Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

7 min read

Esther Cohen, a survivor of Auschwitz, died at the age of 96. This is her story.

It was early in the morning of March 25, 1944. Seventeen-year-old Esther (also known as “Stella” in Greek) Cohen was at home with her parents and six siblings when the call went through the town of Ioannina, near the northwestern border of Greece: all the Jews were being arrested by the Nazi authorities, with the help from local Greek police officers.

For years, the Jews in Ioannina had been keenly following the war, but for much of that time they were relatively safe. Fascist Italy, not Germany, controlled the region, and the Italian authorities did not round up the region’s Jews. However, after Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943, German troops moved into Greece to take over the country. These German Nazis were very different from their Italian former allies. Suddenly, Greek Jews found themselves in the same grave danger as their co-religionists in the rest of occupied Europe, hunted and killed simply for the “crime” of being Jews.

Ioannina’s Jewish leaders did little, hoping that the new German overlords would somehow spare them.

In the early days of the German occupation, Ioannina’s Jewish leaders did little, hoping that the new German overlords would somehow spare them. At first that seemed like it might be the case; the Germans assured Ioannina’s Jewish community that they would be safe. The Jews of the thriving Greek city of Thessaloniki had been arrested and deported to concentration camps, the Nazis explained, but that would not happen to Ioannina’s Jews who were much more integrated and less overtly Jewish, the Nazis assured them.

Indeed, Jews had lived in Ioannina since the destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem in the year 70 CE. The community was Romaniote, an ancient Jewish sub-group with their own distinctive customs and language. The Nazis explained that Thessaloniki’s Jews, which traced their history to the years after the Spanish Inquisition in 1492 when many Sephardi (“Spanish”) Jews fled to Greece, spoke the Jewish language Ladino. That rendered them offensive and different, the Nazis explained, whereas Ioannina’s Jews spoke the Jewish language Romaniot (also called Yevanik) and that made them more acceptable. Though this was palpably nonsense, it seems that the town’s Jewish leaders were willing to be reassured.

In March of 1944, the leader of the Ioannina Jewish Community Board, Dr. Moses Koffinas, was arrested by the Nazis. While in custody, he overheard plans to deport Ioannina’s Jews, and he managed to write a letter to another board member, Sabetai Kabelis, warning him of the plans. For reasons that are lost to history, Mr. Kabelis did nothing to act on Dr. Koffinas’ warning – and on March 25, the entire 1,800 Jewish population of Ioannina was rounded up and sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. A few Jews did manage to escape to the mountains where they joined partisan fighting units, but nearly all the rest of the town’s Jews were slaughtered.

“All you could hear was ‘Oh my God,’ mourning, crying…” Esther Cohen later recalled that horrific morning. “Old people with white hair running wearing their slippers, babies crying, screaming – and my Mom saying how are we going to leave our house? ‘We’ll be back Mom, don’t worry!’”

The Jews were forced at gunpoint to gather in the town’s Mavili square. “When we reached Mavili with their guns pointed at us, the Germans made us get into trucks to begin the journey,” Esther remembered. Years later, she was hardly able to describe what happened next: “I cannot describe – I can’t – why my God, why? What did we do wrong? There is one God for everyone – why do you hurt us so much?”

The Ioannina Jews finally arrived in Auschwitz, where most were sent to their deaths immediately. “The parents, they put them together inside other cars,” Esther remembered, “men, children – cars full of them left. We didn’t see any of them ever again.”

That was the last time Esther ever saw her parents, as the truck they were forced on pulled away to take them to their deaths. Esther and about fifty other girls were left behind to work as slaves. “Girls, defend your honor!” the adults on the truck called out to their precious daughters as they were taken away.

“One day when our heads were being shaved by one of the prisoners,” Esther explains, “she asked me what had become of my parents. I said that I didn’t know. She pointed to the flames coming out of the crematorium and said, ‘There they are, burning.’”

