Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

13 min read

Josef Levkovich’s dramatic encounters with the villain of Schindler’s List. An Aish.com exclusive.

Josef Levkovich was a teenage slave laborer when Amon Goth, the villainous “Butcher of Plaszow” who murdered Jews for sadistic sport, pointed his gun at Josef’s head.

“I was working at the Plaszow concentration camp, dismantling the remnants of a Jewish cemetery,” Josef told Aish.com from his home in the Arzei Habira neighborhood of Jerusalem. The cemetery’s wrought iron fence – all 150 tons – was needed to make weapons for the Nazi slaughter of millions across Europe.

Josef was high atop the fence, removing some bricks, when Goth rode up on his horse – flanked by two snarling dogs trained to tear inmates to death. “When I saw Goth coming, I quivered with fear,” Josef says. “I’d been attacked by these dogs before.” In that attack, Josef protected his face with his hands; he bore the scars for a lifetime.

“Up on the fence, my job was to carefully remove each brick, then toss it down to another prisoner,” Josef explains. “But when Goth passed by, the other prisoner dropped the brick.”

Goth shot him on the spot.

“Goth shouted to me: ‘Throw down a brick!’” Josef vividly recalls. “I did, but Goth let it fall to the ground.”

“Goth pointed his gun at my eyes. I said Shema Yisrael and blacked out.”

Goth ordered Josef off the fence. He quickly slid down, cutting himself badly in the process.

“Goth yelled at me, took out his gun, and pointed it at my eyes,” Josef says. “I knew my life was over. I said Shema Yisrael and blacked out.”

Josef awoke a few days later in the infirmary, in pain and with bandages covering his entire body. Details of what transpired became known only later when Josef later met Wilek Chilowicz, head of the Jewish police who was always at Goth's side and was there at the time. “Chilowicz knew me because I’d volunteered to shine his shoes,” Josef says. “He told me: ‘I saved your life! Goth wanted to shoot you, so I beat you up and told Goth: ‘Save your bullet – he’s dead.’”

Fast forward seven years, post-war. Twenty-year-old Josef is a community activist. He’s successfully rescued 600 Jewish orphans (details later), and was now ready for the challenge of hunting Nazi war criminals.

Josef interviewed people and combed records, gathering every thread of information where Nazis might be hiding. One day, he was searching for clues at a POW camp near Vienna that held 30,000 German prisoners. “I asked a German officer if he recognizes all the soldiers in his group, and he told me: ‘There is one stranger we don’t know.’

“I approached what appeared to be a regular Wehrmacht soldier, and my blood began to boil. It was Amon Goth hiding his identity!”

Josef snuck up behind Goth and years of pent-up frustration let loose. “I started screaming, spitting and beating him – rattling off the list of atrocities I’d seen him commit in the camp.”

Josef snuck up behind Goth and began screaming, spitting and beating him.

Goth was arrested, put on trial in German court, and condemned to hanging. “He was happy to have it all over,” Josef says. But the Polish government insisted he be extradited and put on trial in Poland where he’d committed his crimes. Josef says: “I was happy because this meant I could repeat my accusations against him, and his suffering would be prolonged. He deserved it.”

In Poland, Goth was sentenced to death and was hanged in the Plaszow camp, on the same spot where he’d sadistically murdered untold innocent Jews.

The Holocaust film Schindler’s List would immortalize Goth as the paradigm villain.

During this time, Josef met Oskar Schindler in a DP camp. “He heard that I was looking for Nazi war criminals, and wanted me to know that he was one of the ‘good ones’,” Josef says.

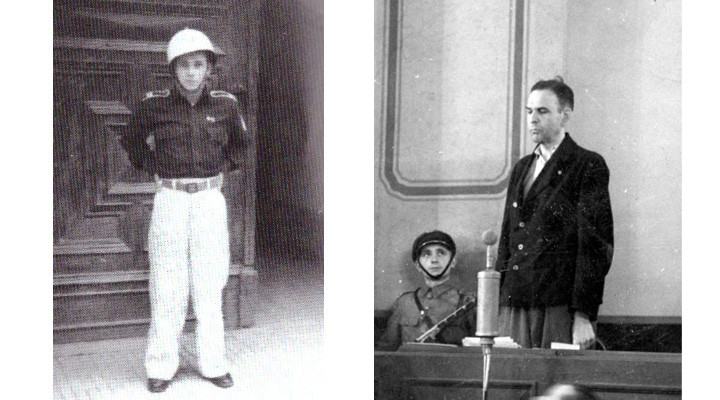

Left: Josef on the day he caught Amon Goth. Right: Goth on trial for war crimes.

