Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

7 min read

What happens when the majority isn't right?

I was in eighth grade and my classmate Kevin came over to me. He told me to sit down because he had a great joke to tell me. A few of the guys were smiling.

Two polar bears are sitting in a bathtub. The first one says, “Pass the soap.”

One of the onlookers started cracking up. As he left our little group, he kept laughing and repeating the words, “I can’t, I can’t…”

Kevin looked at me and finished the joke.

So again, two polar bears are sitting in a bathtub. The first one says, “Pass the soap.” And then … the second one says … [here Kevin had to hold himself in] … the second one says, “No soap, radio!”

At this point, the entire group gathered around started losing it. I don’t mean little chuckles. I mean loud, uproarious belly laughter.

I was the only person who didn’t get the joke. And they were starting to notice. So I started laughing too. This made everyone else laugh even more.

Only later did I realize why.

Kevin and the guys had set me up with a non-joke, a punch line lacking any humor at all. The whole point was to put me on the spot. They wanted to see if I would laugh along with the group just to fit in, despite having nothing funny to laugh at.

The joke was on me. And I fell for it.

The Asch Paradigm

A more scientific version of the now-famous “No Soap, Radio” joke was conducted by psychologist Solomon Asch. His experiments, published in 1953, have become famous for demonstrating the amazing power of conformity in groups.

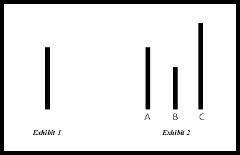

Groups of eight students were invited to participate in vision tests. They were to look at two cards. One card had three lines of varying lengths. The other had one line, which matched the length of one of the lines on the other card. The stated goal was to check students’ vision and ask them to identify which of the three lines matched the length of the line on the other card. The differences in line length were both significant and obvious.

In truth, all of the participating students – with one exception in each session – were “in on the joke.” The “fake” students would, by prior agreement, give wrong answers and identify the wrong line. Dr. Asch was not interested in testing students’ vision. The goal was to see how the one “real” test participant would react: would he stand up for what his eyes clearly told him? Or would he change his answer in order to avoid sticking out and looking foolish?

The results were astounding. Seventy-five percent agreed with the incorrect answers at least once. The more “fake” participants there were, the higher the proportion of incorrect answers given by the “real” participant. The more uniform the “fake” participants were in their incorrect answers, the higher the proportion of incorrect answers given by the “real” participant.

To avoid standing out, a large percentage of people go along with an incorrect majority.

Dr. Asch’s experiments taught that in order to avoid standing out, a large percentage of people will go along with an incorrect majority, even when the majority’s mistake seems very obvious.

But a question always lingered about the Asch Paradigm. Did the “real” participants choose to lie to avoid potential embarrassment, or did they somehow come to really agree with the “fake” participants’ (incorrect) answers?

In 2005, Dr. Gregory Berns, a neuroscientist from Emory University in Atlanta, conducted Asch-type experiments while monitoring the brain’s activity using M.R.I. scanners. His findings were later published in the Biological Psychiatry journal.

Dr. Berns’ approach was based on an amazing realization. If subjects were consciously lying, the M.R.I. should show activity and change in the frontal areas of the brain that deal with conscious decision-making and conflict resolution. If, on the other hand, the subjects somehow came to believe the group’s (incorrect) answers, activity and changes should appear in the back areas of the brain that deal with vision and objective spatial perception.

Confirming the Asch paradigm once again, Dr. Berns and his team found that “real” participants often agreed with the group’s obviously incorrect answers.

The M.R.I. scans were even more revealing. Scans of “real” participants who conformed to the group’s incorrect answers revealed activity in areas of the brain devoted to vision and objective perception. No activity was recorded in areas devoted to decision-making and conflict resolution.

In other words, when faced with a majority opinion that is clearly contrary to physical reality, almost half of the population will not only go along with the majority, but will come to actually believe that the majority is right.

Swimming Upstream

It is understandable to prefer going along with the flow. Nobody wants to stand out. It is lonely. It is uncomfortable. Occasionally, it can be dangerous. There is safety in numbers. And comfort. Life isn’t easy. Why make it harder by disagreeing with the majority?

On the other hand, sometimes the Emperor really has no clothes.

Going along with the majority is problematic because of its inherent falsehood. Furthermore, it also leads down a terrible path. Societal norms have often caused terrible tragedies. Majorities in many societies of the past practiced human sacrifice. The ancient Greeks practiced infanticide if the baby was deformed, dull, or, often, female. The ancient Romans’ favorite societal pastime was watching starved animals, or gladiators, attack, maim, and kill innocent women and children whose great offense was being born in foreign lands. More recently, Hitler was elected in a democratic election by the German electorate. And terrorists enjoy wide support in certain countries. Is the majority always right?

Tool of Resistance

Abraham was a “Hebrew,” an English version of the Bible’s term “Ivri,” which refers to the fact that he was “oh-ver” – he had crossed to the other side. He stood on one side of a great philosophical debate (monotheism versus idolatry) and held his ground, even though the whole world was on the other side. We are a nation of Hebrews – we stand up for truth. Russian anthropologist Michael Chlenov perhaps put it best when he wrote that, “Judaism is a tool of resistance.” Throughout history, the presence of a distinct Jewish community has always been a clear challenge to absolutist claims and majority rule.

Being Jewish means rejecting the status quo.

The Assyrians worshipped idols and bid us to do the same. We refused and, directly and indirectly, reminded the world that the Assyrian view was not the only way of understanding life.

The Greeks admired the human body above all else, while we taught that the soul is supreme.

Roman society was brutal (gladiators versus innocent men and women) and shockingly sexualized (pedophilia was widely practiced). We were examples of kindness and monogamy.

Throughout history, our commitment to our beliefs has challenged the conventional wisdom. This has often provoked no little antagonism. Yet we have stood firm against the winds. We have opposed and continue to oppose idol worship, rampant materialism, and consumerism. We strive to reject falsehood, evil, and immorality.

Being Jewish is a wonderful privilege and opportunity. It means being committed to seeking the truth. To admiring and developing knowledge and wisdom. It means focusing on a better future, and working towards it. It means standing up against the world’s false gods – whatever they may be in any given generation – and rejecting the status quo as acceptable.

Excerpted from Doron Kornbluth's new book, Why Be Jewish? Knowledge and Inspiration for Jews of Today.