Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

10 min read

My journey from Eastern philosophy to traditional Judaism has taught me the importance of balancing the physical and spiritual worlds.

Dov Ber Cohen grew up in England and studied philosophy at University of Manchester. Looking for more out of life, he spent six remarkable years immersed in Eastern philosophy and tradition – earning a black belt in Tai Kwon Do on a small island off the coast of Korea; training in extreme martial arts for 16 hours a day in Shaolin, China, the world capital of Kung Fu; doing 10-day silent meditation retreats in India; hiking the Himalayas in Nepal; and trekking 750 miles around an island in Japan.

Eventually, Dov Ber made his way to Israel, where he rediscovered his Jewish roots and immersed in the study ancient Jewish wisdom. Today he is an ordained rabbi who travels the world, helping people tap into their personal potential in an empowered, conscious and joyous way. His new course, The Journey towards True Joy in Life, was just launched on Aish Academy.

Dov Ber is a popular lecturer at Aish HaTorah in Jerusalem; is educational director of Justifi’s social justice trips for Jewish students to Thailand, Peru, and Nicaragua; and is co-founder/director of Ruach Chayim: Authentic Jewish Meditation Retreats.

Dov Ber is a popular lecturer at Aish HaTorah in Jerusalem; is educational director of Justifi’s social justice trips for Jewish students to Thailand, Peru, and Nicaragua; and is co-founder/director of Ruach Chayim: Authentic Jewish Meditation Retreats.

Aish.com is privileged to share excerpts from Dov Ber's new book, Mastering Life: A Unique Guide to Jewish Enlightenment, chronicling his extraordinary stories of survival, challenge, and triumph in exotic cultures and landscapes. In this spiritual guidebook, Dov Ber shares insights into finding real meaning and joy in life; paradigm-shifting perspectives on Jewish thought and practice; and practical exercises along the path toward Jewish enlightenment.

Nine countries, one epic journey, Mastering Life transports readers on an incredible adventure around the world and, more importantly, deep inside themselves.

I left England with just nine kilograms on my back: a couple pairs of pants, some shorts, some T-shirts, underwear, and a sweater – and even that was more clothes than most of the people I was to meet on my journey had. Added to that, I had a mosquito net, a 10-meter piece of string, a head torch, writing pad, padlock, diary, mosquito spray, Swiss Army knife, toothbrush and toothpaste, painkillers, antiseptic cream, and a couple of books.

The poor man sleeps well. He has nothing to lose.

There's a saying in India, "The poor man sleeps well." He has nothing to lose. He doesn't have to worry about his car getting scratched or his stock going down. Similarly, living out of a backpack leaves you little choice: you can only carry what you really need, and it is incredibly liberating to realize just how little one needs to get by. Having limited "stuff" taught me to really value, take care of, and appreciate everything I had, as well as learn a lot about myself and what was important to me.

My ten-meter piece of string was essential for putting up the mosquito net, hanging laundry up to dry, building shelters, and repairing my backpack. I valued it immensely and rolled it up and packed it away carefully each time I moved on. In Asia, insect repellent is indispensable if you want to have any peace of mind, whether walking through a jungle, meditating on a mountain, or sitting around a fire on the beach. I guess I'd add on to the Indian saying – "The poor man sleeps well... as long as he has a mosquito net."

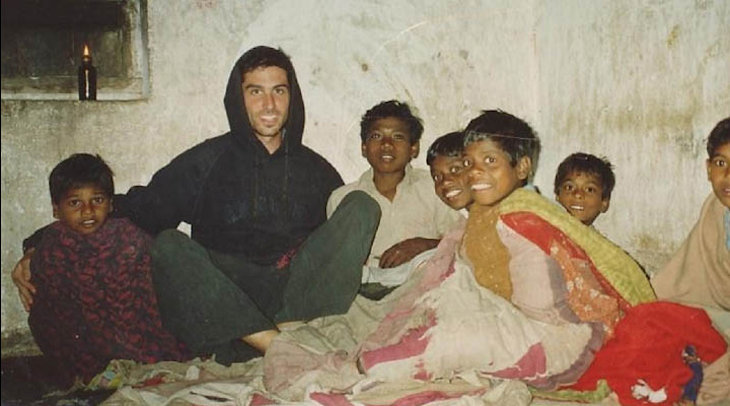

Dov Ber at the Baghar Orphanage in India.

