Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

13 min read

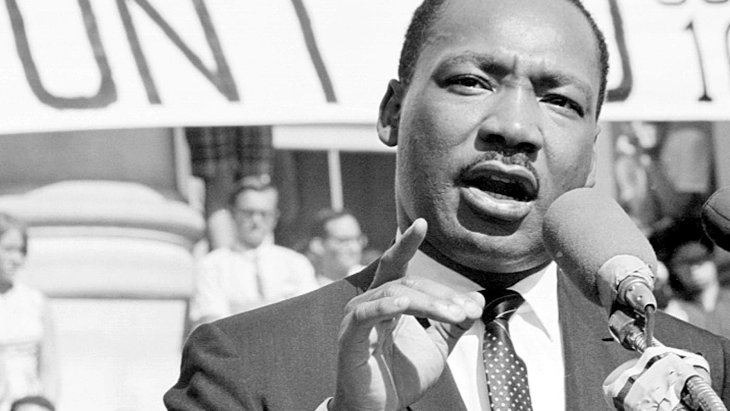

How Martin Luther King’s commitment to his roots inspired me to return to my own.

We were relaxing in our tiny rented apartment when we heard a screech outside. Headlights were shining out in front; a couple of rednecks had stopped their car, and they began pumping a cascade of bullets through our kitchen window. We ducked down behind the sofa as the bullets continued to shower, blowing out the glass.

The shooting stopped, and we heard the car accelerate. But we didn’t get up so fast. We stayed down there a few more minutes until our heart rates had slowed enough for us to stand up. The bullets had broken dishes, poked holes in the thin sheetrock, and decorated the linoleum. None had hit us, but we had gotten the message.

It was a humid South Carolina summer night in 1965, the kind of humidity that plays with your brain and senses. Peter and I were drunk from the heat and looking to break out of the doldrums. We were two young college students who were game for a little adventure. Perhaps we were a bit foolish. No, we were really foolish. And that’s why we decided that instead of sitting in that little apartment in the heat, we’d go to the Ku Klux Klan meeting at a farm nearby in Orangeburg.

In those days, Orangeburg was a hotbed of the Confederacy and white supremacist hatred. We thought it would be cool to eavesdrop on what “the Klan” was doing. Meetings were open to the public, after all, and we were young white boys, so what could be dangerous?

We tried to blend in and cheer when the other people at the meeting cheered, and boo when they booed. Then the KKK leaders, wearing white robes with hoods that covered their faces, urged the participants to raise funds to help the cause. We decided to contribute as well and checked our pockets for loose change. What we hadn’t realized, though, was that there were a few buttons from SCOPE in our pockets, and those made their way into the collection box.

The atmosphere was explosive. We tried to put on angry expressions and mimic the sentiments of the crowd, but inside we were quaking with fear.

SCOPE stood for the Summer Community Organization and Political Education program. As a young, idealistic college student eager to make a difference, I had been recruited to join SCOPE earlier that summer by Professor James Shenton, then one of the heads of the history department at Columbia University. The organization ran voter registration drives, held information sessions, and galvanized other community organization efforts. The project was under the leadership of a young, idealistic black preacher, Dr. Martin Luther King, who would be brutally assassinated three years later for daring to speak his mind in an era of racism and intolerance.

It didn’t take long for furious shouts to ring out. “Who put these buttons here?” someone shouted, wagging his finger at the crowd. The locals seethed with rage. “We’re gonna get you!” The atmosphere was explosive. Peter and I tried to put on angry expressions and mimic the sentiments of the crowd, but inside we were quaking with fear.

Fortunately, no one connected us with the buttons, or we would have been lynched on the spot. When we saw that the crowd was beginning to disperse, we quickly escaped from that boiling room, grateful to get away. But our relief was premature.

I was born in New England in the mid-1940s and was raised in a traditional “Conservadox” home in Detroit, Michigan. During the summers I went to Camp Ramah, where I was first a camper, then a counselor. I have always enjoyed singing and playing folk music, and I used to entertain the campers on humid summer nights. After graduating high school, I went to college to study history, which has always fascinated me.