Left: Josef on the day he caught Amon Goth. Right: Goth on trial for war crimes.

Josef Levkovich was born in 1926 in the Polish village of Dzialoszyce (pronounced zoli-shitz), the oldest of four brothers in a well-known Polish family. A street named Levkovich (Lewkowa) encircles Krakow’s town square, and their ancestral home today serves as the local police station.

“Before the war, we figured we were safe in Poland,” Josef says. “Jews had lived there for centuries. We were Polish citizens, protected by Polish law. In our wildest dreams we never imagined being deported to factories of death. When the Nazi oppression began, no one defended us. Most Poles followed Nazi orders, some even helped to round up Jews."

We figured we were safe in Poland, but the Polish police followed Nazi orders, even helping to round up Jews.

In 1939, when Jews were forced to relinquish all their possessions, Josef’s uncle sold his textile business to a non-Jew in exchange for a hiding place. That arrangement lasted a short time, Josef recalls. “When the man feared being discovered, he took my uncle and his entire family out to a field and murdered them.”

At age 13, Josef vowed: “If I survive, I will go back to find that man and give payback.” (After the war, Josef could no longer remember the man’s name.)

As the Nazis tightened their grip, Josef and 15,000 other Jews were herded to a flooded field where they were forced to sit all night, cold and hungry, in waist-high water. The elderly were pulled to the side and shot dead.

The next morning, 95% of those Jews – including Josef’s mother and brothers – were taken to the Belzec camp for immediate extermination. A remnant of 800 Jews were sent to slave labor, Josef and his father among them.

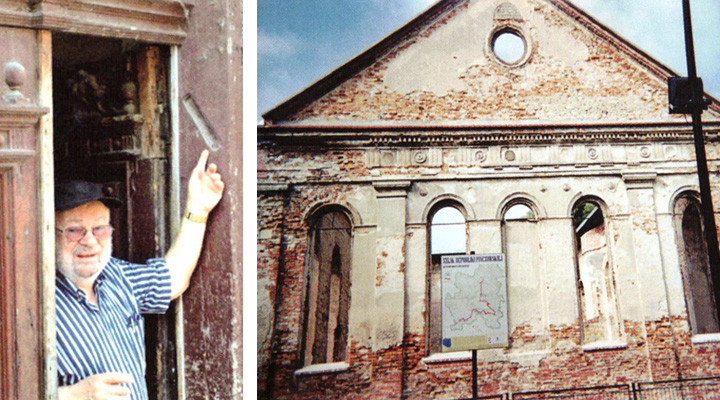

In 2011, Josef visits his childhood home and synagogue in the Polish village of Dzialoszyce.

In 2011, Josef visits his childhood home and synagogue in the Polish village of Dzialoszyce.

Throughout the years, Josef was transferred from concentration camp to concentration camp. He recalls one incident at Melk, a sub-camp of Mauthausen:

“Because I’m short, I was always in the front row for morning inspections. One day, the camp Kommandant, Julius Ludolf, stopped right in front of me. Without thinking, I saluted, clopped my wooden shoes together, and said in German: ‘Sir! I will shine your boots to shine like the sun!’”

The next thing he knew, Josef was being led by an officer outside the camp to Ludolf’s magnificent villa atop a hill.

“After a while,” Josef recalls, “Ludolf came. Instead of speaking, he made barking noises like a dog, which I understood meant to shine his boots.”

Josef was then led to a garden and given the daily task of feeding the Kommandant’s rabbits and chickens. This gave Josef access to animal food, far better than he was eating in the camp. “I was happy to see carrots for the rabbits,” he says, “and I was the first ‘rabbit’ to be fed!”

In the evenings, Ludolf would throw parties at the villa for SS officers. “They threw out a lot of food, which I ate,” Josef says. He also smuggled food into the camp, risking his life to feed dozens of other prisoners.

At the villa, a lieutenant named Otto Striegel enjoyed mistreating Josef. “He’d order me to stand in the corner with my mouth open, then try throwing pebbles into my mouth. They usually ended up hitting me in the face.”

[While Nazi hunting after the war, Josef discovered Kommandant Ludolf hiding in a village. Josef testified in court, telling of Ludolf’s crimes and his huge quantity of stolen jewelry, gold and foreign bank notes. Ludolf and the lieutenant who threw pebbles were both executed.]

Even though Josef spent so much unattended time at the villa outside the camp, he didn’t try to escape.

“I’d managed to escape previously,” he says. “I slipped away from a work detail and wandered in search of someone to give me food or shelter. But people slammed the door on my face. Either they were cruel or afraid; it is not for me to judge.”

