You Know More Hebrew Words Than You Think

You Know More Hebrew Words Than You Think

8 min read

Survivors testify about an epic Seder held in underground bunkers as the Nazis sought to liquidate the last Jews of Warsaw Ghetto.

In April 1943, at the height of the Final Solution, with the sounds of tank rounds and gunfire around them, the last remaining Jews of Warsaw huddled together in bunkers under their besieged ghetto to live their final hours as proud Jews, reading the Passover Haggadah. In the hours that followed, they would rise up in one of history’s most iconic feats of resistance.

The handful of Jews who survived the Nazi’s final onslaught on Warsaw, once a major center of Jewish life, have this Seder night more than any other etched in the memories as a testament to Passover’s powerful calling to connect to family, history, tradition and hope.

Every Passover during the Nazi occupation of Warsaw, which began in October 1939, the Jewish community did its best to celebrate the holiday. Even after being forced into a ghetto measuring just 2.5% of the city, subject to terrible starvation and disease, additional non-leavened foods were smuggled into the ghetto in the weeks before Passover. Several matzah factories were set up, ensuring the community, at its height numbering almost half a million, could eat the bread of freedom Seder night. Despite the hunger, typhus and dysentery, Jewish life in the ghetto continued.

Matzah being distributed in the Warsaw Ghetto

Matzah being distributed in the Warsaw Ghetto

Passover in April 1943 would be the last for the Jews of Warsaw Ghetto, although by then the community was already unrecognizable. Almost a year earlier Adam Czierniakow, the Head of the Judenrat, the Jewish council appointed by the Nazis, had committed suicide after hearing of the Nazis plans, leaving a note to his wife that he “Would not be the hangman of Israel’s children.” The Nazis had since begun a terrifying program of ‘liquidation’ deporting between 5,000 and 6,000 Jews daily to the Treblinka death camp where they were murdered within an hour of their arrival.

On January 18 1943, the Nazis attempted to take another 8,000 Jews but this time members of a newly formed Jewish resistance fired shots at the SS guards and the Nazis rethought their plans, bolstering their military presence, delaying the final liquidation of ghetto to Passover which would fall in three months’ time.

On the 18th of April 1943, when news arrived that the Germans had stationed an army in Warsaw ready to empty the ghetto, members of the underground resistance movements went into high alert. While the rooftops were stationed with Jews keeping track of the enemy’s every move, below the ghetto, Jews were busy embracing the story of the exodus from Egypt as a symbol of their own fight for dignity, pride and hope.

Roma Frey was 24 that Passover, recalling how she and her family had tried their best to make the basement as nice as possible for the holiday, “We tried to put the candles on the table, and a white table cloth,” she adds, “the table was made of a wooden board resting on a few things underneath.”

A hidden matzah factory

A hidden matzah factory

Surviving the Holocaust and moving to Melbourne Australia after the war she added. “We acknowledged to ourselves and to God and to ourselves that we want to keep the traditions. That’s what we felt in our hearts, we remembered our grandfathers, the hard times, slavery and our slavery, and here we have, hardly a hope to survive even just one day or night.”

With families decimated by the deportations, the remnant Jews came together, relying on those who knew the Haggadah by heart to lead them. Many flocked to the home of the 60-year-old venerated Rabbi Eliezer Yitzchak Meisel, who had left his hometown of Lodz along with his followers years earlier when the Nazis invaded. In Warsaw he had become immediately involved in maintaining religious life amid the hardships; it was in his basement that many of the Jews active in the resistance joined for the Passover Seder.

Tuvia Borzykowski was 29 at the time. “No one slept that night,” he recalled. “The moon was full and the night was unusually bright.” Along with the other fighters he joined Rabbi Meisels for the Seder.

Tuvia Borzykowski

Tuvia Borzykowski

“Amidst this destruction, the table in the center of the room looked incongruous with glasses filled with wine, with the family seated around, the rabbi reading the Haggadah.” Throughout the night, despite the increasing sounds of enemy fire, Tuvia and the other fighters held fast, engrossed in the retelling of the Jewish people’s redemption from Egypt. He recalled, “The Rabbi’s reading was punctuated by explosions and the rattling of machine-guns; the faces of the family around the table were lit by the red light from the burning buildings nearby.”

