We Were the Lucky Ones

We Were the Lucky Ones

10 min read

Noah Hertz was shot down during the Yom Kippur War in 1973. His agonizing eight-month imprisonment sparked his journey back to Judaism.

Born in 1947 in the Israeli city of Afula, Noah Hertz grew up with a love of Israel and desire to fight for his country. But Judaism wasn't something he ever seriously considered. The Yom Kippur War would change all of that.

Newly married with a two year-old daughter and another on the way, Hertz was discharged in August 1973, a month before the Yom Kippur War broke out. The pilot was called for reserve duty, leaving behind his pioneering family in their kibbutz in the Negev.

On Yom Kippur, October 6 1973, Syria and Egypt mounted a massive surprise attack on Israel’s north and southern borders, trying to catch the country off guard when most soldiers were on leave, fasting and spending the day in synagogue. Hertz recalled, “Within two hours of receiving the call, I was sitting in my airplane in my best clothes ready to go.” The serenity of Yom Kippur was shattered with the harsh reality of a war that threatened Israel’s very existence.

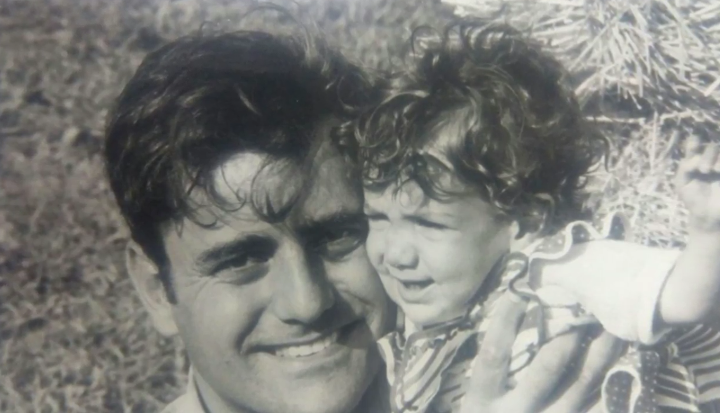

Noah Hertz in the air force before the Yom Kippur War

Noah Hertz in the air force before the Yom Kippur War

“I heard through my earpiece that hundreds of our planes had been scrambled in the air,” Hertz said, “and that many had already been shot down.”

Flying his Skyhawk Mirage, his orders were to head towards the Golan Heights where thousands of Syrian tanks, supported by airplanes and anti-aircraft batteries, had succeeded in breaking through to the southern Golan Heights. Israeli forces were bravely fighting waiting for reserve troops to arrive. “In the opening days of the war,” Hertz said, “I flew several missions. On the fourth day of the war, I was shot down.”

“It was a Thursday,” Hertz recalled. “The air force had been given orders to fight the Syrians.” Along with another pilot, his mission was to attack a base on the periphery of Damascus.

The newly married couple

The newly married couple

“We had to fly very low in order to avoid being picked up by radar."

Flying at a height of 4,500 meters, around 700 km per hour, his plane took a direct hit by a Soviet made Sa6 surface-to-air missile. “The plane began to nosedive,” he says calmly, recalling how the combination of the strike and the sudden loss of altitude caused him to lose consciousness. “I came to ten seconds before my plane would have hit the ground. I immediately hit the eject button and my parachute opened.”

The next thing Hertz remembers is opening his eyes in a Syrian hospital, weak, bruised and in incredible pain, realizing that one of his legs had been amputated.

“When I woke up, I thought of three things: I was alive, I was in enormous pain and all I wanted was to go home, back to Israel, to my wife and to my family.”

