Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

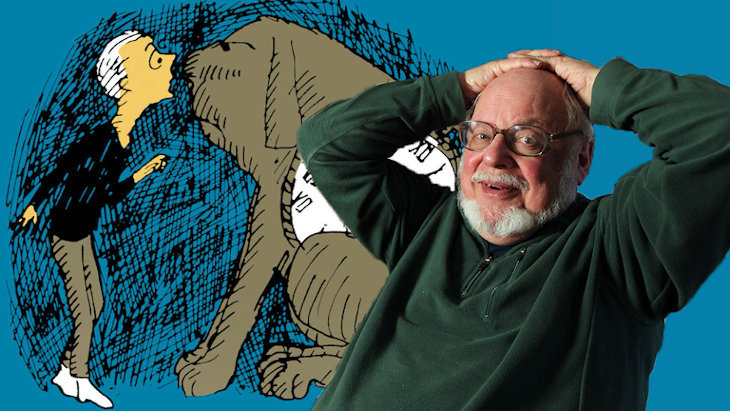

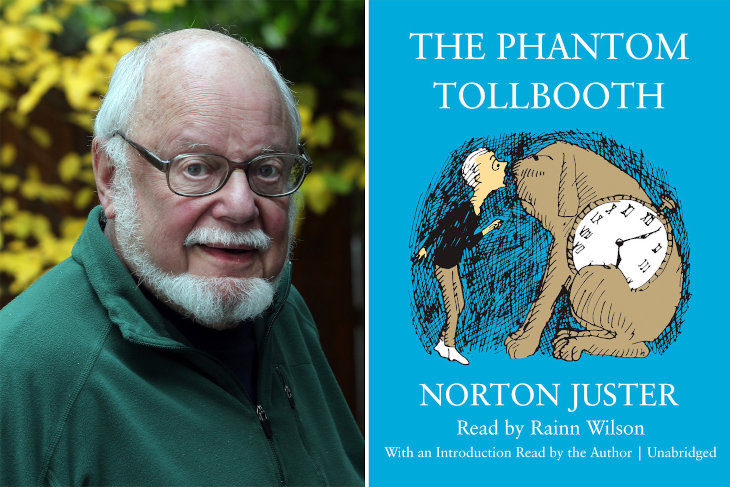

Norton Juster, the author of one of my favorite books, has died at the age of 91.

Growing up in Brooklyn in the 1930s, Norton Juster recalled living in his family’s book-lined home. His parents Samuel and Minnie were Jewish immigrants from Romania and had a large collection of Yiddish-language books. “Every day was an adventure in semantic mayhem,” he later recalled. “I just loved the language and the way the words sounded.”

Norton enjoyed writing children’s stories but for much of this professional life that took a back seat to his career as an architect. Norton eventually wrote around a dozen works; the best known is his 1961 children’s novel The Phantom Tollbooth. It’s one of my favorite books.

He got the idea of writing it while waiting for a table in a restaurant. A little boy came up to Norton. “He suddenly asked, ‘What’s the biggest number there is?’” Norton recalled. “It was a startling question. The kind that children are so good at. I asked him what he thought the biggest number was, and then told him to add one to it. He did the same to me. We continued back and forth and had a marvelous time talking about infinity and realizing that you simply couldn’t get there from here.”

“I was intrigued, and thrown back into my own childhood memories and the way I used to think about the mysteries of life,” Norton recalled. “So I started to compose what I thought would be a little story about a child’s confrontation with numbers and words and meanings and other strange concepts that are imposed on children.”

The result is an unexpectedly profound book. “There was once a boy named Milo who didn’t know what to do with himself - not just sometimes, but always,” The Phantom Tollbooth begins. Nothing seems important to Milo, and nothing interests him. In words that many of us will probably recognize from moments of frustration and hopelessness in our own lives, Milo notes “it seemed a great wonder that the world, which was so large, could sometimes feel so small and empty.”

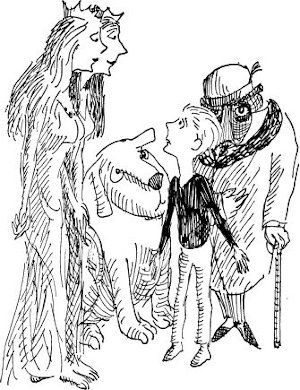

Milo comes home one day to find that a mysterious stranger has left him a magical toy: a phantom tollbooth that transports him to a wondrous world that is in desperate need of saving. Milo goes on thrilling adventures (which often involve clever wordplay and puns), picks up two helpers, and eventually restores two wise princesses - named Rhyme and Reason - to their positions mediating disputes, banishing ignorance, and once more bringing peace and happiness to the realm.

Reading The Phantom Tollbooth, I wondered if some of the Jewish wisdom that Norton Juster grew up reading in his parents’ thick Yiddish books might have influenced his writing. Perhaps Ethics of the Fathers, a Mishnaic compilation of sayings by Jewish sages, was Norton’s afternoon reading. Like so many American Jews of his generation, Norton seems to have assimilated in many ways into non-Jewish American life. Yet The Phantom Tollbooth echoes some key Jewish ideas about what our purpose in life can be.

