Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

11 min read

A new documentary tells the story of a grotesque romance that saved lives.

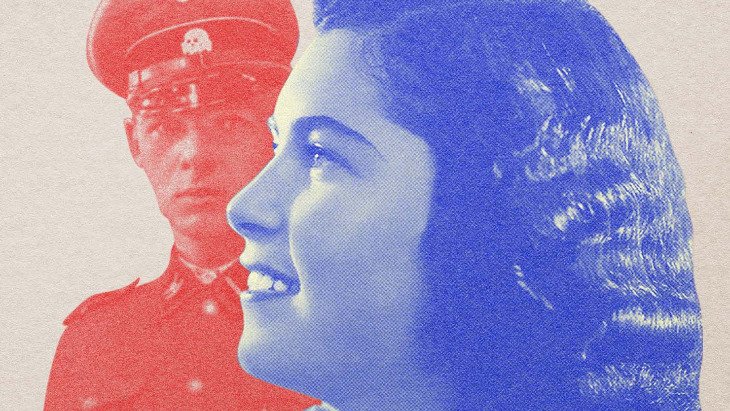

The new documentary Love it Was Not seems like an unrealistic, perverse romance: in Auschwitz, a Jewish prisoner and the SS guard charged with murdering her family and friends fall in love. Or – as the title makes clear – not a normal love, but something resembling romance and affection.

This is no fiction. In the hellhole of Auschwitz, where 1,100,000 million people were murdered – 960,000 of them Jews – a Jewish prisoner named Helena Citronova and a Nazi SS Lance Corporal named Franz Wunsch developed feelings for one another. Their relationship saved the life of Helena’s sister Rozinka.

In 1942, Helena was one of 997 Jewish teens and young women sent to Auschwitz during the first official transport of Jewish prisoners to the death camp. They’d been told by Slovak authorities that they were going to do national work service for a few months. In reality each of the prisoners was sold by the Slovak government to the Nazi authorities for 200 Reichsmarks (about $500) per prisoner.

When the girls arrived at Auschwitz they immediately realized they’d been tricked. “We were teenagers,” recalled one survivor, Edith Grosman, who was amongst that first transport. “We were still young enough to want to throw temper tantrums, to be lazy, to shirk a duty or to sleep late. Only a month ago we were giggling and gossiping about the latest bit of news in our community, and now we were seeing girls dying...already dead before their time. And then there is the question, will that be me too? Will I be dead soon, too?” (Quoted in The Nine Hundred: The Extraordinary Young Woman of the First Official Transport to Auschwitz by heather Dune Macadam. Hodder & Stoughton: 2020.)

One of the terrified Jewish women in that group was Helena Citronova, a 20-year-old daughter of a cantor in Slovakia. After she arrived in Auschwitz, Helena was used as slave labor. Her first job was helping demolish a ruined building at the camp. Guards forced the girls to stay at the job site even when parts of the building they were demolishing fell down. “We weren’t allowed to run, so when the wall came down, the first girls were crushed and died on the spot,” she later described.

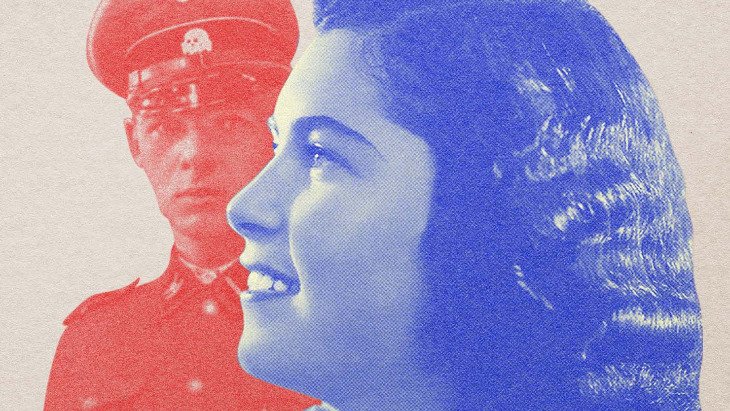

Helena Citronova

Helena Citronova

Later on, Helena got a job that was prized by the prisoners: the easier work of sorting the belongings of murdered Jews in an enormous warehouse which the prisoners nicknamed “Canada”. On her first day working in the warehouse, Helena was ordered to perform yet another task: the day – March 21, 1942 – was the birthday of Franz Wunsch, one of the SS guards in charge of the gas chambers at Auschwitz. Helena was asked to sing for him at his birthday party. If she made a good impression, Helena was told, she might get to stay in the warehouse work detail. Helena decided to do all she could to make a good impression.

