Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

11 min read

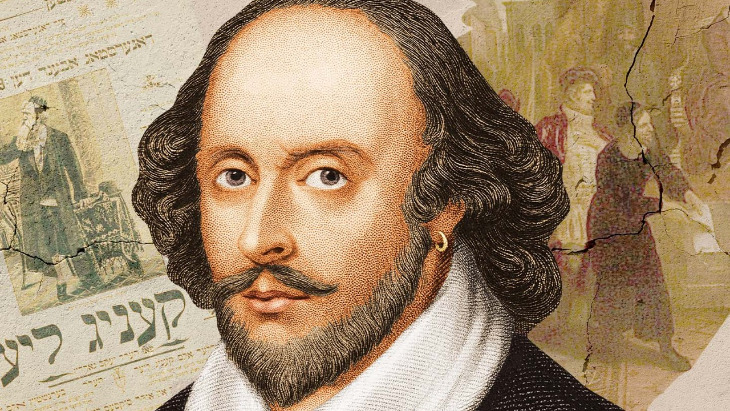

How the Bard’s plays defined the way audiences look at Jews for generations.

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? …warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

These lines from William Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice are among his most famous. In the play, Shakespeare indulged in horrible anti-Jewish stereotypes, yet also depicted Jews as real people with feelings and emotions, a thought that was revolutionary at the time.

Shakespeare influenced the ways that Jews have been perceived for hundreds of years. Here are seven little-known facts about Shakespeare, his plays, and Jews.

When Shakespeare was born in 1564, Jews had been banned from living in England for 274 years. In the year 1290, England’s King Edward I officially barred any Jewish settlement in his kingdom and expelled England’s sizable Medieval communities.

Yet Jewish communities did flourish in several towns in England, in secret. Prof. James Shapiro of Columbia University combed historical records for any mention of Jews living in England during Shakespeare’s day, and found myriad references to secret Jewish communities. In 1540, a family was brought to court in London on charges of maintaining their “Jewish and heretical faith” in secret. That same year, official documents record other people “suspected to be Jews” being arrested, also in London.

Given that there were secret Jewish communities living in London at the time, it’s possible that Shakespeare knew London Jews.

Several references exist to secret Jewish communities in Bristol, about 120 miles from London, during the Renaissance. Portuguese Jews lived in the city, possibly having escaped from the Inquisition in their native land. At least one Ashkenazi Jew, a Prague-born Jewish man named Joachim Gaunse, lived openly for a time in Bristol in the 1580s. (He was eventually arrested on the charge of not believing in Jesus; it’s unclear what the outcome of his case was.)

In his book The Woman Who Defied Kings: The Life and Times of Dona Gracia Nasi, Andree Aelion Brooks describes a clandestine route established by the secret Portuguese Jew Dona Gracia Nasi in the 1500s. She ran a trading empire and would hide Jews in her ships to smuggle them out of Inquisition-dominated Spain and Portugal (where being a secret Jew could result in torture and death) and bring them into England. There, a Jewish agent known as Christopher Fernandes would ferry the fleeing Jews onto boats bound for the Netherlands, where Jews could live openly.

Portrait of Gracia Mendes Nasi.

Portrait of Gracia Mendes Nasi.

It’s impossible to know whether or not Shakespeare ever met a Jew. Virginia Woolf famously imagines what Shakespeare’s life was like, in her well-known essay “A Room of One’s Own”. After an extensive classical education, Shakespeare went “to seek his fortune in London. He had, it seemed, a taste for the theater; he began by holding horses at the stage door. Very soon he got work in the theater, became a successful actor, and lived at the hub of the universe, meeting everybody, knowing everybody, practiced his art on the boards, exercising his wits in the streets, and even getting access to the palace of the queen.” Given that there were secret Jewish communities living in London at the time, it’s possible that Shakespeare knew London Jews.

While Shakespeare was living and working in London (he moved to the capital in about the year 1585), he lived within a few miles of another Londoner, a secret Jew named Roderigo Lopez. In 1594, Lopez was arrested and charged with treason and plotting to kill Queen Elizabeth I. His trial gripped all of London: Shakespeare might have been among the throngs watching Lopez’s court case and subsequent execution. The “Lopez Affair” became a defining event of the era.

