Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

18 min read

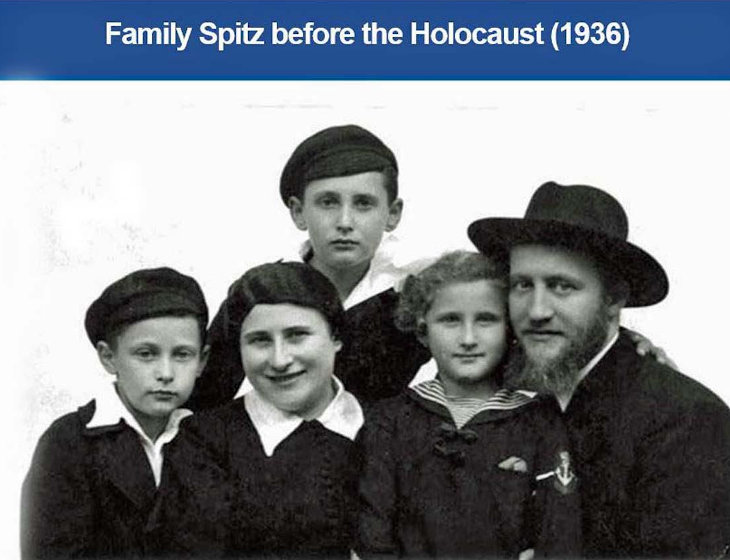

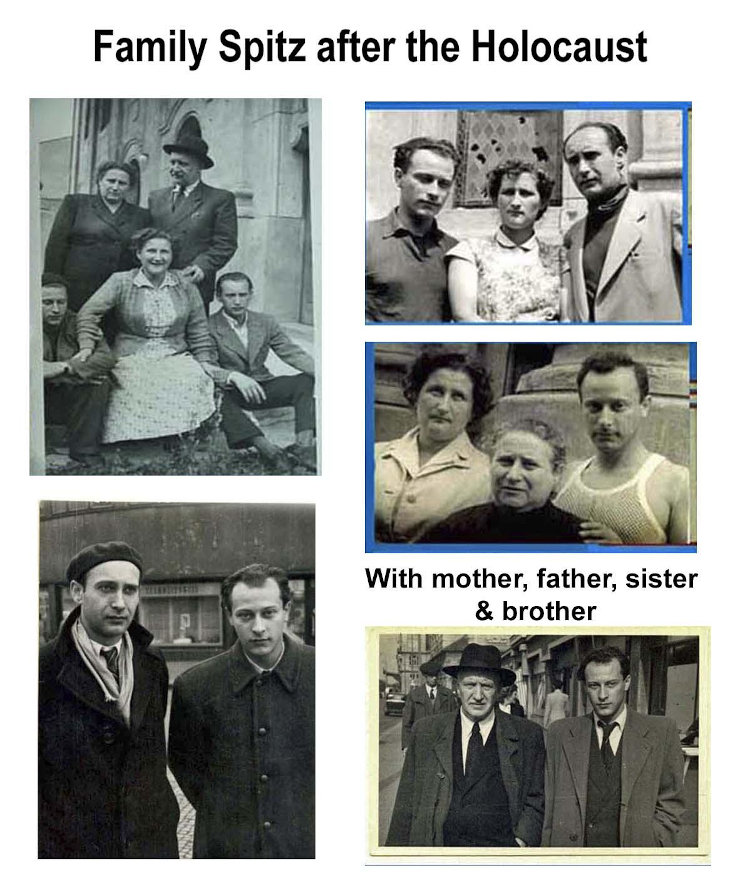

For 200 days Tibor Spitz and his family hid in a hole during the freezing winter to evade the Nazis.

Tibor Spitz, a retired chemical engineer turned renowned artist and educator, spoke to Aish.com about the extraordinary events of his life before, during and after the Holocaust.

Born in 1929, Tibor Spitz grew up in the small town of Dolny Kubin, nestled in a picturesque mountainous region of Orava, Slovakia, shouldering the country’s border with Poland. “It was a very beautiful place to grow up, but it wasn’t in my parents plans to live in Slovakia at all,” Spitz explains. “Several years earlier they had moved to the Land of Israel but had to return to Europe.”