Dov Ber at the Baghar Orphanage in India.

To some extent, material possessions certainly increase happiness levels. If you are homeless and cold, acquiring a small apartment and getting some hot food will certainly make you happier. If you have to ride your bike up lots of hills to get home from work after a hard day, buying an electric bike will give you great pleasure.

Yet the truth is that once we have the basics, adding material possessions will never actually fulfill our emotional, intellectual and spiritual needs. In fact, quite the opposite is true. Research has shown that this focus is what causes most mental and emotional problems, because wanting more than we need and comparing ourselves to others means we will never feel fulfilled, satisfied, and significant. One report shows that until an income level of $75,000 per year, happiness levels increase, but from then on, having more money makes absolutely no difference…

Beyond the basics, material possessions will not fulfill our emotional, intellectual and spiritual needs.

It's important to note that according to Jewish teachings, there is nothing wrong with being rich and having nice things. If you study and work hard, you deserve possessions to enjoy, and it is noble to provide for your family. Some philosophies teach that we shouldn't have money – it corrupts you, makes you greedy, causes worry, makes you arrogant, and makes you partake of things you shouldn't partake of. Although, unfortunately, this is often the case, it doesn't have to be like that. Many of our greatest sages (including Moses and Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi) were very wealthy. Many mitzvot, such as charity, hosting guests, and redeeming captives are accomplished with money, so the money itself is clearly not the problem.

The real problem comes when people start making money their top value at the expense of other people and the world around them, defining themselves and their self-worth by it. The World Watch Institute reports that the amount of money spent annually in America on cosmetics is eight billion dollars, and that an extra nine billion dollars a year would provide clean water and sanitation to all people in all developing nations throughout the world. Consumerism is consuming us and the world around us.

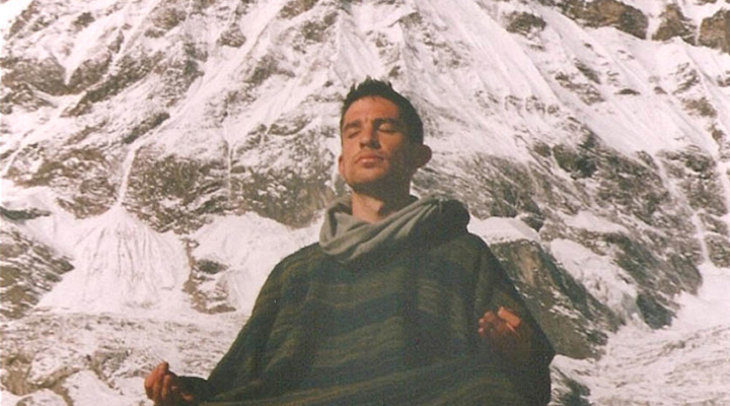

Dov Ber meditating at Anapurna Mountain Base Camp in Nepal.

Dov Ber meditating at Anapurna Mountain Base Camp in Nepal.

Success, in Torah terms, is not based on what you have, it's based on who you are; how much you have perfected yourself in thought, speech, and action; and how much you are giving to those around you. When imagining a successful person, what should come to mind is not someone with lots of money. A successful person is a tzaddik – someone with refined character traits, a good attitude and disposition; someone who is there for others and always does the right thing.

We all know this intuitively because at every funeral, the eulogies focus on good character traits and how much the person contributed to the world around them, not on how many cars they had and how much money they made. What we are aiming for, how we get self-respect, what creates a meaningful life, and what dictates how much joy we have is not how much we make but how much we give. It's not about how we've prospered but rather how much we've grown.

It's not about looking good, it's about being good. Healthy self-esteem comes from respecting ourselves for how much we've grown and contributed, not what others think of us based on superficial values. Reaching success in these terms is the key to living meaningful, constructive, and happy lives.

Hindu philosophy teaches that this world is maya, an illusion. Not unlike the Buddhist idea of detachment, these philosophies in general expound that the way to achieve moksha (liberation) is to renounce attachment to the physical world, freeing ourselves from the shackles of the body and ego, which pull us down, control us, and ultimately keep us from connecting to our Divine essence.