Here are four Jewish lessons from Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth.

We've been given the most precious gift: life. Yet too often we waste our days and years, not stopping to ask ourselves how we ought to best use the precious moments we have. Jewish wisdom is full of the keen awareness of time and the fact that we ought not to waste one moment.

Norton Juster expressed this beautifully in The Phantom Tollbooth: “When they began to count all the time that was available, what with 60 seconds in a minute and 60 minutes in an hour and 24 hours in a day and 365 days in a year, it seemed as if there was much more than could ever be used. ‘If there’s so much of it, it couldn’t be very valuable,’ was the general opinion, and it soon fell into disrepute. People wasted it and even gave it away.”

Too often, life can seem to be a series of days to get through: a whole world of entertainment exists to help us pass the time.

Yet we each have a unique mission in life that we are charged with accomplishing. In The Phantom Tollbooth, Milo has to save the kingdom. In real life, we each have to find our own purpose and missions to accomplish. Time isn’t something to take for granted; it’s a finite resource that we dare not waste.

Two thousand years ago Rabbi Tarfon expressed the Jewish view of time in poetic terms: “The day is short, the task is abundant, the workers are lazy, the wage is great, and the Master of the house is insistent…” (Ethics of the Fathers, 2:20). We are those workers, each with our own abundant tasks to fulfill. Like Milo, we all have to spend our precious time wisely.

When he finally meets the wise princesses Rhyme and Reason, instead of feeling elated, Milo feels terrible. He’s made so many wrong turns and errors that it’s taken him and his friends a very long time to reach them.

“You must never feel badly about making mistakes,” explains Princess Reason, “as long as you take the trouble to learn from them. For you often learn more by being wrong for the right reasons than you do by being right for the wrong reasons.”

This is very wise advice that was first articulated four thousand years ago by King Solomon, who was said to be the wisest man who ever lived: “A righteous man falls down seven times and gets up” (Proverbs 24:16). Greatness isn’t a result of getting things right the first time we try: it’s a result of getting up over and over again, trying to do better and learning from our mistakes.

In The Phantom Tollbooth Milo and his friends get waylaid on The Island of Conclusions, a lonely place where people who jump to conclusions end up. No matter how much the people stranded there long to get back, they very rarely succeed. Jumping to conclusions is easy, but reversing those faulty conclusions is hard. After finally escaping from the island, Milo is exhausted. “But from now on I’m going to have a very good reason before I make up my mind about anything,” he says. “You can lose too much time jumping to Conclusions.”

How to avoid lazy and unconsidered thinking?

Jewish thinkers have some practical help. “Do not judge your fellow until you have reached his place,” Hillel used to say (Ethics of the Fathers, 2:5). Resisting the temptation to judge others is a key Jewish tenet. A generation after Hillel, the Jewish sage Ben Zoma described a wise man as one “who learns from every person” (ibid 4:1). Every person we meet has something to teach us. Remembering this can help prevent us from leaping to conclusions about others and their motives.

At one point in Milo’s journey he and his friends are stopped by a man who asks them to complete some simple tasks. Milo’s job is to pick up grains of sand and move them from one place to another, one by one. It’s an easy job and he doesn’t mind doing it, until he realizes with a start (and the aid of a magic staff) that doing this will take years. When he tries to leave, the man turns nasty and insists Milo continue his meaningless job.

“‘But why do only unimportant things?’ asked Milo, who suddenly remembered how much time he spent each day doing them.”

“‘Think of all the trouble it saves,’ the man explained… ‘If you only do the easy and useless jobs, you'll never have to worry about the important ones which are so difficult. You just won’t have the time. For there’s always something to do to keep you from what you really should be doing, and if it weren’t for that dreadful magic staff, you’d never know how much time you were wasting.’”

In a sense, we’re all like Milo, trapped in a cycle of mindless, unimportant jobs, and neglecting the much more important purposes and tasks that we really have to do. Yet like Milo, we each have a tool to help us. Milo has a magic staff to aid him; we have the timeless Jewish wisdom.

When Jewish leaders faced long workdays, they nevertheless made time to focus on learning Torah and remembering what is important in life, even when it was difficult to carve out the time. Rashi, one of the greatest Jewish sages, was a busy wine maker whose days were consumed with business: yet he still found the time to write reams of inspired works. Rambam, another major Jewish thinker, was a busy physician employed by a royal court. His letters describe how exhausted he was and how he hardly ever had a moment to himself. Yet he used those precious minutes to study and write some of the most important Jewish books.

“Do not say, ‘When I am free I will study,’” Hillel used to say; “for perhaps you will not become free” (Ethics of the Fathers, 2:6).

At the end of The Phantom Tollbooth, Milo returns home. The mystery stranger who gave him his phantom tollbooth takes it back. At first Milo is disappointed that he can’t return to the wondrous magical world he’s just visited, but then he realizes that far from being bleak and boring, his everyday life is full of energy and purpose. “Well, I would like to make another trip,” he says, “but I really don’t know when I’ll have the time. There’s just so much to do right here.”

My endless thanks to Norton Juster for writing a great children's book that reminds us not waste time, to remember our priorities, and to carve out space for what’s truly lasting and important.