Tibor Spitz, one year old, in 1930

Tibor Spitz, one year old, in 1930

Tibor’s parents Yosef Tzvi and Shoshana Spitz had realized their dream to settle in the Land of Israel in 1920, living in what was then the small town of Bnei Brak. “It was there that my oldest sister Esther Spitz was born, but she died at a young age from illness.” The couple’s fortunes continued to decline when Yosef Tzvi was shot by Arab marauders. Suffering from an infection to the wound, and with Shoshana pregnant, they were advised to return to Europe to receive medical care.

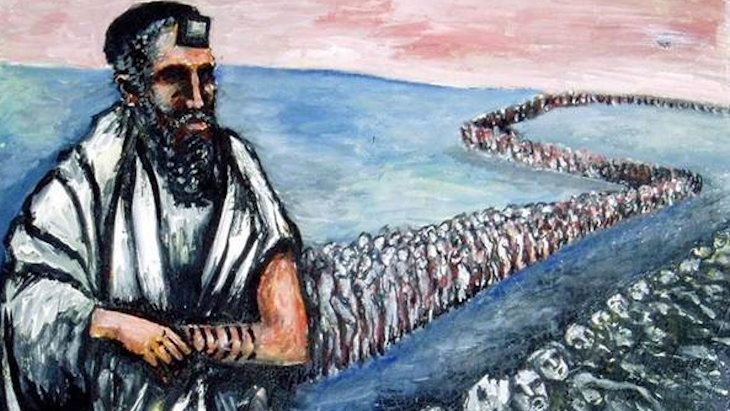

The Spitz family in 1936. Tibor is on the left

The Spitz family in 1936. Tibor is on the left

Back in Slovakia, the Spitz's had three children, Ernest, Chava and Tibor. “It was more or less a happy childhood. Living in the mountains made us tough, there was snow on the ground for around eight or ten months of the year and we became strong and healthy.”

“My father had the most beautiful voice. Before moving to Israel, he had trained as an opera singer in Vienna and he had mixed with so many well-known composers.“ In Slovakia he found work as a chazan. “My father was angelic person, and his voice was a healer.”

“Music was a basic part of my life, our home was filled with singing. My father often played music on a gramophone, and aside from leading services, he taught Hebrew and would give talks about living in the Land of Israel.” Tibor’s father also acted as the shochet (ritual slaughterer). “He did everything except circumcisions, and I was like the rabbi’s son.”

The Jewish community of Dolny Kubin numbered just 100 families. “We were not big enough to have a cheder, (Jewish school) so I along with the other Jewish children went to public school. Despite the small size of the community, it was rich in its diversity.”

Tibor was ten years old when the Nazis began their conquest of Europe.

In March 1939, Slovakia aligned itself as an ally to the Nazis, with Josef Tiso, a Catholic priest turned politician, introducing harsh anti-Jewish measures. (After the war in 1947, Tiso would be tried and executed for war crimes and crimes against humanity).

One day Tibor returned home with tears in his eyes. “As the only Jewish boy in a large elementary class, I asked my mother what I should do, as I was being cursed for being Jewish. She gave me this advice, ‘You better live the way that people would have reasons to envy you rather than feel sorry for you.’ It was then that I learned in any situation to try to remain a mensch, a decent human being.”

“In 1940, we were kicked out of public school and overnight my mother became a teacher to the town’s 24 Jewish children aged 6 to 16.”

Josef Tiso meeting Adolph Hitler. Slovakia aligned itself as a Nazi client state

Josef Tiso meeting Adolph Hitler. Slovakia aligned itself as a Nazi client state

In 1941, the Jews of Slovakia were forced to wear a star, and in the same year, the Slovak government negotiated with Nazi Germany for the mass deportation of Jews to German-occupied Poland. By 1942 deportations had begun. By the end of the war, around 69,000 of the country’s estimated 90,000 Jews had been murdered, although the deportations were staggered and typically shrouded in false promises.

“I used to ask myself: why they didn’t just deport all of the Jews straight away? But I realized, of course, that we would have tried to run away.”

“Tiso announced that the country would remain civilized, but each week or two, another measure was introduced against us. They took our property, musical equipment, eventually also our fur coats, jewelry and our money but life somehow just seemed to carry on.”

It was all a ruse; we were being sent to our deaths.

“When deportation orders were given, they told us to learn a manual trade for our new lives in the East, and they even provided workshops.” Tibor learned to be a bricklayer, while his father learned glass making. “It was all a ruse; we were being sent to our deaths. They turned up the heat of the water little by little until we were too weak and were trapped.”