At age 20, Wunsch was already a hardened Nazi. He’d volunteered for the ruthless SS when he was a teenager. At Auschwitz, he was responsible for unimaginable brutality. Years after the war, he stood trial in his native Austria, charged with shooting and murdering Jewish prisoners, especially members of the Sonderkommando, the Jewish concentration camp laborers who were compelled to force Jews into the gas chambers, remove their bodies once they’d been killed, burn the bodies in Auschwitz’s huge crematorium, and dump the ashes into a river. Wunsch was also accused of personally inserting the canisters of poison gas into the chambers in which Jews were killed.

He asked her to please sing the song again. His request startled the terrified Jewish prisoner.

At his birthday party that day in Auschwitz, Wunsch watched as Helena sang birthday songs, tears streaming down her cheeks. She later recalled that she was sure she was soon going to die, and sang with passion as she believed it might be the last time she ever got to sing. She only knew a few German songs, including the melancholy song Love it Was Not, which lends the new documentary about Helena and Wunsch its title.

Watching her sing, Wunsch longed to connect with Helena. He asked her to please sing the song again. His request startled the terrified Jewish prisoner. “Suddenly I hear the voice of a human being,” Helena later recalled, “not the roar of animals. I heard the word ‘please’. I look up with tears in my eyes and see a uniform and I think, ‘God where are the eyes of a murderer? These are the eyes of a human being.’”

Helena returned to work in the “Canada” warehouse, sorting the possessions of murdered Jews, and Wunsch visited her later on, tossing her a letter he’d written. “When he came into the barracks where I was working, he threw me that note. I destroyed it right there and then, but I did see the word ‘love’ – ‘I fell in love with you,’” Helena recalled years later from her home in Israel. “I thought I’d rather be dead than be involved with an SS man. For a long time afterwards there was just hatred. I couldn’t even look at him,” she described.

I thought I’d rather be dead than be involved with an SS man. For a long time afterwards there was just hatred. I couldn’t even look at him.

Wunsch continued to pursue Helena, hopelessly besotted by her. His affection didn’t extend to helping her escape, but he did smuggle her extra food and clothing beyond the starvation rations and thin prison uniforms that contributed to Auschwitz prisoners’ torment and deaths. Helena later described that helping her in this way put Wunsch’s life at risk with his superiors in the SS. He gave her extra sheets and blankets, and turned over his own food rations to her, even giving Helena the gifts of food that his mother sent him.

“He loved me to the point of madness,” Helena later described. She shared the food Wunsch gave her with other inmates, helping save their lives. At times, Helena asked Wunsch to help save the lives of her fellow inmates. There were times when she personally grabbed his hand while he was beating a Jew to ask him to stop.

Sisters Helena and Roza with Roza’s daughter, Aviva, who later perished at Auschwitz at the age of just nine.

Sisters Helena and Roza with Roza’s daughter, Aviva, who later perished at Auschwitz at the age of just nine.

Some of her fellow prisoners were grateful, but many others were intensely jealous of the gifts and safety being lavished on Helena while they faced death every day. “Everyone was jealous, deeply, of the very fact that she had that chance, and we would go like sheep to the slaughter,” one of Helena’s fellow Auschwitz inmates describes in the documentary.

A turning point came when Wunsch was able to help Helena’s sister. Her sister Rozinka and her two young children – a nine-year-old girl and newborn baby boy – arrived in Auschwitz and had been selected for death to be sent to the gas chambers immediately. Hearing the news, Helena ran to the gas chamber and first pleaded with the SS guards to spare their lives; when they refused, Helena begged them to kill her too.

The guards were about to comply, when Wunsch ran up and began to violently beat Helena for the crime of violating curfew. While he beat her, he secretly whispered to her, to tell him her sister’s name.

“So he said to me, ‘Tell me quickly what your sister’s name is before I’m too late,’” Helena later described. “So I said, ‘You won’t be able to. She came with two little children.’ He replied, ‘Children, that’s different. Children can’t live here.’ So he ran to the crematorium and found my sister.’” Helena’s sister survived, though the children were murdered.

It’s impossible for us to look back at this period and fully understand what a prisoner like Helena Citronova was going through. With her family and friends and fellow Jews being murdered around her night and day, for years, after watching her precious little niece and nephew killed in front of her, any kindness or help must have seemed overwhelming.