Lopes (right) speaking with a Spaniard (engraving by Esaias van Hulsen)

Lopes (right) speaking with a Spaniard (engraving by Esaias van Hulsen)

Lopez was a secret Jew, born in 1524 in Portugal. When it seemed that his Jewish faith might be unmasked, Lopez fled to England where he changed his first name to Ruy and began to practice the medicine that he’d studied back in Portugal. He was a popular physician and quickly attained a high degree of stature and respect in London, specializing in prescribing herbs such as anise and sumac, which today are recognized as having beneficial effects.

Queen Elizabeth I named Lopez her royal physician in 1584. It’s unclear how secret his Jewish faith remained, but it seems he was known at least to some people as a crypto-Jew. Lopez found himself with some powerful enemies, including the Earl of Essex, who was a close confidante of the queen.

Queen Elizabeth I

Queen Elizabeth I

Seeking to rid the court of his arch-enemy, the Earl of Essex accused Lopez of plotting to poison the queen. Queen Elizabeth delayed his trial three months, refusing to believe that her trusted physician would seek to harm her. Eventually, his enemies accused Lopez of treason, leaving the queen with no choice but to try him. The official record of his trial notes that Lopez “like a Jew, did utterly with great oaths and execrations deny all.” His Jewishness was front and center during his trial, and sparked anti-Jewish hysteria across the capital.

Lopez was found guilty and was publicly executed in 1596. An enormous crowd watched his death and filled the air with chants of “Hang the Jew!” Shakespeare based his character Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, which was first performed in 1605, on Lopez and his trial.

The Merchant of Venice wasn’t the only play during Shakespeare’s life to depict Jews. In 1596, London readers were treated to a work of fiction called The Orator written under the pseudonym Lazarus Piot (likely the author Anthony Munday). One plot line bears a marked similarity to The Merchant of Venice and depicts a Jew who demands a “pound of flesh” from a Christian borrower in payment of a debt. (In The Merchant of Venice, an evil Jewish moneylender named Shylock demands payment from the Christian character Antonio, even if it kills him.)

In 1571, Queen Elizabeth I had made the dramatic change of legalizing money-lending in England, spawning endless debates about the newly widespread phenomenon of interest-charging loans. Commercial lending was a contentious issue, discussed endlessly in private conversations across in England in the late 1500s, as reflected by usury being a central theme in some English plays.

The Trial Scene, 'The Merchant of Venice', Act IV, Scene 1. Oil on canvas by Robert Smirke.

The Trial Scene, 'The Merchant of Venice', Act IV, Scene 1. Oil on canvas by Robert Smirke.

In 1583, London theatergoers watched The Three Ladies of London by playwright Robert Wilson. This play also featured a Christian borrower who was indebted to a Jew, though in this play it’s the Jewish lender who’s depicted as the more honorable character.

A few years before Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice premiered, audiences watched The Jew of Malta by Christopher Marlowe, first performed in 1592. It features a dastardly, evil Jew named Barrabas who hates all that is good and pure and fiendishly plots to kill his many enemies, including an entire convent full of nuns and a priest. The play ends with Barrabas being burned at the stake. Shakespeare scholar Bernard Greenbanier, who taught at Brooklyn College from 1926 to 1964, has written that The Jew of Malta can be read primarily as a critique of Christian morals at the time. It did so, however, by creating a horrible caricature of a Jew which shaped audiences’ expectations of what Jewish characters looked like.

In The Merchant of Venice, the Jewish character Shylock is odious, but he also is depicted as human. There can be some sympathy as we watch him. Yet in many of his other plays, Shakespeare displayed the same casual antisemitism that marked his contemporaries.

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

Thus, in the famous cauldron scene in Macbeth, one of the disgusting ingredients the witches toss into their potion is “liver of blaspheming Jew”. In Two Gentlemen of Verona, the character Launce complains that another character “has no more pity in him than a dog. A Jew would have wept” yet he did not. In Much Ado About Nothing, the character Benedick declares his love for Beatrice, saying “if I do not love her, I am a Jew.” For Shakespeare, as for most Englishmen at the time, Jews were shorthand for something bad, not real human beings.

British Lawyer Anthony Julius has observed that ever since it was written, The Merchant of Venice has been used to depict whatever anti-Jewish stereotypes were most prevalent at the time. “The reception history of the play confirms that Shylock is taken by reader and audience to be a representative Jew.”