After the deportations began, some Jews were left to run some confiscated businesses, pharmacies, essential services including the cemetery. “Part of my father’s duties had been to officiate at the Jewish funerals. My brother and I also helped with the manual cemetery work.” Yosef Zvi was told that his family would be deported on the last train.

“We didn’t trust the authorities and every time there was a deportation, we went into hiding.”

In 1943 Germans began to lose ground against the Russians on the Eastern front. “By that time, almost all Jews were gone and only some remained in either Slovak Labor camps or waiting in limbo, as we did.”

This situation continued until 1944 when part of the Slovak army along with many civilians joined partisans and started an uprising against the Slovak fascist government. The Red Army was already in neighboring Ukraine in the east and in Poland across the northern border, so the rebels expected a quick victory. But the Germans crushed the uprising and took over the entire territory of Slovakia.

Amid aerial bombardment and mortar fire, the Nazi invasion had seen many Slovaks leave the cities to seek refuge in the outlying villages. “One night, accompanied by my grandfather who had been staying with us, we collected our things and left, pretending to be refugees. It was chaos.

“The Germans put up posters – 'Come back to your homes, even Jews! You will have rights.'” The Spitz family was not convinced. “My parents said we would be crazy to go back to our homes.”

Briefly renting a room in a nearby village but knowing it still might take the Red Army months to break through on the Eastern front, Tibor’s brother Ernest came up with a plan.

“The Nazis were on every corner looking at documents. We were thinking of hiding under the ground in a forest for several months before my brother Ernest thought it over to the smallest detail. He said we needed to find a stream that would give us a water supply, in a steep valley far enough off the beaten track that no one would pass through.”

Ernest’s plan was to cut a triangle out of the slope near to the floor of the valley, which would provide the family with cover from the rain and shade from the sun.

“With neither pen, nor ink or paper to draw on, he used charcoal from the brick stove to draw a plan on the wall of the apartment we were hiding in, and we tried to remember every detail.”

After Ernest had located a steep valley that closely matched their needs, they began to prepare for their escape.

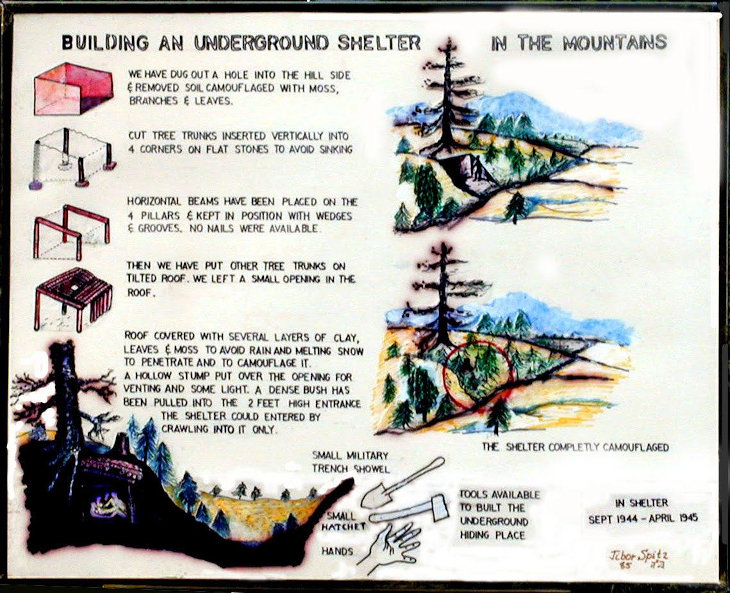

“During the day we would stay in the village, pretending to be war refugees helping the villagers with their harvest, but at nights we would build our shelter. We had neither tools, nor nails or ropes. Just a small military trench shovel we found, a small hatchet, and our bare hands.

“It was extremely difficult to dig the ground in a pristine forest, pull out boulders and rocks, cut roots, and move the dirt. Our hands were bloody. To make a hole to squeeze six people into the side of a steep hill took days. We improvised, used fallen tree trunks and branches and then camouflaged the area so that nothing would reveal any human presence.”

After completing the shelter and camouflaging the area the family disappeared into the forest.

Illustration by Spitz of how the family built their forest hideout

Illustration by Spitz of how the family built their forest hideout

“Not all Slovaks were fanatical believers in the Nazi victory, and the German Army was close to collapse, so it did not even cross our minds that we would have to spent such a long time in the snow-covered mountain. Also nobody forecast that 1944 would be the coldest winter of the century.