In this picture taken at Auschwitz, Helena looks happy, healthy and “almost plump” – in sharp contrast to its other inmates.

In this picture taken at Auschwitz, Helena looks happy, healthy and “almost plump” – in sharp contrast to its other inmates.

In time, it seems that Helena began to develop some affection for Wunsch in return. In the documentary, Helena's contemporaries stress that Helena and Wunsch were never physically intimate. That would have been impossible in the strictly controlled environment of Auschwitz. But Wunsch's many gifts and favors to Helena were clearly visible for everyone to see.

Before her death in 2005, Helena told the British filmmaker Laurence Rees, “Here he did something great. There were moments where I forgot that I was a Jew and that he was not a Jew and, honestly, in the end I loved him.”

Wunsch took a photograph of Helena in her striped prisoner's uniform and kept it with him all the time. It’s a jarring image: standing in the hell of Auschwitz, wearing its degrading uniform, Helena smiles radiantly; she looks almost happy and healthy. According to his daughter Dagmar, Wunsch was obsessed with that photo. He made many copies of it so that he could cut out Helena’s face and juxtapose it on other photographs, making it look like Helena was safely someplace other than Auschwitz.

That became a motif in the movie Love it Was Not. Israeli director Maya Sarfaty uses that portrait of Helena throughout her film, placing Helena in different settings: in the barracks at Auschwitz, in the crematorium, and at Wunsch’s eventual trial years later.

After the war ended, Helena and her sister Rozinka tried to return home to Slovakia. (His last act of aid to Helena was giving her and Rozinka warm, fur lined boots for the journey.) They found the Jewish community in their former home utterly destroyed,

Wunsch searched for Helena for years after the war and wrote to her time and again. “Then we will be together and keep the many promises we made each other,” he wrote. “How completely different it would have been if we had won the war.”

Within a year of being liberated from Auschwitz, she married a Zionist activist and they moved to Israel together.

Helena avoided these letters. Within a year of being liberated from Auschwitz, she married a Zionist activist and they moved to Israel together. One of Helena’s relatives wrote to Wunsch demanding that he stop writing to Helena. There was no way Helena could be in touch with “Nazi criminals,” she wrote, adding that the blood of Helena’s little niece and nephew he allowed to be murdered “will never be washed off your hands.”

Wunsch returned to Austria, married, and started a family of his own. In 1972, he was put on trial for war crimes. Witnesses who’d seen his brutality described Wunch’s sadism. He viciously beat prisoners and personally killed Jews. He selected which Jews would go to the gas chambers to die and which would live to work as slave laborers.

Wunsch seemingly never kept his infatuation with Helena a secret from the family he built after the war, and his wife wrote to Helena, begging her to come and testify on Wunsch's behalf. Helena did so: she travelled to Vienna and described in court how Wunsch had been kind to her – and also how she’d seen him be brutal to other Jews. In the end, Wunsch was acquitted. The judge at the trial stressed that Wunsch wasn’t innocent, but the statute of limitations on war crimes in Austria at the time prevented his conviction.

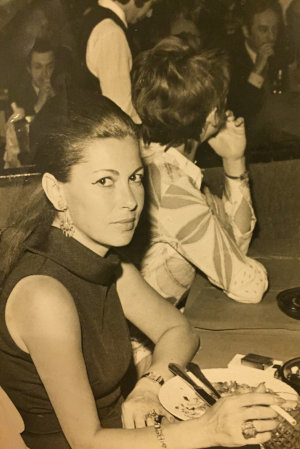

After the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945, Helena began a new life in Tel Aviv, Israel.

After the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945, Helena began a new life in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Helena returned home to Israel, the fleeting friendship and romance she’d once shared with Wunsch long dead. She never got over the trauma of her experiences during the Holocaust. In the documentary, her three children describe the difficulties Helena always had as a result. She was often very angry and sometimes profoundly unhappy.

After his trial, Wunsch insisted that his infatuation with Helena altered him for the better. “Desire changed my brutal behavior,” he said. “I fell in love with Helena Citronova and that changed me. I changed into another person because of her influence.’

Years ago, in the hell that was Auschwitz, Helena Citronova used every means she could to live and to help her beloved sister and fellow inmates. It wasn’t easy, and it’s impossible for us to grasp what she went through and judge the personal choices she made. Helena was determined to survive, and the family she built in Israel today is testament to her strength and resilience.