The next morning, Josef went back to the slave labor camp; there was no better option.

“In the cattle car, we had no air or water. Every few minutes, another person died.”

Another treacherous time, Josef was put onto a cattle car headed for Auschwitz. “We were 160 men in the car, packed so tight, worse than sardines,” he says. “We had no air or water. Every few minutes, another person died. When we arrived in Auschwitz, I was standing on so many layers of bodies that I reached the roof.”

Of the original 160 men, 20 walked out. Josef’s first job in Auschwitz was to carry those dead Jews to the crematoria.

Josef pauses and thinks back to those hellish times:

“I endured bitter cold and never-ending hunger. But no matter how grim the situation, I found the courage and faith to survive. Even during the worst times, God filled my entire inner being. I never felt abandoned. The Nazis could destroy my life, but not my belief. That kept me alive.”

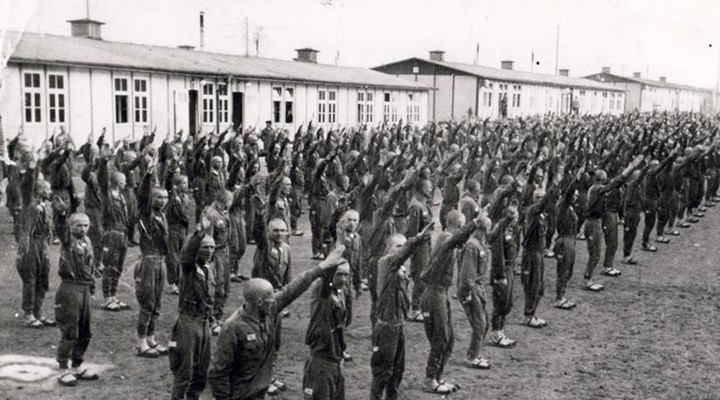

Morning roll-call in Mauthausen.

Morning roll-call in Mauthausen.

One morning in May 1945, the camp was eerily quiet. No siren signaled morning roll call. Then at midday, Josef and the others were suddenly ordered to assemble in the camp’s appelplatz (center square). The SS Kommandant strutted onto a stage and announced: “We want to protect you from the enemy. Go quickly into the tunnels!”

Josef describes:

“Rumors spread that the tunnels were rigged with dynamite, and the Nazis planned to blow us all up. Thousands of prisoners began shouting, ‘Nein! Nein!’ (No! No!). The SS sprayed the crowd with machines guns. I dropped to the ground. Many did not escape the flying bullets and died on the spot.”

Eventually the firing stopped and Josef stood up to see bodies scattered everywhere. The stage was empty. The SS had vanished.

“I was stunned,” he says. “Was the nightmare finally over? Miracle of miracles – had our dreams of freedom finally come true? Was it possible I’d survived five horrific years of slave labor, beatings, and starvation?”

Josef bent down and picked a revolver off the ground. He had no clue how to use it, but today was a new day.

Josef at home in Jerusalem, surrounded by family photos.

Josef at home in Jerusalem, surrounded by family photos.

Liberated at age 17 and weighing 60 pounds, Josef pondered his next move. He was literally alone – the only member of his extended family to survive.

As an orphan, Josef was concerned about the thousands of Jewish children who, at the outset of war, had been “temporarily placed” with non-Jewish families and monasteries. In many cases, entire Jewish families had been killed, with nobody to reclaim these children. Josef knew, “If I don’t do something, these Jewish children will be lost to the Jewish people forever.”

With no idea how to achieve this gargantuan task, Josef discovered a distant cousin named Daniel who was a Communist leader in post-war Poland. “I told him that I have an idea to unite families that the Nazis separated. I put it in secular terms, because ‘Jewish’ was a hated term in Poland.”

Daniel introduced Josef to a Polish general who agreed to help the rescue activities – supplying a team of 40 people, including 20 soldiers, rifles, trucks, a tank(!) – and total authority to fend off anyone who might resist.

Locating these orphaned Jewish children was like looking for a needle in a haystack. Through a network of informants, Josef would follow leads to a particular address.

Josef succeeded in rescuing 600 orphans.

“We’d knock on the door, show our badge, and say, ‘We’d like to ask a few questions. Is this your daughter? Show us her birth certificate.’ Many times they claimed the child was adopted, so we’d insist: ‘Show us the adoption papers!’”

Josef had a keen sense for spotting Jewish children and – working with psychologists and security personnel – succeeded in rescuing 600 orphans.