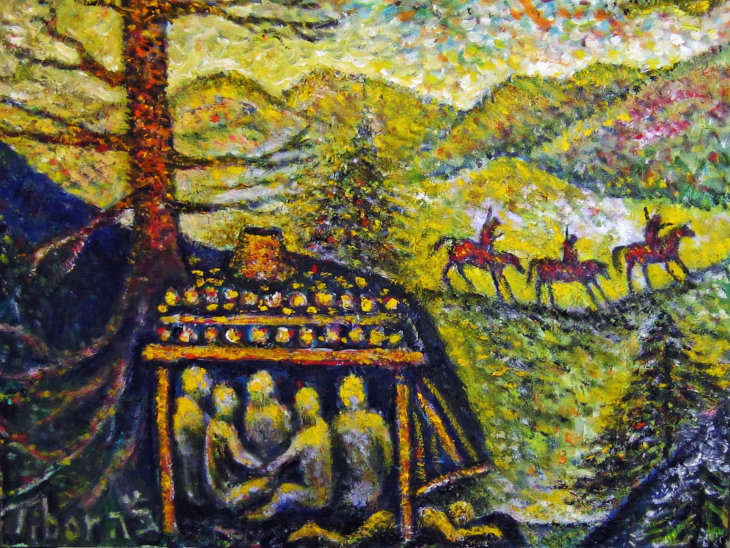

“We hid for 200 days, and every day was the longest I have ever experienced. As patrols on horseback and foot searched the forests, each day could have been our last.

“Under the ground, we didn’t feel the cold so much, and we also had three layers of clothes. I vividly remember that the hole was smaller than we needed and we could not stretch or lie out. We were squeezed into uncomfortable positions.

A painting by Spitz of the family’s underground hideout. Patrols were a common threat

A painting by Spitz of the family’s underground hideout. Patrols were a common threat

“We lived like animals, like foxes, instinctively, surviving from one minute to the next. We ate berries, we knew the mushrooms that we could eat, and sucked the water from the snow and ice to stay alive. The forests and the wild nature felt like friends helping us to hide from the human predators and murderers.

“When I would go to find food, I would fill in my footprints with snow to prevent anyone discovering our whereabouts.”

“It was just a biological level of survival. That’s all.” Spitz says, “On the most basic level that you could imagine, nothing else mattered.”

In February 1944, just over two months into hiding, Ukrainian partisans assisting the Red Army and operating in the forest discovered the Spitz family.

“They lined us up, one of them guarded us while the other went through our things. My mother said we should pray, but my father just wanted it to be over with, they began arguing. ‘We are not your enemies,' my mother pleaded with them. ‘It’s not worth it, Hitler wants to kill us all,' my father interrupted her. Meanwhile, the soldiers began laughing watching them argue it out.”

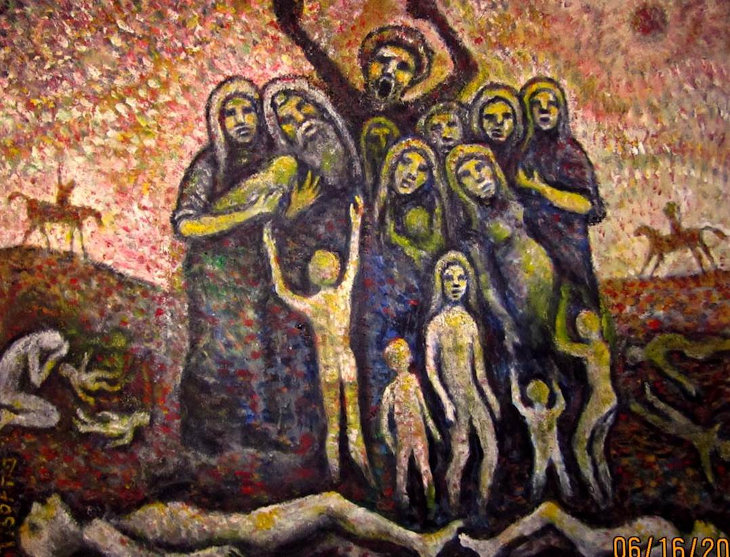

The end of family, by Spitz

The end of family, by Spitz

Amid the scene, Tibor hedged his bets and ran away, returning hours later after he hadn’t heard any shots.

“It turned out that they had been under strict orders not to kill civilians, but they had taken all of our clothes and the primitive food supply we had. It was a miracle to not be killed, but that winter was the coldest of the century and it was practically a death sentence.”

