Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

8 min read

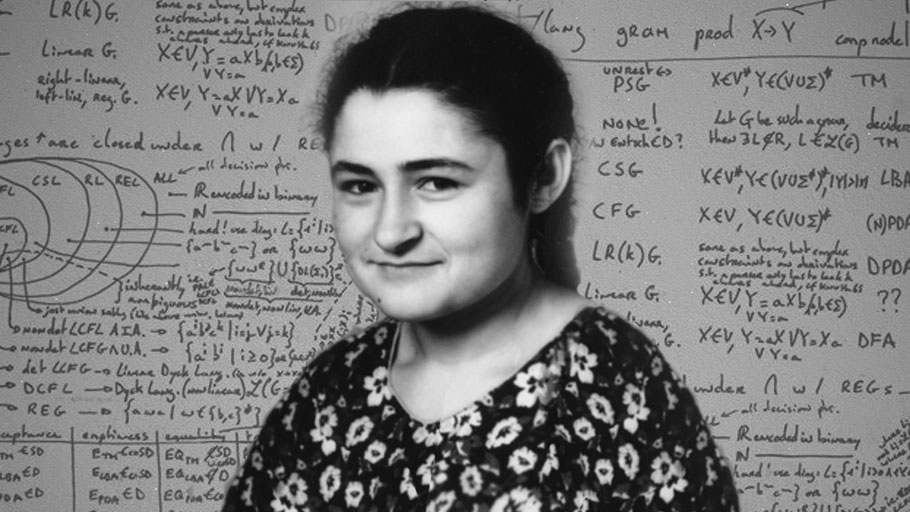

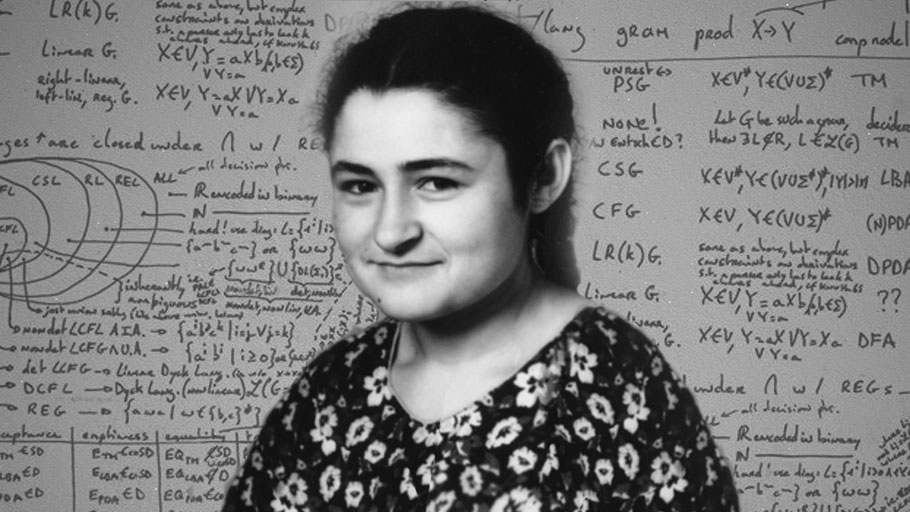

This Soviet mathematician founded an underground Jewish university and was likely assassinated by the KGB.

When Bella Abramovna, a young Jewish girl in the Soviet Union, was six, someone gave her a middle school math book. It was a huge volume with thousands of mathematical problems. Bella had solved them all within a month.

Bella lived with her mother in World War II-era Moscow. When she was just a child her father died fighting Hitler. Although Jewish education and religious rituals were banned in the Soviet Union, Bella grew up with a clear knowledge of her Jewish identity. When she was young, this meant speaking Yiddish with her family and later her husband and enjoying Jewish folk tunes. As Bella grew up, she was reminded of her Jewishness another way: through relentless prejudice and insults. Faced with crippling anti-Semitism, Bella decided to fight back, defying the Soviet Union’s repression of its Jews. She is one of Russian Jewry’s greatest heroes; her remarkable life deserves to be remembered.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the USSR’s Jews enjoyed a brief period of tolerance. It was during this time, in 1955, that Bella graduated high school and decided to study both math and music in university. A gifted mathematician and musician, Bella was accepted to the prestigious Mechanics and Mathematics Faculty of Moscow State University and the renowned Gnessinykh Musical Institute. She flourished, writing mathematical papers and emerging as a major thinker.

Bella enjoyed spending time with another Jewish student.

She met her husband Ilya Muchnik in 1960 when they both attended a seminar on the use of math in music. He later recalled that “we wandered through university corridors and discussed various possibilities of computer-generated music.” But it wasn’t Ilya’s intellectual prowess that drew Bella to him; she enjoyed the freedom that came from spending time with another Jewish student. “She suddenly understood that with me she could sit, listen and understand songs that were of great interest to her. Computer capabilities concerned her little. She just immersed herself in Jewish folk melody,” Ilya later recalled.

The two married the following year and settled in a heavily Jewish suburb outside of Moscow where all their neighbors spoke Yiddish like them. Bella worked on her Ph.D., publishing major breakthroughs in mathematics, and gave birth to her daughter Masha. Since there were no universities in their little suburb, a neighbor started teaching math to adults and Bella volunteered her time teaching. Once Masha was born, Bella turned her attention to tutoring young children in math instead, instructing them and also tutoring students for the entrance exams to the math departments in Russia’s prestigious universities.