In 1966, I graduated Columbia University and the Jewish Theological Seminary with an MA in history; later I received a Juris Doctorate (JD) from Wayne State University and a master’s in Near Eastern studies from the University of Michigan. But my interest in academia took a back seat to my true passion, which was community activism. This was during the roaring ’60s, when the civil rights movement swept across America, and many Jewish boys like myself were caught up in the excitement. All humans are created equal, and that included African Americans, who were finally granted equal rights when the Voting Rights Act was passed in August of 1965.

That was the summer when Professor Shenton recruited me and Peter Geffen, a college friend, to join SCOPE. We would be spending the summer in Orangeburg, South Carolina, but first we were sent to Atlanta for orientation. It was there that I met Dr. King. He was in the company of other prominent civil rights leaders, including Bayard Rustin, Hosea Williams, and Andrew Young.

Although the encounter took place decades ago, I remember it as clearly as if it were yesterday. Dr. King was a powerful, charismatic figure, filled with a sense of responsibility. He spoke softly at times, but when he opened his mouth, everyone listened carefully. He had an aura that was hard to describe.

The orientation was very exciting, with speakers from all over the country talking about responsibility, brotherhood, and the rights of every human being. Although the orientation was comprehensive, no one thought to mention that we were heading into hostile territory and that our lives might be at risk. We were young and motivated, and fear was the last thing on our minds.

Rabbi Abraham Heschel, Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington Cemetery, Feb. 6, 1968.

Rabbi Abraham Heschel, Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington Cemetery, Feb. 6, 1968.

During a break in the orientation, Peter and I were invited backstage, where we were finally introduced to Dr. King. It felt very natural, as though I were meeting a friendly uncle or someone I’d known for years. One of the organizers suggested we take a picture. Someone there had a Polaroid camera, which was the latest gadget in those days. A picture was snapped and Dr. King autographed it, writing, “Best wishes, thanks for your help.”

Today this autographed picture might be worth a considerable sum, but I no longer have it. Unfortunately, when we mailed it to a Rochester photo shop to have it enlarged, we received the enlarged photo with the autograph superimposed on the front, but the original, with Dr. King’s autograph on the back, was never returned.

We finally made our way to South Carolina, where thousands of African American families lived in impoverished communities. Practically the only white people who set foot inside their homes were the sheriff and the tax collector, so they were naturally wary of white people.

Although I was white and Jewish, I became very close to members of the black community and was welcomed into their homes. Perhaps it was my genuine desire to bridge the gap, to understand their struggles and concerns. I would speak to them on Sunday, when they returned from church, delivering the poignant message that all men were created equal and that Dr. King would lead them to freedom. After my speech, they would all reply with a single word: “Hallelujah!”

During the summer I was appointed chairman of SCOPE, a position that put me in the cross hairs. But I was oblivious to this reality – until the night my window was shattered with bullet holes.

“If I ever see you here again, both of you and your car will end up at the bottom of one of those swamps.”

If you’re wondering why we didn’t call the police, let me explain. During the 1960s, many of the cops in the south were white supremacists who were in cahoots with the KKK. In fact, just a couple of months later, I had another incident that shook me up.

While driving late at night in a swampy region of South Carolina with a young black activist in the passenger seat, we were pulled over by a white cop. After carefully inspecting our car and noticing the civil rights literature, he issued a warning. “I know who you are,” he said with obvious hatred. “If I ever see you here again, both of you and your car will end up at the bottom of one of those swamps.”

Rabbi Moshe (Micky) Shur

Rabbi Moshe (Micky) Shur

It wasn’t just an empty threat. A year earlier, in 1964, three prominent civil rights activists had disappeared one night in this area. Their bodies were found a couple of years later at the bottom of a swamp.

In fact, the famous crime thriller of 1988, Mississippi Burning, was based on the true story of several civil rights activists who disappeared in a small Mississippi town and whose murder was covered up by the local authorities. It is based on incidents that occurred during the years I was active in the civil rights movement.

Peter and I witnessed the aftermath of the KKK burning down a historic church, and we participated in a rowdy courthouse demonstration. I was arrested during another demonstration, dragged off in handcuffs by the state police, and my picture was in all the papers.

All of this activity made my parents very nervous. They were terrified for my safety. Seeing my picture in the papers made them realize the full extent of what I was involved in, and they drove down to the South in 1966 during their summer vacation to bring me back home. I protested, saying that I was happy where I was, but they tempted me with a trip to Israel, a place I had never visited. I agreed to go.