That night, the family wondered whether they should risk going to a nearby village to ask for help, or stay where they were and freeze or starve to death. “The SS Gestapo was absolutely desperate to kill us; we had witnessed enough of their crimes to know how much money they put on Jewish heads.”

“As we were freezing, something incredible happened to us that I look at as a miracle. We were so cold, and from nowhere, there erupted a warm spring of water with a strong smell of sulphur. It warmed our tiny hole in the valley. It was such a healer and raised our spirits.”

With renewed hope, Tibor’s mother took the risk of asking for help. “These villages were stricken with poverty. Eventually she found partisans who also had very little but they were sympathetic to our family’s needs."

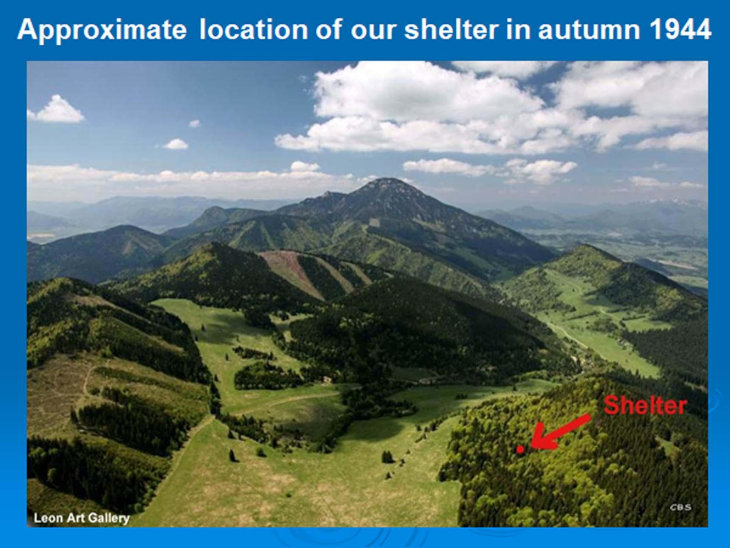

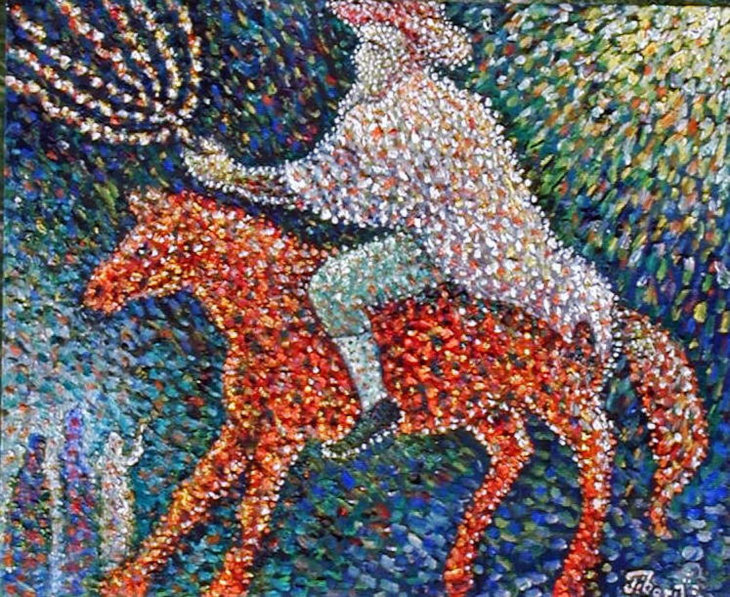

Menorah, by Tibor Spitz, a message of hope

Menorah, by Tibor Spitz, a message of hope

In April 1945 news of the end of the war reached the Spitz family hiding in the forest. Tibor was 14 years old. “One day peasants came through the forests calling out, ‘If you are alive, come out.’ This was our liberation.”

“At first, we went back to my grandfather’s home where he and our grandmother had raised their seven children.” The grandfather had suffered from the physical and emotional strain of the war. “Aside from us, all of his other children and grandchildren were wiped out. He was broken by the loss, and lasted just three months before he died.”

In July, 1945 the family returned to Dolny Kubin. “People looked at us like we were ghosts, and were even coming up to us and touching us. Because of all that had happened, we couldn’t have been real people.

“Life was so unpleasant, yet we tried to continue our lives. At the end of that summer, in September we went back to school. I had lost a year of studies and it was not easy.”