This tutoring gave Bella a close up view of the doors that were fast slamming shut in the faces of the Soviet Union’s Jews. Schools like Moscow State University, where Bella had studied, were now only admitting a tiny handful of Jews. Jews who wished to study math and other subjects could only do so by applying to far-flung universities in Siberia; many gave up on their dreams of university-level study altogether.

An entire generation of Jewish students was being denied an education and any outlet for their intellectual potential.

Bella was friends with the Russian Jewish researcher Boris Kanevsky, who was documenting this discrimination. He described the plight of Russian Jewish students as “Intellectual Genocide”: an entire generation of Jewish students was being denied an education and any outlet for their intellectual potential.

In the 1970s, Bella and Ilya divorced and Bella and her daughter Masha moved into a small two-room apartment in Moscow. Faced with intense anti-Jewish discrimination all around her, Bella decided to do something to fight back. In 1978, she defied the Soviet authorities and announced to Moscow’s Jewish population that for the first time in a generation, Jewish children would be able to study high-level, college math. She opened a clandestine school in her home and proudly named it The Jewish People’s University.

It was an incredibly risky move. The Soviet authorities were ruthless in finding and punishing expressions of Jewish identity. Everything not controlled by the USSR was subject to sudden closure. Bella - as well as the Jewish students she instructed and the Jewish mathematicians she recruited to teach - were running a grave risk by studying outside of established universities.

It was an incredibly risky move. The Soviet authorities were ruthless in finding and punishing expressions of Jewish identity. Everything not controlled by the USSR was subject to sudden closure. Bella - as well as the Jewish students she instructed and the Jewish mathematicians she recruited to teach - were running a grave risk by studying outside of established universities.

Nevertheless, Jews flocked to her Jewish “university”.

The school opened in 1978 with 14 students and two lecturers. Within the first month, 30 students were attending classes. By the end of 1979, there were 110 students. Bella’s apartment was so tiny that the large chalkboard she bought for lessons had to be brought in through a window as it wouldn’t fit up the rickety staircase to her home. Bella quickly realized that if she was to teach all the Jewish students in Moscow who were hungry to learn, she’d have to expand into different premises. She arranged for classes to be given on the weekends in local universities when their lecture halls were empty. She personally would stop by the lectures, delivering handmade sandwiches to students and teachers.

Mathematician Andrei Zelevinsky taught at Bella’s “university” and he later recalled that “her warmth, kindness, and optimism immediately made one predisposed towards her and feel at ease with her. She showed motherly affection to the Jewish People’s University’s students and... evoked equally warm feelings in response. The organization of the Jewish People’s University demanded of her great courage and resolve...but there was no sign of self-importance or ‘showing off’.”

From the very beginning, the school was infiltrated by KGB agents.

For a few years, the Jewish People’s University flourished. Andrei Zeelvinsky reminisced: “Bella Abramovna’s…idea was humane and simple: attempt to at least partially restore fairness by offering students who were seriously interested in mathematics the possibility of receiving that fundamental mathematical education which the administrators of (Moscow State University, which severely limited the number of Jewish students admitted) deprived them.”

From the very beginning, the school was infiltrated by KGB agents. Bella gave stern instructions: only math could ever be discussed. She hoped that by avoiding any political conversation the authorities would leave her students and instructors alone. For five years the KGB waited, biding their time, allowing classes to continue. Hundreds of students passed through the “university” in that time. They received no official degrees, but an education that they never could have otherwise hoped for. For a generation of students, Bella’s Jewish People’s University was their only way to avoid the “intellectual genocide” that encompassed generations of Jewish students in the Soviet Union who were denied access to higher education.

In 1982, the KGB finally moved against the school. Two of the teacher’s Bella had recruited were arrested and accused of working against the state.

Soon, Bella herself was called into KGB headquarters. She gave a statement about her activities and was released. Over the next few days she was called into KGB headquarters again and again, charged with operating a Jewish People’s University outside of the law. Bella calmly explained her activities over and over, insisting that she was merely providing lessons for students and had done nothing wrong.

Her final interrogation came on September 24, 1982. After being released from KGB headquarters, Bella went to visit her mother. She left her mother’s Moscow apartment at around 11 o’clock at night and was walking home along a quiet street when a car passed her slowly by. It seemed that the people inside were staring at her, perhaps to identify her. Soon after that a speeding truck barreled down the quiet lane, hitting Bella. As she lay in a heap on the ground, another car drove up to her lifeless body, paused beside her, then drove off. Almost immediately, an ambulance came and took Bella to the morgue. She was 44 years old.

Bella’s death bore all the hallmarks of a KGB hit and nobody dared to speak at her funeral.

Bella was buried the next day. Her death bore all the hallmarks of a KGB hit and nobody dared to speak at her funeral. Bella Abramovna (she was also sometimes called Bella Subbotovskaya) was a famous mathematician, yet in death few people had the courage to speak up for her memory.

One mourner, Katherine Tylevich, recalled the fear that marked Bella’s burial: “Her funeral was a silent one. Amidst (Bella) Subbotovskaya’s students, colleagues, friends, family, and admirers, stood several unwelcome guests - several members of the KGB. Nobody volunteered to eulogize her; nobody made a sound except for her mother. The elderly Rebecca Yevseyevna (Bella’s mother) finally cried out: ‘Why won’t anybody pronounce one word!?’ Bella’s...husband quickly escorted the aged woman out of the funeral home.”

Bella Abramovna is today remembered as a pioneering mathematician for her work on logic and computational complexity theory. In addition to her research, she deserves to be remembered as a forgotten Jewish hero, too. Her Jewish People’s University enriched the lives of hundreds of Jewish students. Her example of courage and bravery in the face of anti-Semitism can inspire us all today.