Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

Jewish Geography

Jewish Geography

11 min read

Jews lived in thriving Kurdish communities for thousands of years.

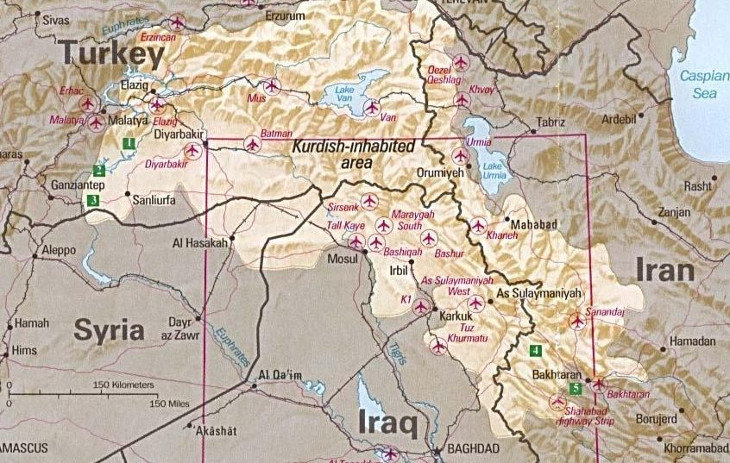

Kurds are one of the oldest and largest ethnic groups in the Middle East. For hundreds of years they have called an area encompassing parts of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Armenia home. Promised an independent homeland by Western powers in 1920, they have never achieved a state of their own. Instead, distinctive Kurdish communities have maintained Kurdish culture and language in a number of countries, often in the face of hatred and violence from neighboring ethnic groups and central governments.

The modern-day region of Kurdistan.

The modern-day region of Kurdistan.

For much of Kurdish history, Jews were an integral part of life. Persecuted in much of the Middle East, Jewish towns and villages flourished in Kurdish lands. Here are ten little known facts about Jews from Kurdish lands in the past and today.

Many Jewish communities in Kurdish lands claim they have lived there for over 2,500 years, ever since the Jews of the northern kingdom of Israel were sent into exile there. The Tanach records that in the 8th Century BCE, “Shalmaneser king of Assyria went up against” the Jewish King Hoshea, invading Jewish lands and laying siege to cities and towns. Eventually, “the king of Assyria captured Samaria and exiled Israel to Assyria. He settled them in Halah, in Habor, by the Gozan River, and in the cities of Media” (Kings II, 17:1-6). These sites listed are within the Kurdish regions of Iran and Central Asia.

For generations, the Jews in Kurdish areas lived in relative isolation. Many worked as farmers and their insular communities developed distinct customs, including marrying at a very young age and praying at the graves of Jewish prophets. The medieval Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited Kurdish areas in 1170 CE and encountered over a hundred Jewish communities in Kurdish lands. One of the largest was Amadiya in current-day Iraq, where he recorded that the Jewish community numbered about 25,000. Though the largest community of non-Jewish Kurds is found in present-day Turkey, Kurdish Jews lived primarily further east, in modern Iraq.

The Babylonian Talmud is written in Aramaic, a language that uses Hebrew letters and is closely related to Hebrew, but with some key differences. For generations, Jews living in Kurdish lands maintained Aramaic as their everyday spoken language. They adopted some words from Turkish, Persian, Kurdish, Arabic and Hebrew, but in general spoke an Aramaic very similar to their ancestors in Talmudic times.

Kurdish Jews called their language “Lishna Yahudiya”, meaning the “Jewish Language” or “Lashon Ha’Targum”, meaning “Language of the Translation”, presumably referring to translations of the Torah, or “Lashon HaGalut”, meaning “Language of Exile” (from the land of Israel). Local Arabs called the Jews’ language Jabali, meaning “from the mountains”, referring to where some Jews in Kurdish lands lived.

In the First Century CE, the kingdom of Adiabene in Iran became a loyal part of the Jewish community after the local monarch’s wife, Queen Helene, converted to Judaism and encouraged her subjects to do the same. Kurdish Jews still recall the kingdom of Adiabene in what is today Kurdish lands as part of their unique heritage.

Queen Helene’s remarkable journey is recorded in the writings by the Roman Jewish historian Josephus and in the Talmud (Gittin 60a). Queen Helene and her husband King Monobaz of Adiabene regularly encountered Jewish merchants passing through their lands. Queen Helene was so impressed with Jewish life that she hired a teacher to tutor her in Judaism.

An immigrant from Kurdistan arrives in Israel with her son, 1951. (Photo: Israel Government Press Office)

An immigrant from Kurdistan arrives in Israel with her son, 1951. (Photo: Israel Government Press Office)

After King Monobaz died, his son Izates took his place on the throne. Like his mother Queen Helene, Izates was also interested in Judaism and the pair learned all they could, first from a Jewish trader named Chananyah, then from a rabbi named Rabbi Eleazar of Galilee. Eventually, the royal family converted to Judaism and encouraged their subjects to do the same. They sent many gifts to the land of Israel, including beautiful golden candelabras and goblets for the Temple in Jerusalem, and shipments of emergency food during a famine. When Roman forces battled Jews, Queen Helene sent soldiers to help their Jewish brethren.