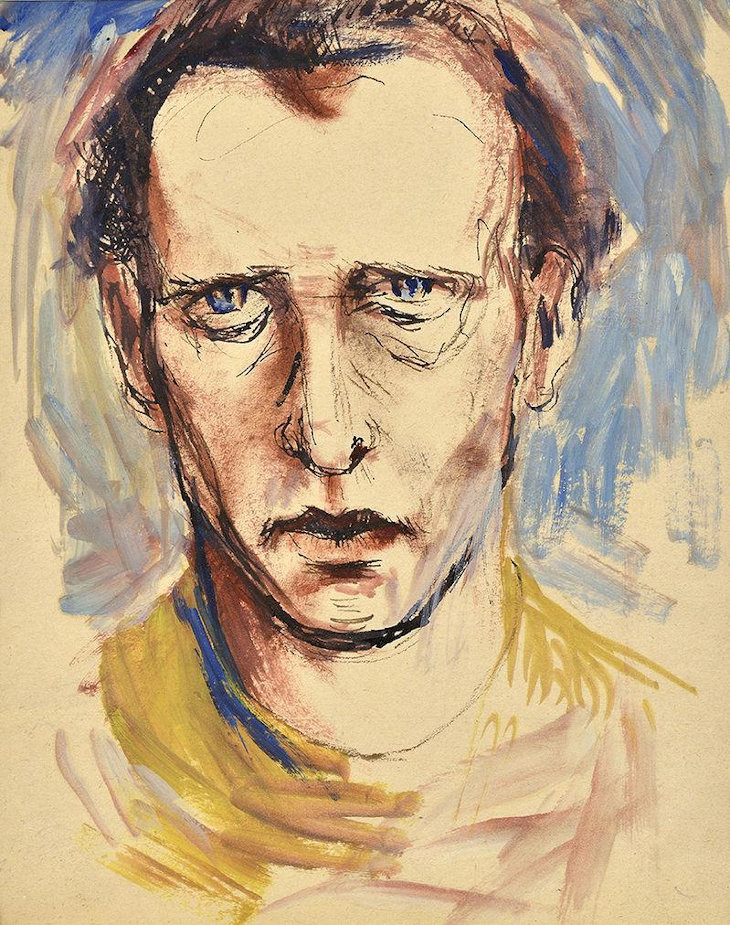

Later, the Spitz family moved to another town, Liptovsky Mikulas, 50km away, where Yosef Zvi once again took on the role of rabbi and cantor for the Jews that remained there. Later Tibor and Ernest headed to Prague to complete high school and then university. “I went on to study chemistry while my brother studied art.

“Prague was the best place to be as a chemistry student.” He scored the highest grades in his school. Meanwhile, Ernest was making a reputation as a talented artist.

“He was outspoken in fighting against the communist regime for artists’ expression. He opened a gallery, and shared messages through his paintings and murals promoting human rights.” Sadly, he died a young man aged 33. “I don’t have the proof, but I think the authorities were behind his death.”

Self portrait by Ernest Spitz, 1955, five years before his death aged 33

Self portrait by Ernest Spitz, 1955, five years before his death aged 33

“When I look back now, what motivates me to tell my story is my forced silence while living in communist Czechoslovakia. Judaism was considered a hostile, subversive ideology and Jewish suffering and the subject of the Holocaust became practically forbidden in politics, cultural life, art and literature alike.

“There was no outlet for either healing or reducing the pain. To the contrary, we were constantly reminded and suspected of having connections to democratic Israel that was oriented towards the West and became an adversary to the USSR. Religious institutions were persecuted but the accumulated traditional hatred and hostility against the Jewish religion became specifically intense. Judaism, with its wisdom and promotion of freedom, particularly irritated the dictators who considered the Jews to be subversive enemies."

During his time in Prague, Tibor’s father also passed away. “He was taken to hospital with something trivial and never came out. He was not even 60.”

His sister Chava cared for their mother who died in Slovakia in 1986. "Chava later moved to Kfar Saba in Israel and was married and had children but died just ten years later.”

In 1967, aged 38, after graduating with a PhD in chemistry, Spitz was encouraged to meet Noemi, a daughter of the head of the Jewish community of Bratislava, and also a survivor of the Holocaust.

“I was raised deeply as a Jew, and so after the war it was absolutely essential to me that I could only marry a Jew. I was a good catch,” he laughs. “As a husband, I had everything a girl could imagine, I was educated, and had job prospects, but for years I resisted marriage as I felt a built-in conflict. Life was still far from normal, where a person could just walk up to you and call you a dirty Jew.”