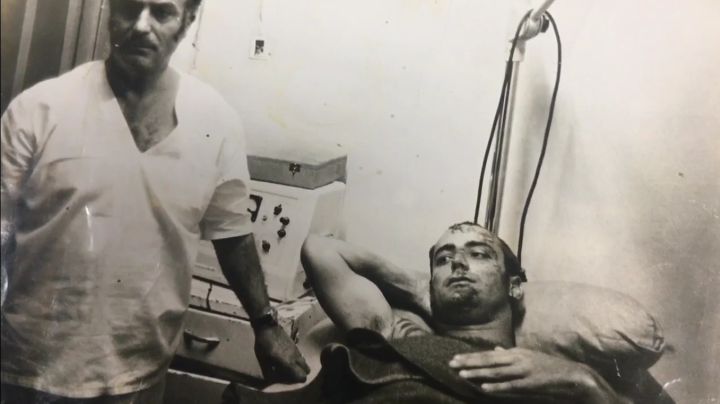

Noah Hertz waking up in Syrian hospital

Noah Hertz waking up in Syrian hospital

He stayed in hospital for five days, receiving minimal medical attention following the amputation, which he reckoned was carried out following a bad break on landing. “I had one visit from a doctor who was just walking passed me,” Hertz said. “I was given pain relief and that was it. They did the bare minimum to keep me alive.”

A few days later, Noah’s hopes were briefly raised that he was going home when he was taken from his hospital bed and loaded onto a truck. “I was sure the IDF had won the war. The pain on that journey was unimaginable but what kept me going was the belief that I was going home to my wife and my family.”

But instead Hertz went to a prison where he'd spend the next four and half months in solitary confinement. He was one of 20 IDF pilots and soldiers captured by the Syrians in that prison, each held in a tiny cell with no contact between them.

Ignoring the Geneva conventions, the Syrians treated the Israeli POWs horrifically. As the IDF advanced they found the bodies of 28 Israeli soldiers who had been blindfolded and summarily executed. The vast majority of soldiers taken prisoner by Syria had been tortured, subject to burns, electric shocks and an array of brutal punishments.

During his first week in prison, Hertz recalled how the majority of Israeli POWs were taken for interrogations. He was spared. “I was a reservist and also severely wounded. Perhaps that’s why they left me alone. What the others went through is unimaginable. Two soldiers were killed in the process.”

The first medical treatment Hertz received was to stop his bleeding after being punched in the mouth. “The medic didn’t even look at my leg,” Hertz said. “I had to take care of it myself.” Before the medic left, Hertz asked him for some basic supplies which, thankfully he was given. “I poured alcohol on the wound, tied a tourniquet and wrapped it in a bandage.”

Several days later, a medic came to his cell to check on his condition, returning every four days to change the dressing. “It was a miracle I didn’t die of an infection.”

"Despite the crushing fear of being tortured or killed," Hertz said, “the worst thing was the loneliness and not knowing when it was going to end.” For days and nights on end, he lived with barely any human contact, just alone with the thoughts of the life he had left behind in Israel.

Noah Hertz with his daughter

Noah Hertz with his daughter

“There were very hard moments that I’ll never forget, where you feel that you just can’t go on anymore.” One such moment hit him during the cold of a freezing winter when he developed an infection. “I was weak, in severe pain, with a high fever and bleeding from my wound. I was shivering and without a blanket. I was saying over and over, ‘I just can’t, I just can’t.’ I was afraid to go to sleep thinking that I wouldn’t wake up.

"I began thinking of my home, my wife and my family, everything I used to have in my life and then I burst out in tears. I left behind my wife who was about to give birth. I cried and cried and cried.”

From somewhere deep inside, he began to fight back. '"God gives you certain strength when you need it. The words of ‘Shema Yisrael’ came from the pit of my stomach. Those were my first words of prayer. 'Shema Yisrael, God help me, help me!' I cried over and over.”

Hertz fell asleep saying these words, waking up to see two Arab guards entering his cell with a mattress, blanket and a shirt. Reflecting back he quotes a line from Psalms, “When you call out to God and you really mean it, he hears.”

