Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

Some lesser-known facts about Jewish individuals and communities in Early America.

American Jewish history goes back centuries. Here are some lesser-known facts about Jewish individuals and communities in Early America.

With the advent of the Spanish Inquisition, one Jew by the name of Yosef ben HaLevi Halvri hid his Jewishness and changed his name to Luis de Torres – and, like many Spanish Jews, sought a way to escape. His chance came on August 3, 1492, three days after the royal edict went into effect banning all Jews from living in Spain on pain of death. de Torres – along with other secret Jews – set sail with Christopher Columbus, trying to explore a sea passage to Asia. Fluent in Portuguese, Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic, de Tores hoped to communicate with Jewish and Arab traders.

Instead, the crew landed in the Caribbean. On the island of Cuba, Luis de Torres and another crewman went ashore to explore and came back with reports of finding a Native American village and observing a curious custom there: men rolled up plant leaves called “tabaco”, lit them an on fire, and inhaled the smoke, de Torres documented.

When Columbus and his crew departed, Luis de Torres stayed behind – one of 39 men who volunteered to settle in the New World. Returning to the island in 1493, Columbus found the settlement destroyed and the men massacred. In 1972, de Torres was finally memorialized when the Luis de Torres Synagogue opened in the Bahamas, recalling the area’s first Jewish resident.

The first Jewish families to arrive in the colony of New Amsterdam disembarked from the Ste. Catherine in early September 1654. These six men, seven women and ten children – Dutch citizens – were fleeing Brazil, an embattled Dutch colony that was increasingly being overtaken by Portugal – and coming under the Portuguese Inquisition, which promised torture or death to Jews living in its territories.

Governor Peter Stuyvesant was furious. The new colonists were “enemies and blasphemers” he wrote to the Dutch West India Company, part of a “deceitful race” and would “infect and trouble this new colony”. The governor demanded they leave forthwith, on the next outbound vessel.

But these bedraggled, penniless newcomers refused to be cowed. They too wrote urgent letters to the authorities in Holland, pointing out that they were “confirmed burghers” of the Netherlands, just like “all the other inhabitants of these lands” and demanded their right to live in the colony. For over a year, these 23 Jews and Governor Stuyvesant waited urgently for a reply that would determine the future of Jewish settlement in North America.

Finally, in April 1655, a letter came from Amsterdam: forbidding Jews from the colony was “unreasonable and unfair”. Conditions were put upon the Jews that weren’t demanded of other colonists – they were barred from ever receiving charity from non-Jews – but their safety was ensured. These Jewish colonists established Shearith Israel – the first synagogue in Colonial America – and the oldest surviving congregation in the United States.

Francis Salvador, a prominent member of London’s Jewish community, moved to the colony of South Carolina in 1773 at the age of 26, and quickly threw himself into the cause of American Independence. He ran for a seat in the colony’s revolutionary Provincial Congress and became the first Jew to hold an elective office of that level in the colonies.

At the Provincial Congress’ meeting in November 1775, Salvador was among those urging the gathering to instruct South Carolina’s delegation to the Constitutional Congress in Philadelphia to vote for independence.

Salvador died a military hero, just days before the independence of his adopted homeland. Part of a special commission to maintain peace with Cherokee tribes who were hostile to westward expansion, Salvador raised the alarm on July 1, 1776, when Cherokee troops attacked frontier settlements. He rode 30 miles to the nearest militia and then returned to the site of the battles with the soldiers, ready to defend his fledgling state. In the midst of battle, he was shot and scalped, the first Jewish American to fall in battle from South Carolina.

With his buckskin breeches and raccoon-fur cap, Joseph Simon might have looked like any other pioneering fur trader in the American frontier of the 1700s. Arriving in the Colonies in 1740, German-born Simon moved to the pioneer village Hickory Town (today Lancaster, Pennsylvania). There, he made regular forays across the Appalachians, trading with Native Americans in furs and other goods.

Unlike the other traders, though, Simon never ate meat: at a time when frontiersmen regularly trapped animals for food, he subsisted on a diet of fruits, vegetables, grains and hard boiled eggs. In fact, though he lived in an area where Jews were almost completely unknown for many years, Joseph Simon seems to have maintained an Orthodox lifestyle. He was known for never doing business on Shabbat, and even built an Ark in his home housing a Torah scroll he likely brought to America with him from Europe. Decorating the Ark in the eastern wall of his parlor was the Hebrew inscription “Know Before Whom You Stand”. Early morning visitors to his home reported seeing Simon praying Shacharit, the Morning Service, with a white tallit over his head.