The Jewish kingdom of Adiabene lasted until 115 CE, when Roman forces crushed its leaders, but Kurdish Jews continue to regard its descendants as part of their Jewish community.

One of the greatest Jewish scholars from Kurdish lands was a woman named Asnat Barazani, who led a respected yeshiva in the town of Mosul, in present day Iraq, in the 1600s. Asnat’s father Rabbi Shmuel ben Netanel Ha-Levi of Kurdistan built the school in Mosul to train a new generation of Jewish scholars – including his daughter. Perhaps because he had no sons, Rabbi Shmuel lavished care and attention on his daughter’s studies.

In a letter, Asnat described the intense education of her childhood: “I never left the entrance to my house or went outside, I was like a princess of Israel… I grew up on the laps of scholars, anchored to my father of blessed memory.”

Asnat married a fellow scholar, Rabbi Jacob Mizrahi, and had an unusual clause in her marriage contract: Asnat was never to be expected to perform any housework so that she could devote herself entirely to learning Torah.

After her husband died, Aseat continued to run the family yeshiva, which by then was plagued by financial problems. Asnat wrote a famous prayer, Ga’agua L’Zion, or “Longing for Zion”, which allowed many Jews to put their deepest hopes and desires into words of prayer.

In the 12th Century CE, some Jews fled violent Crusaders in Syria and the Land of Israel, finding refuge among the Jewish communities of Kurdistan. In the mid-13th century CE, Iraqi Jews fled from major Jewish centers like Baghdad as Mongol captured those areas; many moved north and west into Kurdish areas, joining the vibrant Jewish communities there.

As Jews poured from the land of Israel into Kurdish areas, David Alroy, an infamous Kurdish Jewish figure, arose. In the 12th century in the city of Amadiya, he raised a Jewish army and prepared to march to Jerusalem and liberate the city from the Crusaders. Before his Jewish warriors could depart on this mission, David Alroy was killed.

Accounts vary. The Jewish explorer Benjamin of Tudela wrote that he was murdered by the local sultan after encouraging Jews to rise up against their rulers. Some accounts maintain that Alroy was killed in his sleep by his father-in-law. After his death, some Jews falsely revered Alroy as the Messiah, even though his grand plan to come to the aid of Jerusalem’s Jews had utterly failed.

Kurdish Jews particularly revere the Jewish prophet Nahum who wrote about the end of the Assyrian Empire and its capital city Nineveh. Each year during the holiday Shavuot, Jews travelled to Nahum’s tomb, in modern-day Iraq, staging elaborate holiday celebrations there.

Nahum's Tomb

Nahum's Tomb

Local Jews described a major renovation of the tomb in 1796, paid for by wealthy Jews from Iraq and India. The tomb was owned and operated by the local Jewish community, and was a sumptuous center of gathering. A visitor during World War I described its splendor: the floors were covered with beautiful Persian rugs, and hundreds of notes with Hebrew prayers on them covered the walls. The building also housed lodging rooms where visitors could stay and pray.

After Kurdish Jews fled their homes for Israel in the 1950s, the Tomb of Nahum was cared for by a local Chaldean Christian family. They were not able to keep it up and today the building is largely in ruins. The tomb is located in a Christian village about 30 miles north of the Iraqi city of Mosul, which was the site of many bloody battles recently between ISIS fighters and local Kurds. Kurdish Peshmerga forces protected Nahum’s tomb throughout the fighting, preventing ISIS forces from destroying it completely.

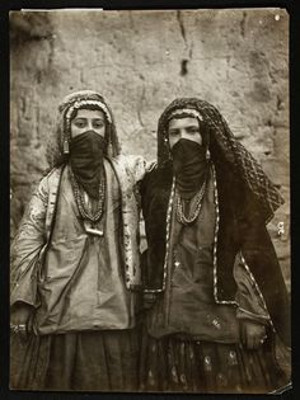

Kurdish Jews in Rawanduz, northern Iraq, 1905

Kurdish Jews in Rawanduz, northern Iraq, 1905

Jews from Kurdish lands were intensely Zionist; generations longed to return to the land of Israel from where their ancestors originally came. Jews in Kurdish areas had contact with travelers and rabbis from the land of Israel, and learned Torah and heard news from them. In the 16th century, Kurdish Jews began moving to the land of Israel, settling in the city of Safed. Thousands more moved to Israel during the 1920s and 1930s.

Despite its vibrancy, life was hard for Jewish in Kurdish lands. Tribal squirmishes posed danger to many groups, including Jews, and the area’s harsh landscape made it difficult to farm and thrive. After 1948 when the State of Israel was established, life became even more difficult for Kurdish Jews, most of whom lived in present-day Iraq. Iraqi’s government passed a series of harsh decrees against Iraqi Jews, seizing their assets and stripping many Jews of citizenship.