“I thought about so many different things,” he said. “Once, one of the guards, an Arab who had fled from Israel to Syria, told me Jews had no right to the land that he said was his." This brief exchange would eat away at him during his long hours alone

“You start to think, what is my connection to the Land of Israel? Who am I? Who are we? What is my right to the Land? My family had come from Russia, from Poland, but this Arab was saying he had been here before us. It shook me to my core. I didn't have the answers."

That proved to be a pivotal moment. “From my small cell I started to look for answers. I began to think about history beyond my parents' generation and about Abraham being told to leave the place of his birth and being promised a homeland. The more I thought, the more I realized that the education I had received fell short. I was like an orphan in history.”

After four and a half months, Noah Hertz was brought together with the other Israeli POWs. “It was hard but it was so much easier than being alone.” Among the group were several other pilots who had ejected from their planes including another three amputees.

Speaking to Israeli soldiers

Speaking to Israeli soldiers

“There had been a Jewish awakening among many of us," Hertz said. Many had prayed for the first times in their lives and were experiencing gratitude for being saved. The soldiers united, trying to give strength to each other.

“We managed to light candles from the fat from the soup,” he said, recalling how around that time they were finally allowed visits from the Red Cross. “As Seder night approached, we requested matzah and to our surprise we received some.”

With the Red Cross doing their best to ensure prisoners religious rights, the soldiers were also given a number of prayer books. “We prayed two prayer services a day with a minyan, in the morning and the afternoon. Although some of us had come from traditional families, none of us had been religious.”

“Once you take off the rank, the uniforms and you’re there in your pajamas,” Hertz said, “the soul starts to speak. There are tiny sparks inside that know the address and when these sparks grow stronger, they manage to get out.”

A week before being released, the soldiers' conditions started to improve. Hertz received new clothes and even a basic prosthetic leg from a hospital.

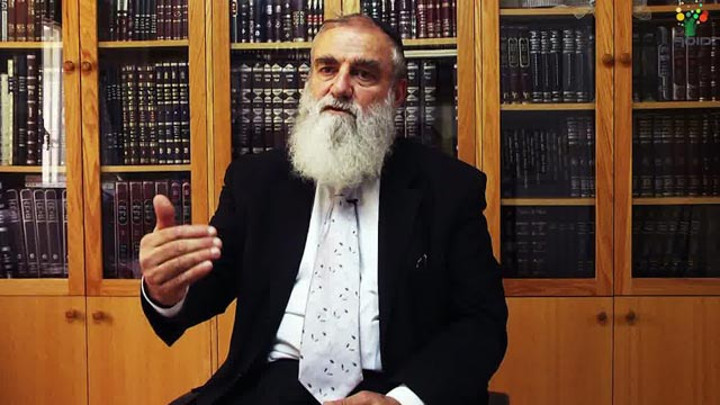

Noah Hertz

Noah Hertz

The wounded POWs were released first. “It was Shabbat,” Hertz recalled. “I felt huge feeling of joy. I was reunited with my wife and I met the baby who had been born while I was in captivity. It's hard to put into words.”

After the elation of coming home, Hertz and his wife continued the journey that began in his prison cell. “We started to ask these questions: Who are we? What values do we want to give our children? We started thinking and asking the big questions, why things happen, wars, the Holocaust, searching for answers.”

Hertz rejoined the army as an engineer and returned to the skies as a co-pilot. He and his wife started attending classes about Judaism. One of the first was a course in Jewish philosophy based on The Kuzari that explores fundamental Jewish beliefs. “It had such great depth,” Hertz said with a smile. “I yearned to know what was written in all of these other books on the shelves.”

It has been 45 years since Hertz was released. “Being a part of the Jewish People is incredible. What’s really inside is a breath-taking heritage.” Having spent decades addressing soldiers, students and communities throughout Israel, Hertz was recently awarded with an award of distinction for his service to Israel and the IDF.

“The more I think about my story,” Hertz said, “the more I see how God gave me two gifts of life, one when I was born and the second when I was taken captive. Remarkably, that was another kind of birthday.”