Tibor and Noemi met and their second meeting was their wedding – a private ceremony in Prague City Hall.

“God gives us the strength to survive.” Tibor says. “Survival is not only about dodging the bullets, God gave us a ‘seichel’ a brain, and we are given all the tools we need.”

Accepting a work contract in Cuba, Tibor and Noemi left Prague. Nine months later, they made a successful attempt to escape from a refueling Cuban airplane and became political refugees living in Canada. “At home the courts sentenced us to 15 years in prison.”

After nine years in Canada, they settled in the US in Kingston, where Tibor worked for a company pioneering magnetic recording heads.

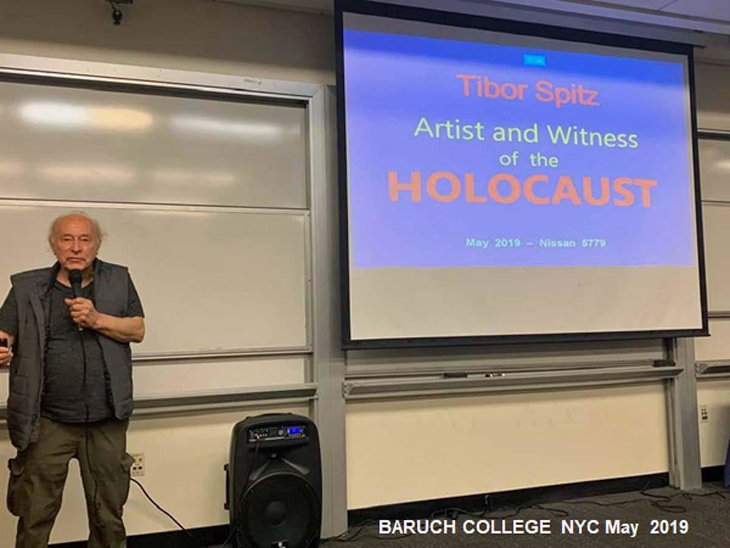

Over the years, Spitz has taken a prominent role in Holocaust education and is a regular speaker at universities, high schools and embassies in the US. Last year, he gave 26 lectures alone.

Delivering a lecture in May 2019 to Baruch College, NYC

Delivering a lecture in May 2019 to Baruch College, NYC

“Jewish collective ignorance, disbelief in unlimited cruelty and lack of unity before and during the Nazi era cost us the lives of a third of all Jews on this planet. No other nation or country would have survived such impact, yet three years after it ended, the Jews proclaimed the existence of the State of Israel on the territory of their ancestors.

“I have visited Israel many times. It is a 2,000-year-old dream. It is a miracle and we live in a generation when it is happening before our eyes. We need to be proud of who we are.

“To be a Jew, for me, is to live with an uncompromising moral fight for justice. I was raised to be proud as a Jew and I still feel that. Every holiday is my favorite holiday, they each teach such important lessons with unprecedented wisdom. But now, I think to myself, I am alive and I see every day as a holiday.”

World leaders have also been guests at his lectures, especially from Slovakia of whom he has been invited to meet successive presidents.

“I stress the importance of seeing world events truthfully without adjusting them to be either more pleasant or harmless, to learn from our mistakes and the mistakes of others and to eliminate fear as an emotion.

“We should also remember that Western civilizations based their values on Jewish Scriptures connected to pursuing peace, cooperation and tolerance, including the Jewish principle 'Do not do to others you do not want done to you.'”

Together with his wife, Noemi and former Slovakian President Andrej Kiska

Together with his wife, Noemi and former Slovakian President Andrej Kiska

In 2002, Tibor was invited by a film crew to try to relocate their hideout. “An old woman who remembered our family from the war times explained that for many years villagers had visited our hiding place to commemorate the superhuman endurance of a Jewish family hiding in their forest.

“After more than seven decades it was not easy to find the remnants of an underground place covering just a few square yards. Topography of the area had changed significantly as the forest wood was harvested and the areas covered by trees have significantly changed.

At the site in the forest of what remains of the hideout

At the site in the forest of what remains of the hideout

“With the help of villagers who remembered the area before the deforestation, we were able to locate the remnants of the collapsed shelter. Now it is marked for the visitors."

Five years ago, an annual ‘Peace March’ began, with hundreds of people walking from the nearest village to the hideout, with Tibor and his wife participating as an eyewitness giving public lectures and interviews for local and national TV and radio.