Like Buddhist monks, Hindu sannyasins don't get married, they refrain from physical intimacy, generally eat as little as is needed to sustain the body, renounce all worldly pleasures, have no money and very few possessions, and live ascetic lifestyles – free from the stresses of everyday life and able to concentrate on meditation, yoga, and other spiritual practices.

Judaism teaches to balance and integrate the physical and spiritual aspects.

Whereas Eastern philosophies in general teach us that to be spiritual we have to detach from the world, and the West tends toward materialism and physicality, Judaism teaches that we need to balance and integrate the physical and the spiritual aspects of ourselves – our body and our soul. Our Sages teach that rather than being a physical being (a body) that is trying to have a spiritual experience and connect to our soul, we are in fact spiritual beings (soul) that have a body, the aim of which is to use physicality as a tool to becoming spiritual.

At first glance, as is very often the case, it seems that Jewish sources actually teach two opposing ideas in this area.

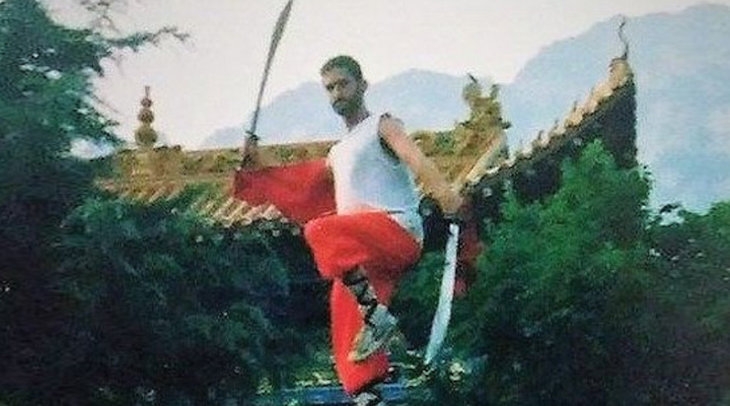

Shaolin kung fu training in China.

Shaolin kung fu training in China.

On the one hand, we learn that God wants us to partake fully in and enjoy the physical pleasures of the world. Two of the first things Hashem says to Adam and Eve are "Be fruitful and multiply" and "Eat of all the fruit in the garden." Our festivals are accompanied by lavish meals, we are meant to have special clothes for special occasions, and Purim takes indulgence in physicality to the next level.

The Talmud teaches that a nazir, one who refrains from drinking wine, must bring a sin offering at the completion of his term because we aren't meant to separate from worldly pleasures. The Jerusalem Talmud even suggests that at the end of our time here we'll have to answer for not enjoying the physical pleasures of the world. So we see that Judaism teaches that Hashem, like any loving father, wants His kids to enjoy some ice cream once in a while…

We use physicality as a tool to connect to greater spiritual heights.

Judaism teaches that the ultimate spiritual path is not to shun the world and remove ourselves from it, nor to get lost in materialistic hedonistic pursuits. Rather, in order to be on a truly high spiritual level, we need to be very fully in this world, just in such a tremendously mindful way that we actually use physicality as a tool to become connected to the greatest spiritual heights.

How is this achieved? Let's take eating as an example. We love eating, and a major part of almost every festival and holy day is the seudat mitzvah (the mitzvah meal). However, before we put any food in our mouth, we make sure it's kosher; if it's dairy, we work out when we last ate meat; we say a specific blessing; we eat consciously (or at least are meant to); we share words of Torah during the meal; and we conclude with a specific blessing. In this way, we turn eating itself into a spiritual practice. The same goes for all other permitted physical pleasures in the world.

Physical pleasure for its own sake is egotistical, temporary, and disconnects us from spirituality. Pleasure as the reward for or consequence of yearning to uplift the world and bring God-consciousness into all mundane activities is the greatest, most authentic physical pleasure there is.

Rabbi Dov Ber Cohen's new course, The Journey towards True Joy in Life, has just been launched at Aish Academy. Discover how to become truly happy without relying on others, increase your meaning in life and get practical tools on attaining true happiness and inner peace. Click here to join.

For over 45 years Aish has helped millions of Jews around the world connect with their roots through timeless Jewish wisdom.

We’re not finished yet.

Join our $3M matching campaign and help 3 million more Jews connect to the meaning of their Jewish heritage.