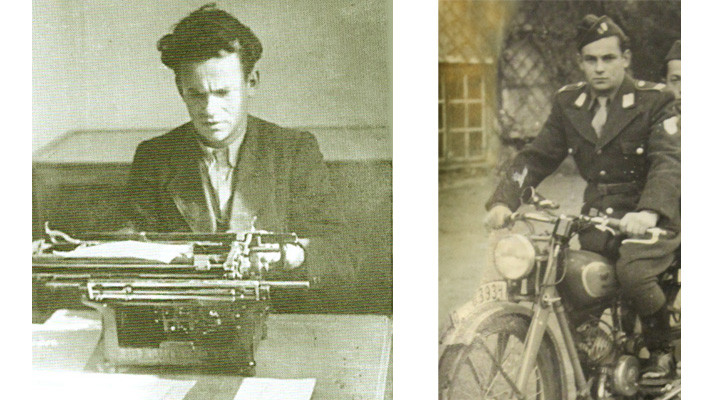

In the aftermath of the war, Josef was a devoted and successful activist.

In the aftermath of the war, Josef was a devoted and successful activist.

Josef became involved with the Zionist movement and was headed toward a career as a diplomat. One day, he saw a Red Cross announcement that someone in Buenos Aires was looking for information about the Levkovich family. It was Josef’s great-uncle. “I was a lone survivor. I was eager for family. So I answered the call and they sent me a ticket to come by boat to Argentina.”

Josef became a diamond dealer and met his wife Perla in Columbia, South America. When their oldest son reached school age, they moved to the larger Jewish community of Montreal, Canada. Josef continued working in the diamond business, even operating a diamond factory in Communist Cuba.

He bemoans one deal that got away. Mrs. Pablo Picasso wanted to swap some of her husband’s paintings for diamonds. The paintings were appraised at a few thousand dollars each, but Josef thought they looked odd and passed on the deal. He says: “Today those paintings are worth about $30 million – each!”

In the 1980s Josef became involved in a development company that built projects all over Israel. They built Arzei Habira, a residential neighborhood in Jerusalem, where Josef secured the apartment he lives in today. One apartment project in Rechovot was given the street name Levkovich.

Levkovich street in the central Israeli city of Rechovot.

Levkovich street in the central Israeli city of Rechovot.

Over the decades, Josef supported the State of Israel, meeting with Prime Ministers and other high government officials, and helping to establish diplomatic and economic relations between Israel and South American countries.

In 2016, Josef decided to leave his comfortable life in Canada and make aliyah. An Israeli TV crew stayed in Montreal for an entire week to document it.

“I wanted to make aliyah for many years, but I said if I don’t go now, at age 88, I never will,” Josef says. “I’m very happy I made the decision. I found so many friends and good neighbors.”

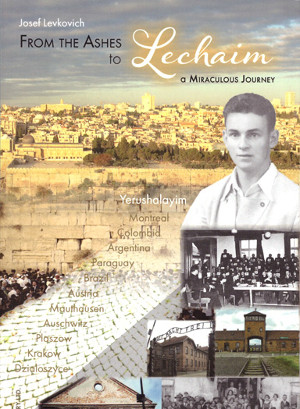

For many years, Josef refused to speak about his Holocaust experiences. His children and grandchildren pushed him to write a book, so his story would be remembered. The result is From the Ashes to Lechaim: A Miraculous Journey, published this year as a small print run for family and friends.

For many years, Josef refused to speak about his Holocaust experiences. His children and grandchildren pushed him to write a book, so his story would be remembered. The result is From the Ashes to Lechaim: A Miraculous Journey, published this year as a small print run for family and friends.

“I realized that if I don’t tell my story, nobody will. I lost my entire connection to the past, and now I must alert generations to come,” he says.

In 2011, Josef traveled back to Poland with his youngest son, visiting Krakow, Auschwitz, Belzec, where his mother and brothers were murdered, and Dzialoszyce, the village where he grew up, and Plaszow, where he survived the dark shadow of Amon Goth.

“No matter how much is written about the Holocaust,” he says, “it is impossible to describe the terror, and starvation. For five years, from morning till night, I did back-breaking labor in quarries, railroads, and salt mines. I eagerly did everything I was asked. I was occupied with just surviving the moment, with no time to think. Otherwise, I’d go crazy.”

Those memories still haunt today. “I often wake up during the night, soaked with sweat,” Josef says. “Last week I dreamed of fighting with a Nazi who wants to shoot me. I grabbed his rifle and turned it around on him.”

Josef Levkovich rescued 600 orphans, captured Amon Goth, and built a beautiful life. After the nightmare, this is revenge.

Josef’s 90th birthday with “his legacy”: four generations.

Josef’s 90th birthday with “his legacy”: four generations.