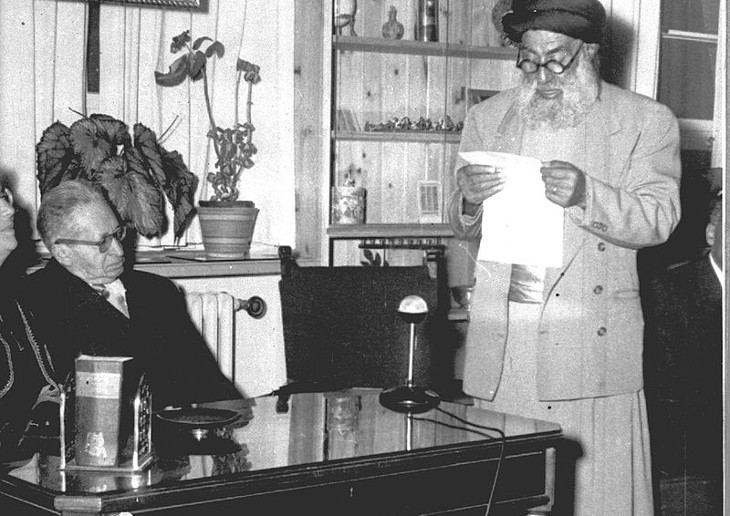

Rabbi Moshe Gabbai, head of the Jews of Zacho Iraq who immigrated to Israel in 1951. He is petitioning then president of Israel Yitzchak ben Zvi to help his community.

Rabbi Moshe Gabbai, head of the Jews of Zacho Iraq who immigrated to Israel in 1951. He is petitioning then president of Israel Yitzchak ben Zvi to help his community.

The fledgling nation of Israel came to the rescue of Iraqi Jews, including the approximately 25,000 then living in Kurdish areas. Between 1949 and 1952, a series of airlifts, called “Operation Ezra and Nehemia” in honor of ancient leaders who helped restore Jewish life in Israel, brought over 120,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel. Many Jews from Kurdish lands settled in Jerusalem, often helped to flee the country by friendly Kurdish neighbors. Virtually all other Jews from Kurdish areas followed their brethren to the Jewish state; it’s estimated that only a handful of Jews remain living in Kurdish lands today.

Refugee Kurdish Jews in Tehran, Iran, in 1950. Via the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, UC Berkeley.

Refugee Kurdish Jews in Tehran, Iran, in 1950. Via the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, UC Berkeley.

Writer Ariel Sabar’s father was born in Iraq’s Kurdish north. He wrote about him and his family in My Father’s Paradise: A Son’s Search for His Jewish Past in Kurdish Iraq. “The moment his foot touched the ground at Israel’s Lod Airport near Tel Aviv” in 1951, Sabar wrote, “my great-great grandfather Ephraim began to cry. He dropped to his knees, bent forward, and kissed the tarmac.”

As Kurdish Jews stepped off the plane, they were amazed to find themselves in the land of Israel at long last. Sabar writes:

“The Kurds stepping off the Near East Transport planes in their hand-spun jimidani head coverings looked as dazed and disoriented as if a time-travel machine had just deposited them in a distant future. Parents descended the steps to the brightly lit tarmac with wary gazes and armfuls of children. Tired bodies clanked, with teapots slung to belt loops and demon-banishing amulets bunched at necks and wrists. Few had ever before seen an airplane, let alone traveled one.”

For generations, Jews in Kurdish lands celebrated their own unique holiday, called Saharane, during Passover. It mirrored the non-Jewish Kurdish holiday Newroz, and featured singing competitions and outdoor picnics.

Celebrating at a Saharane festival

Celebrating at a Saharane festival

When Jews from Kurdish lands moved to Israel, some worried that Saharane was getting confused with another Passover-time festival, Mimouna. (Mimouna originated with Moroccan Jews and became popular in Israel. It’s celebrated the day after Passover concludes and is marked by visiting friends and neighbors for friendly meals and open houses.) In the 1970s, Kurdish Jews began celebrating Saharane during the Autumn Jewish festival of Sukkot instead.

Today, one of the largest Saharane festivals is held each year in Jerusalem, drawing over 10,000 participants for Kurdish Jewish food, music, and story-telling. In recent years, non-Jewish Kurds have even travelled to Jerusalem’s vibrant Saharane festival from Iraq, Europe, and elsewhere. In 2013, one Syrian Kurd now living in the Netherlands visited Jerusalem’s Saharane festival and explained to an Israeli journalist that even though she’s not Jewish, hearing the Kurdish music and watching people wearing traditional Kurdish dress made her feel at home: “We feel we are a part of Israel.” she explained about her fellow Kurds at the festival, who all received a warm welcome when visiting the Jewish state.

Many Kurdish Jews entered the stonework and construction industries in Israel in the 1950s. Some Israeli towns such as Mevasseret Tzion and neighborhoods in Jerusalem housed vibrant Kurdish communities. Today, over 150,000 Israelis trace their heritage to Kurdish lands. The beautiful songs, foods, traditions and prayers of Jews from Kurdish lands continue to flourish in Israel today.

Photo at top: Refugee Jews from Iranian Kurdistan, 1950 © The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life