Esther managed to escape from Auschwitz with the help of a Nazi doctor who’d managed to hide from his colleagues the fact that he had some Jewish ancestry. She was ill and in the prison hospital when orders came through to take all of the infirmary’s patients to the gas chambers. The doctor helped Esther hide, and she survived until January 27, 1945, when Auschwitz was liberated by Soviet forces.

Esther found out that out of her entire family only her sister had survived. They were two of the fifty Jews from all of Ioannina who were still alive.

Esther returned to Ioannina and went to her family’s house. “I knocked on the door and a stranger opened it,” she recalled. “He asked me what I wanted and I told him that it was my house. ‘Do you remember whether there was an oven here?’ he asked me. ‘Why yes, of course,’” Esther replied, “‘we used to bake bread and beautiful pies’... ‘Well get out of here then! You may have got away from the ovens in Germany, but I’ll cook you right here in your own home.’ I was horrified.”

Esther remained in Ioannina and married a fellow Jew named Samuel, who was one of the handful of Jews who’d managed to escape to the mountains and had fought the Nazis. Together, they tried to track down some of Esther’s family’s belongings which had been pillaged by her neighbors.

“I found out that the metropolitan bishop had our two singer sewing machines,” she recalled. “I went and asked for them to be returned to me, but I was told that they had been given to the regional authorities. There, they asked me to produce the serial numbers of the machines before they would look for them… I raised my arm and showed them the indelible number from Auschwitz,” she recalled. “‘This is the only number I remember,’ I told them and left.”

Esther and Samuel had a daughter who couldn’t stand the intense anti-Semitism that continued to mark Ioannina. One day in the 1960s, a high school teacher called her daughter a “damn Jew”. “She never got over the insult,” Esther explained. “As soon as she finished the year she moved to Israel. She never came back.”

Despite these and other horrible experiences of prejudice, Esther never left Greece. “We were scared. We were unloved by everyone,” she said, yet still she stayed in the country.

“The world must know that human must not be inhuman.”

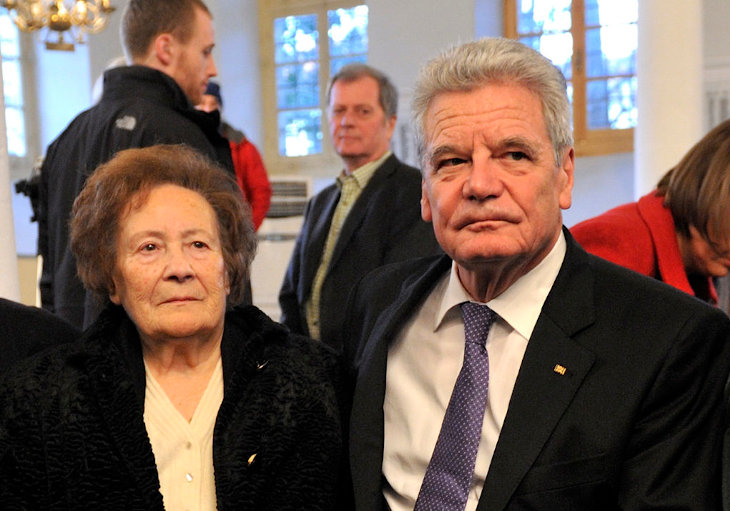

In 2014, German President Joachim Gauck paid an official visit to Greece and requested a meeting with Esther. By then, she was only one of a handful of Jews who were still alive in Ioannina, and at the age of 90, was well known in the country. Esther did agree to meet him, but was unsure what to say. “I feel odd, shaken,” she told journalists before their meeting. “I want to ask him where such hate came from, to burn millions of people alive because it just so happened that they were of a different religion. Should I accept an apology? Nothing can make up for what they did to us. I have no one to see me off when I do die… They left no one; everyone was burned.”

When President Gauck finally did arrive in Ioannina, he visited the town’s synagogue with Esther. Drawing upon the depths of her experience, in that moment Esther did have a key, crucial message to convey to the German President and to the world: “The world must know that human must not be inhuman,” she explained. It was a broken sentence, but conveyed a deep message: we all must hold on to our common humanity, and the horrors of the Holocaust can never be allowed to happen – God forbid – again.