This was before the Six-Day War, when idealism was at its peak. Israel was under attack by its enemies, and most of the country was off limits. I landed at Ben Gurion, went to a kibbutz and did manual labor for a few months, and fell in love with the land.

I credit Dr. King’s example to my eventual decision to become an observant Jew and make move to Israel.

After that pivotal summer, I returned home to finish my degrees, but eventually I decided to make aliyah. The assassination of Dr. King in 1968 and the ideals he stood for had made a huge impression on me. I realized that everyone needs to live with meaning and purpose, to make a difference in this world.

In fact, I credit Dr. King’s example to my eventual decision to become an observant Jew and make move to Israel. Having witnessed up close his idealism and commitment to his roots, I was inspired to live with meaning and purpose, and I wanted to make a difference in this world, so I chose to help the African American community, and then later my fellow Jews.

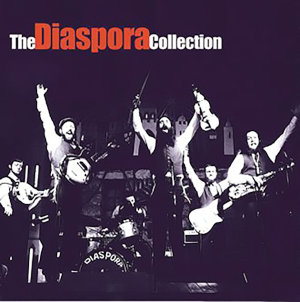

In 1974, I settled in Israel where I joined the Diaspora Yeshiva, the renowned baal teshuvah yeshivah founded in 1967 by Rav Mordechai Goldstein. The baal teshuvah movement exploded shortly after the Six-Day War in June of ’67, when tens of thousands of young college students, inspired by Israel’s victory, began flocking to the Holy Land to learn about their roots. The Religious Affairs Ministry leased a few buildings on Har Zion to the yeshivah, and also built the Chamber of the Holocaust nearby.

The Diaspora Yeshiva Band

The Diaspora Yeshiva Band

The yeshivah was the birthplace of the world-renowned Diaspora Band, and I was one of its founders. In existence from 1975 to 1983, the band infused rock and bluegrass music with Jewish lyrics, creating a style of music we called "Chassidic Rock." I composed some of its iconic songs, including “Ivdu” and “Hafachta Mispedi.”

Rav Goldstein allowed the students to keep their long hippie hairstyles and colorful attire, and to play music expressing the stirrings of their souls. This was the era of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, when a young generation expressed its angst and yearning through song.

At first, we were just a group of musically-inclined students who sat on the ground strumming our guitars and singing together late into the night during a kumzits, especially on Motzaei Shabbos. Soon I purchased a sound system at a discounted price from a wealthy patron, and around 1974, the troupe coalesced into a real band.

We originally had 15 members, with a core of five or six who continued for several years. They were bandleader and singer-songwriter Avraham Rosenblum on lead guitar; singer-songwriter Benzion Solomon on fiddle and banjo; Simcha Abramson on saxophone and clarinet; Ruby Harris on violin, mandolin, guitar, and harmonica; Adam Wexler on bass; and Gedalia Goldstein on drums. I was a vocalist and ran the sound system. The band became a sensation on college campuses around the world, and it became famous for its sold-out Motzaei Shabbos concerts at Assaf’s Cave at Har Tzion, the site of King David's burial site where the Diaspora Yeshiva was located.

We would get together for what we called a “jam session” and just play from the heart. Benzion Solomon was the only member of the band who had a degree in music and who could read music and do arrangements. The rest of us improvised, playing by ear.

I got married in Israel to my wife, Shoshana. We moved to the States in 1977, where I taught and did outreach at the University of Virginia. Then we went to New York and I joined Queens College, where I have been a faculty member and the executive director of its Hillel program since 1979, over 40 years.

Today I am an adjunct professor of history and a senior associate for the Center for Jewish Studies. I teach a Jewish history course, as well as a course called “Introduction to Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalah.” Over the years I have produced six music CDs, one of them in collaboration with my son, called A Shur Thing (available on Spotify).

Among college students, I am best known for my annual five-day summer tour. It’s called “In the Footsteps of Dr. King,” and it takes college students to the Deep South, including Atlanta, Georgia, and Selma, Montgomery, and Birmingham in Alabama. We visit a memorial to the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of African American military pilots who fought valiantly during World War II.

When I lead tours to the South, I am able to connect to these college students who want to learn more about what Dr. King represented. I show them a picture of myself with Dr. King and talk about how he inspired me to find my own roots.