“Revisiting brought memories of the terrible times and so many victims, too many of them children, my cousins, and schoolmates – one of them shot dead while also hiding in the forest. I also felt celebration for freedom and life as well. I was filled with an awareness of breathing, feeling, loving, and the ability to perceive colors, shapes and sounds to listen to music and human speech. Not to be hungry to the level of counting the last drop of energy before your body shuts down and to be in the presence of people you do not have to be afraid of.”

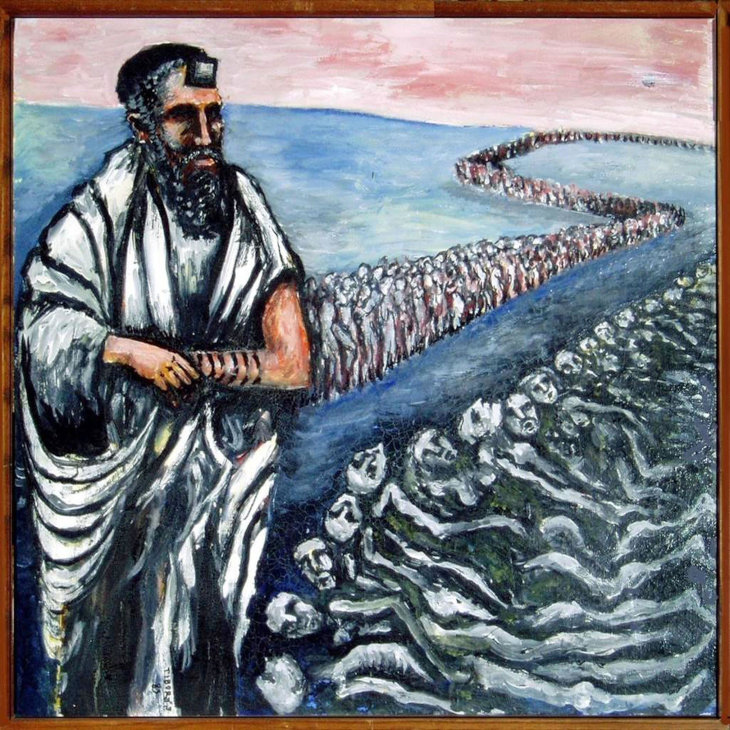

Over the last few decades, Tibor Spitz’s artwork has been displayed in the US, Canada and Europe. His artwork shares a variety of themes, not only the Holocaust, but also Kabballah, Jewish heritage and identity. He paints, sculpts and works with ceramic, wood among other artforms.

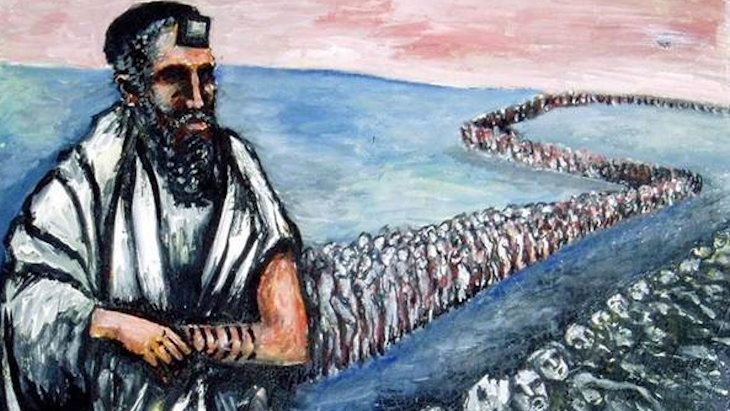

The March to Eternity, artwork by Tibor Spitz

The March to Eternity, artwork by Tibor Spitz

“In 2002 I received an offer to exhibit my Holocaust paintings in Bratislava, Slovakia. Slovak President Schuster sponsored the event, and arrived there personally together with other government representatives.”

Several additional exhibitions of Tibor’s artwork have also been held in the country since. The last was held in August 2019 in Dolny Kubin on the occasion of Tibor’s 90th birthday.

The Spitz’s living room is adorned with 50 of his own works. One of his latest creations was a wood carving shaped into a horse with a rider, in honor of a local bar mitzvah boy. “This piece of wood had a hole in it, he says. I found a good use for it.” He adds, showing how it became the horse's eye. “I say, don’t cry over spilt milk, you can turn everything in life into a positive. You have to stay positive; if not, you live your life in disharmony.”