A few years later, a handful of Sephardi Jews made their way to Hickory Town and Simon at last had a minyan, or quorum of ten men, with whom to pray. One newcomer, Nunes Henriques, was even a shochet, or ritual slaughterer, so at last the fledgling Jewish community could enjoy kosher meat. A deed from 1747 shows the first joint action of the Hickory Town Jewish community: Simon and Henriques together bought a plot of land on which to bury a member of the new community who had passed away: that frontier area’s very first Jewish cemetery.

The Charleston, South Carolina, militia that was commanded by Captain Richard Lushington was different from other militias that fought for America’s independence. Locally raised, militias often drew members from close-knit communities, and the company that would soon be known throughout the South as the “Jew Company” of Charleston was recruited from King Street, the epicenter of colonial Charleston’s Jewish community.

The company conducted itself with distinction, fighting to recapture Savannah, Georgia from British troops. One Jewish fighter, Joseph Solomon, was killed at the battle of Beaufort in 1779 and another, David Cardozo, was captured by British forces.

It’s not recorded whether any of the Charleston Jews who defended Savannah had a chance to visit with the town’s small Jewish community, but if they did, they would have found a welcome reception. Jews first settled in Savannah in the 1730s, and in 1735 dedicated Kahal Kodesh Mickve Israel, Savannah’s oldest Jewish congregation – and the second synagogue to be established in Colonial America.

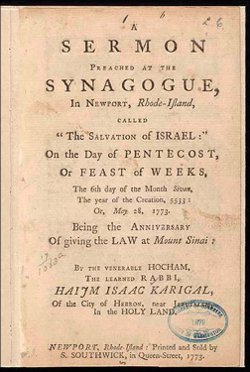

Newport, in Rhode Island, was an early center of Jewish life in the Colonies: Jews from Holland, Portugal and Spain – many of whom had hidden their Jewish identity for generations in fear of the Inquisition – settled in the town as early as 1658. By 1712, the street where many Jewish families lived was known as “Jew Street” and in 1763, the community dedicated the Touro Synagogue, the Colonies’ third congregation and today, the oldest continuously-used synagogue building.

This historic structure has one interesting feature, reflecting the fear of the many crypto-Jews who helped found the congregation: a secret trap door is built under the Bimah, the platform where the Torah is read, ready to shelter Jews who feared reprisals for practicing their faith.

This historic structure has one interesting feature, reflecting the fear of the many crypto-Jews who helped found the congregation: a secret trap door is built under the Bimah, the platform where the Torah is read, ready to shelter Jews who feared reprisals for practicing their faith.

While the trap door and secret hiding space was never required by Jews in Rhode Island’s tolerant atmosphere, the hiding area under the Bimah was used hundreds of years later as a shelter for escaped slaves along the Underground Railroad.

One of the greatest American patriots was Chaim Salomon, a Polish-born Jew who immigrated to colonial New York and worked as a financial broker. Arrested by the British in 1776 for being a patriot spy, Salomon was pardoned on condition that he work for the British as a translator for the German mercenary troops they employed. Salomon became a double agent: working for the British by day, but helping Patriot prisoners escape and encouraging German soldiers to desert.

He was arrested again in 1778 and sentenced to death, but managed to escape to Philadelphia, where he became a financial broker to the French consul and paymaster to French troops fighting on the Patriot side – and a pillar of Philadelphia’s Jewish community. When the Bank of North America was established to raise money for American Independence, Salomon was a major backer, extending interest-free personal loans to many of the leaders of the Revolution, including James Madison, and brokering bills of exchange from American, Dutch and French backers for the fledgling American government.

In 1781, funds – and morale – among American troops were at their lowest. Unable to afford provisions, uniforms, or arms, George Washington’s troops were dangerously close to mutiny, and Washington doubted his ability to continue fighting. “Send for Haym Salomon” General Washington asked an aid – and once again, Salomon came to the rescue, raising over $20,000 at short notice to fund further military actions. His funding enabled the Yorktown Campaign which helped turn the tide of the war and ensure American success.

Salomon never asked for compensation and was never repaid, dying in poverty in 1785, at the age of 44, of tuberculosis he’d contracted in prison. Efforts by his descendants to obtain compensation from the new American Government that Salomon has done so much to support were unsuccessful.