“Now is a good time to die,” Rabbi Meisels said, buoyed by the feeling of pride, courage and faith, as he blessed one of the fighters who came to deliver a report. He died later that night in the flames of the ghetto. Tuvia Borzykowski survived the war and helped establish Kibbutz of Ghetto Fighters near Akko. He is one of several fighters who testified about the Passover Seder they took part in as the uprising began.

Born in Warsaw, Itzchak Milchberg was the leader of a group of Jewish boys posing as non-Jews outside the Ghetto walls, selling cigarettes on the black market to survive. On the eve of Passover in 1943 he was just 12 years old but wise beyond his years. He had seen his father shot before his eyes, his mother and two sisters had already been deported and the only family he had left was an uncle named Fievel who was still in the ghetto.

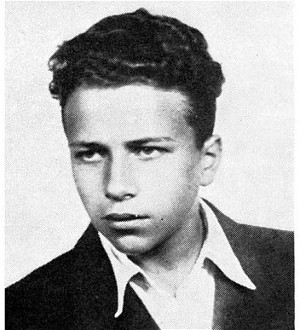

Itzchak Milchberg , age 13, a year after the uprising

Itzchak Milchberg , age 13, a year after the uprising

When rumors spread that the Nazis were planning their final deportations, he returned to the ghetto to be with his uncle for Passover. “I had never missed a Seder,” he said. “It was in my blood.”

With the sound of shooting around him, he entered his uncle’s candle lit bunker where 60 people were crowded. “The building was shaking,” he said, “People were crying.” His uncle Feivel embraced him in Yiddish, “Ir vet firn di seder mit mir - You’ll perform the Seder with me.” However some were too distressed to think about running a Seder. He recalls people crying, “God led us out of Egypt. Nobody killed us. Here, they are murdering us.”

Pulling him close, whispering into his ear, Feivel told his nephew, “You may die, but if you die, you’ll die as a Jew. If we live, we live as Jews.” He added, “If you live, you’ll tell your children and grandchildren about this.”

The Seder began. Feivel Milchberg had managed to organize matzah, “I don’t know how he got it,” Itzchak recalls, although he remembers there were no bitter herbs, “There was plenty of bitterness already,” he says.

Together with his uncle he read the Haggadah from memory and soon most of the bunker joined in. “We did most of the prayers by heart,” he says. “The Seder went very, very late.”

He left the ghetto in the early hours of the morning through the sewer system, risking his life as he had done to be there in the first place. In the days that followed he worked as a runner, smuggling arms through the sewers to the Jewish fighters until he was caught on the sixth day of the Uprising. He would later jump from a train taking him to Treblinka and survive the Holocaust thanks to a Catholic family in Warsaw. After the war, he moved to Canada, raised a family of his own and made good in his promise to his uncle to tell his children and grandchildren about that Seder night he had led with his uncle in 1943.

As promised a large SS unit entered the ghetto attempting to deport the remaining Jews to their deaths. But they were met instead by fierce fighting from the Jewish resistance and a barrage of Molotov cocktails, grenades and gun-fire. With renewed strength and pride, this fledgling Jewish fighting force killed 13 Nazis, wounded many more and sent them panicked, retreating out of the ghetto. They held out for almost a month as the Germans set to work painstakingly burning each building in the ghetto to the ground. 13,000 Jews died in the fighting and the flames while thousands more were arrested and deported to the east.

The last Jews leaving the ghetto after the uprising

The last Jews leaving the ghetto after the uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising will always be remembered as the greatest physical resistance throughout the Second World War, inspiring underground movements and partisan units across Nazi occupied Europe. Spiritually, the Seder service that took place below its charred streets that night can continue to inspire generations of Jews who refused to be broken even at the darkest of times.