The 1943 production of The Merchant of Venice directed by Nazi-party member Lothar Müthel

The 1943 production of The Merchant of Venice directed by Nazi-party member Lothar Müthel

The play’s negative depiction of Jews made it a favorite in Nazi Germany. Between 1933 and 1939, there were over 50 performances in Germany. Audiences were encouraged to boo and jeer whenever Shylock appeared on the stage. A special performance of the play marked the day in 1943 when Vienna officially announced that it was Judeinrein, empty of all Jews.

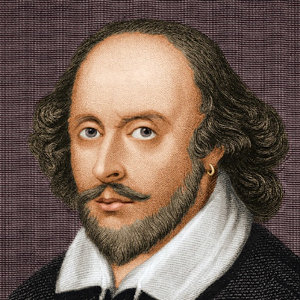

Shakespeare’s theater troupe was known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. In 1599 they built their own theater building in London called the Globe Theater. After that theater burned down, a second Globe Theater was rebuilt in 1614. The theater closed 28 years later, and in 1997 it was rebuilt once again near its original location near the River Thames; it’s since become a popular tourist destination in London.

The Globe Theater

The Globe Theater

Audiences are encouraged to be loud and rowdy, just as they were in Shakespeare’s day. That behavior wasn’t the only way in which audiences mimicked Shakespeare’s times. During one early performance of The Merchant of Venice in 1998, audiences hissed and booed at Shylock, jeering whenever the Jewish character appeared onstage. Theater critic Carole Woddis wrote that watching the play in the newly rebuilt Globe “still uncomfortably reinforces racial, Jewish stereotypes.” (Responding to criticism, then Globe director Mark Rylance robustly defended the audiences’ reactions as part of an authentic theatrical experience.)

During the heyday of Yiddish theater, Shakespeare’s plays were perennial favorites, translated into Yiddish and sometimes altered to include more Jewish storylines. “By the early 1890s American Yiddish actors were wild about Shakespeare,” notes Joel Berkowitz in his book Shakespeare on the American Yiddish Stage (University of Iowa Press: 2010). Yiddish-speaking audiences in New York could watch Yiddish versions of Hamlet, Othello, Romeo and Juliet, and even The Merchant of Venice.

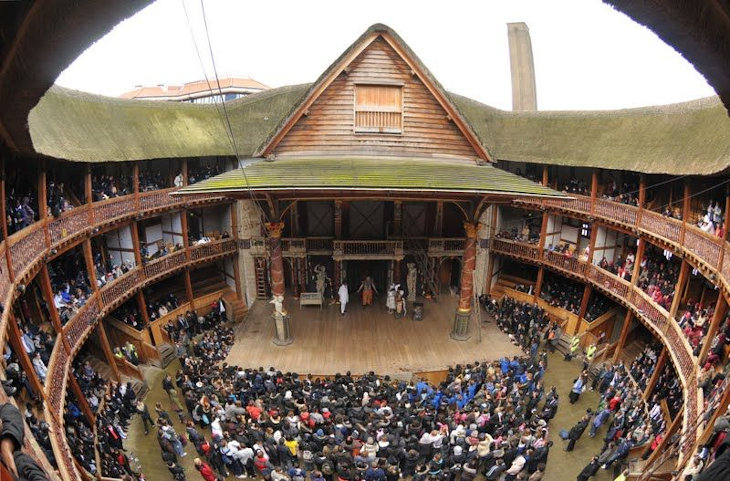

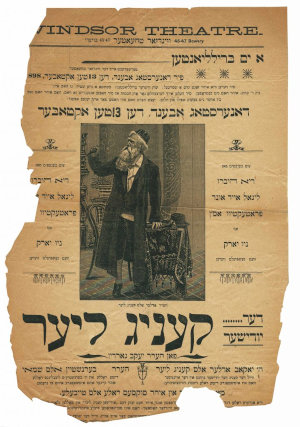

King Lear in Yiddish

King Lear in Yiddish

Sometimes Shakespeare’s plays in Yiddish were advertised as ibergezetst un farbesert – translated and improved. That was certainly the case with The Jewish King Lear, premiered in 1892. In this version, the hero is Dovid Moysheles, a Jewish merchant from Vilna who decides to divide his estate between his three daughters and move to the Land of Israel. (Like King Lear, Moysheles misjudges his daughters’ characters. He ends up as a homeless, blind beggar, accompanied by his trusted servant Shammai.) The play was made into a feature film in 1934, and lives on a testament to the enduring popularity of Shakespeare’s plays. Endlessly elastic and interesting, able to be recycled and reinvented, Shakespeare’s works continue to challenge and entertain.

For further reading: