itself in parts of Namibia, elsewhere German forces were testing out some ideas and practices that would be repeated a generation later in the Holocaust. German soldiers forced Namibia’s indigenous tribes further into the region’s interior desert, and German scientists rushed to Namibia to conduct grisly experiments. Josef Mengele, then a medical school professor, studied Namibians (referring to them as “subhumans”). Heinrich Goering, the father of Hitler’s Vice-Chancellor Hermann Goering, served as Governor of the colony. In 1904, the Kaiser gave orders for genocide, instructing German officials to wipe out the indigenous Herero Tribe. Over 65,000 Herero and other native people were murdered.

South Africa took over Namibia in 1915, and the Jewish community flourished for a while as an offshoot of South Africa’s larger community. By the late 1970s, 1,280 Jewish families called Namibia home. Five synagogues operated in Namibia. Today, only about 90 Jews call Namibia home.

A vast country spanning over 7,000 islands and boasting a population of over 100 million, the Philippines has dominated world headlines in recent years for its battles with Islamist terrorists in the nation’s south, and for its 2016 election of Pres. Rodrigo Duterte, who’s boasted of encouraging and carrying out vigilante killings of people accused of drug-dealing and other crimes. Less well known is that 0.0005% of the Philippines’ population is Jewish, in one of Asia’s least-known, but vibrant, communities.

Jews first arrived in the Philippines in the 1500s when it was a colony of Spain, thus under the law of the Spanish Inquisition. Two Jewish brothers, Jorge and Domingo Rodriquez, arrived in Manila in the 1590s and were soon tried and convicted of practicing Judaism, along with several other Jews.

The next record of Jews in the region is much more recent: 1870, when three Jewish brothers fled to the colony from France to escape the Franco-Prussian War. They soon set up a thriving import business, bringing Swiss watches, early automobiles, perfumes and medicines into the Philippines.

After the Suez Canal was built, the Philippines grew as a trading route between Asia and Europe, and Sephardic Jewish traders from the Middle East began working and settling in the Philippines. One Syrian Jewish businessman, A. N. Hashim, arrived in Manila in 1892 with a suitcase of watches to sell: soon he built a business empire, and eventually built Manila’s Grand Opera House. This small Sephardic community was soon bolstered by American troops fighting the Philippine-American war after the US took over the Philippines as a colony in 1898 (following the defeat of Spain, the Philippines’ previous colonial ruler, in the Spanish-American War). Several of the 70,000 American troops that fought in the Philippines were Jewish, and some decided to stay in the island colony. One notable serviceman who remained was John M. Switzer, a classmate of Herbert Hoover at Stanford. Mr. Switzer was an astute businessman and soon built up a canned goods business throughout the Philippines.

By 1917, the first synagogue was established in the Philippines; by 1925 about 200 Jews called the Philippines home. A National Jewish Welfare Board arranged for the importation of kosher food, wine and matzah on Passover.

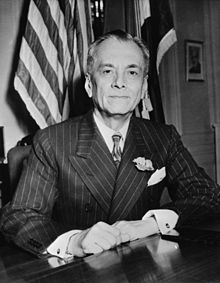

Manuel Quezon

Manuel Quezon

As Jews faced increasing restrictions and danger in Europe, Manuel Quezon, the first president of the Philippine Commonwealth, was concerned and wanted to help. One day, over a poker game with General Dwight D. Eisenhower and some prominent American Jews, Pres. Quezon hatched a plan to welcome 10,000 Jews to the Philippines. The United States refused to allow any poor people into the territory, so Pres. Quezon targeted prominent European Jews. Starting in 1938, about 1,200 European Jews streamed into the islands. They included a rabbi, doctors, chemists, and even a prominent conductor, Herbert Zipper, who went on to found the Manila Symphony.

This haven for Jews was closed in 1941, when Japan occupied the Philippines. Ironically, Japanese forces treated the Jewish refugees better than native Filipinos: seeing the Nazi stamps on Jewish refugees’ passports, it seems the Japanese occupation officials viewed the Jewish refugees as somehow German and thus quasi-allies, and did not intern all the refugees in camps. Despite this relative freedom, Jews suffered along with Filipinos during Japan’s brutal occupation: among the nearly one million Filipino civilians who died during World War Two, some were Jewish refugees.

When the Philippines gained independence in 1946, about 800 Jews called the new nation home. The Philippines was the only Asian country to vote for the establishment of the State of Israel in the UN in 1947. The small Jewish community stabilized at around 300 residents, mainly in Makati district of Manila. An influx of Syrian Jews helped revitalize the community there, and build a Jewish center, incorporating a synagogue, library, school, catering hall, and mikvah. Rabbi Eliyahu Azaria and his family moved from Chicago to Manila in 2004.

The town of Dothan, in Alabama, was incorporated in 1885, and Jewish immigrants soon settled in the town, a regional center of trade for the peanut industry. The first Jewish residents were Emanual and Emelia Crine, who immigrated to the US and moved to Dothan with their children in 1892. Other Jewish settlers soon followed and by 1929 the town was home to 14 Jewish families. That year, the Jews of Dothan built the town’s only synagogue, and a small Jewish population lived continued to live there: in 1980, 200 Jews lived in Dothan, out of a population of about 68,000.

In recent years, however, Dothan’s economy has declined. A general exodus of educated and young people has marked the town and the number of Jews has declined as well – to about 100 in the year 2000.

Local Jewish businessman Larry Blumberg can trace his family back to one of the founders of Dothan’s sole synagogue, and in 2008 he decided to do something to halt Dothan’s Jewish decline, pledging up to $1 million over ten years to help Jewish families move to Dothan. His gesture gained widespread media attention; people across the country flooded him with e-mails, thinking he was paying people millions of dollars to move. In reality, Mr. Blumberg’s offer was more modest. He was willing to help with moving and closing costs, offering to spend up to $50,000 per family, so long as families lived in Dothan for at least five years.

Though a few Jewish families have moved to Dothan in recent years, he’s never spent that much helping the newcomers with their moving and other fees. At least six Jewish families have moved to Dothan, some motivated in part by the publicity about the town that resulted from Mr. Blumberg’s offer. Jews who live in Dothan – both those born there and those who moved recently – face many challenges. “You really have to go out of your way to be a Jew,” here explains one community leader. There is no Jewish school in Dothan, and some families are concerned about the quality of local public schools. The first Jewish family to relocate with Mr. Blumberg’s assistance has since left. But the local synagogue has now doubled its weekly attendance, up to about thirty congregants on Shabbat, and has even opened a Jewish bowling league for the town’s approximately 140 Jews.

For years, Jews have enjoyed relative safety and acceptance in Finland. Ruled by Russia from 1809 to 1917, Finland was banned from housing Jews by the Czar, with one exception: in 1858, Czar Alexander II declared that Jews who’d served in the Russian army and were stationed in Finland could remain at the end of their army service. (Some 21 years before, Czar Nicholas I had declared that all Jewish boys 12 and over had to serve in the Russian army for 25 years. His aim was expressly to remove Jews from their homes and have them convert to Christianity. Yet those Jews who completed their service were allowed to stay in the location of their last posting – even if that region was officially forbidden to Jews.)

Because there were no Jewish women in Finland, these Jewish ex-soldiers were granted permission to ask matchmakers to find wives for them in the regions of Russia where Jews were allowed to live and bring them to Finland. Finland was so remote at that time, the only way into the country was by horse-drawn cart.

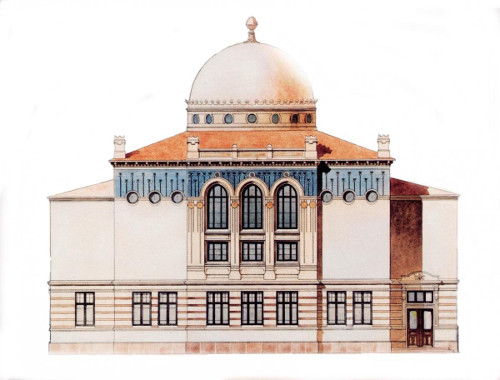

Sketch of Helsinki Synagogue in 1905

Sketch of Helsinki Synagogue in 1905

At first, local authorities restricted Jews to certain neighborhoods and specific trades. One acceptable profession was trading in old clothes, leading to Jewish businessmen founding Finland’s nascent textile industry.

As early as the 1830s, Jews had a special room in which to pray in Suomenlinna Fortress, the military base guarding Helsinki, which they shared with Russian Tatar soldiers who were Muslims. The first formal synagogue in Finland opened in 1870 in Helsinki, and the entire tiny Finnish Jewish community got a boost in 1909 when Russian Jews held a Zionist convention in Helsinki, which then had a more liberal attitude than Russia proper. That year, Finnish Jews dedicated a new synagogue in Helsinki, founded a Jewish literary and theatre club, and set up a thriving Jewish sports club which still exists today, the oldest continuously operated Maccabi club in the world.

Though allied with Nazi Germany during World War Two, eight Jews, instead of a much larger number, were deported to Nazi extermination camps. The fact that Finland protected its remaining Jews was due to Finland’s wartime leader, Marshal Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim. Though pressured by Germany to deport Finnish Jews, Mannerheim declared, “While Jews serve in my army I will not allow their deportation.”

300 Jews served in Finland’s army during the war. Eight were killed in battle, and three Finnish Jews were even awarded Iron Crosses for distinguished service (which they refused to wear). Finland’s army encouraged its Jewish soldiers to keep religious traditions. Jewish soldiers were granted leave on Shabbat and Jewish holidays, and even allowed a field synagogue in a tent along the Finnish-Soviet front, the only field synagogue in the entire German-allied army. The Jewish singer Sissy Wein was the most famous Finnish wartime entertainer. She entertained Finnish soldiers and refused to sing for German troops.

In 1948, 29 Finnish Jews went to fight in Israel’s War of Independence, and in the ensuing years, hundreds more Finnish Jews moved to the Jewish state. Finland today is home to 1,800 Jews (out of a total population of nearly 5.5 million). Finnish Jews live primarily in the capital Helsinki.

Each day, Jews around the world pray for the ingathering of Jewish exiles, beseeching the Almighty to “gather us together from the four corners of the earth”. May we soon merit this ingathering as Jews from these remote communities and others come together at last.