Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

7 min read

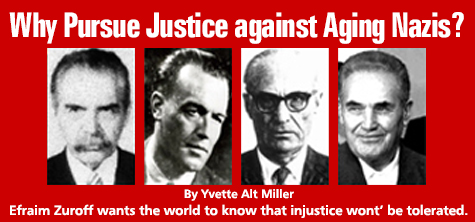

Efraim Zuroff wants the world to know that injustice won't be tolerated.

On June 18, 2013, Hungary charged Laszlo Csatary, a 98-year-old former concentration camp commander, with assisting in the murder of over 15,000 Jews during World War II. (The announcement came days after German and Polish officials said they would review evidence that a Minnesota man, Michael Karkoc, was a former concentration camp commander and might be indicted on war crimes, too.)

Laszlo Csatary was known for not only overseeing Jews’ deportations and deaths, but also for torturing and murdering Jewish prisoners personally. Instead of being arrested and prosecuted after the War, however, Csatary managed to get papers to emigrate to Canada, where he lived undisturbed for decades.

My recent article about the startling roles the Red Cross and Vatican played in helping Nazi war criminals like Csatary evade justice after World War II generated lots of reader comments. While many applauded efforts to bring these escaped Nazis to justice today, others wondered if perhaps it was too late. Some doubted the value of prosecuting Nazis at all. Maybe, they asked, Nazis should be left to divine justice instead of human courts?

As the number of Nazi war criminals dwindles, Laszlo Csatary’s trial – and, if enough evidence is found, Michael Karkoc’s too – will be among the very final opportunities the world has to bring justice to criminals from this era.

Efraim Zuroff

Efraim Zuroff

How does the man most responsible for bringing Csatary and dozens of other Nazis to justice – Efraim Zuroff, Director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Israel Office – explain why it’s important to pursue justice against Nazi war criminals, even at this late date? In a world where many question whether we ought to be pursuing the last of the surviving Nazi war criminals, how would Nazi-hunter Zuroff justify his tireless life’s work?

Speaking with Aish.com on the day Csatary was charged, Efriam Zuroff sounded elated.

He’d worked on the Csatary case for years, first offering a reward for information leading to his capture, then tracking Csatary and painstakingly building up evidence, before turning it over to Hungarian authorities in 2011 and waiting for them to make their own investigation, which spanned over two years.

“In many respects this is one of the most frustrating jobs in the world,” Zuroff said of the long, hard road he’d travelled to bring one Nazi to trial. “It’s like Sisyphus, rolling the stone up the hill, only for it to come back down.”

Reaching the age of 90 doesn’t turn a mass murderer into a righteous gentile.

Zuroff, who estimates he’s played a role in bringing about 40 Nazis to justice over his career, says there are two ways of looking at his efforts. One the one hand, given that tens of thousands of Nazi war criminals escaped trial after World War II, Zuroff says what he’s accomplished is “gurnisht” – nothing. But that’s not how he sees it.

“Look at it differently,” Zuroff says. “Every time a Nazi war criminal is exposed, is indicted, is brought to trial, is punished, it’s a victory for the good guys – for society, for tikkun olam (repairing the world).”

“The passage of time in no way diminishes the guilt of the killers,” Zuroff told Aish.com. “Old age shouldn’t afford protection to people who committed such heinous crimes. Reaching the age of 90-plus doesn’t turn a mass murderer into a righteous gentile.”

In fact, Zuroff recounts that in the many cases he’s worked on, he’s never seen a single Nazi war criminal who ever expressed remorse or contrition. On the contrary: Zuroff’s powerful book Operation Last Chance: One Man’s Quest to Bring Nazi Criminals to Justice details case after case of Nazi war criminals who remained sheltered and protected by sympathetic friends, and even government officials, who continue to aid elderly Nazis even well into the 21st century. (In once case, that of Milivoj Asner, a Croatian Nazi living openly in Austria in the 1990s, Jorg Haider – then a regional governor and later a member of Austria’s ruling coalition government – personally protected the former Nazi and blocked international efforts to bring him to trial.)

In the past few decades, as more has been written and studied about the Holocaust, Zuroff points out, former Nazi officials could easily express remorse if they wished. “These people could say, ‘We made a mistake, we were brainwashed, we thought Jews were the enemy – and we’re sorry.’ But we never had a case of a person who expressed remorse or regret. These are the last people on earth who deserve any sympathy, because they had no sympathy for their victims.”

This dedication to the memory of Nazis victims keeps Zuroff and many of his Nazi-hunting colleagues motivated. “Our obligation is to the victims and that is to find those who turned them into victims,” Zuroff says: “We’ve lost the battle to bring all the Nazis to justice decades ago, but each one we can bring to trial today is a victory.”

If you commit crimes against Jews, the Jewish people will bring you to justice.

Working hard to extend justice to murderers, even decades after their crimes, sends a message to the world that injustice won’t be tolerated. The Nazi hunters at the Simon Wiesenthal Center want to tell the world: “If you commit crimes against the Jewish people, the Jewish people will bring you to justice.”

He stresses this message is universal too, and that all victims – from all countries, ethnicities and religions – deserve justice. The Simon Wiesenthal Center pursues Nazis who killed innocent Roma, Serbs, and other groups during the Holocaust, and Zuroff has consulted on post-genocide nation-building in Rwanda.

In all cases, he warns that allowing murders to go unpunished is a form of “moral pollution” in countries. Nations that have not dealt with citizens who committed crimes against humanity tend to be those with resurgent fascist and anti-Semitic political parties today. “What does it look like with no justice?” he asks. “Look at some nations in eastern Europe today that have very strong fascist parties,” he points out, where Jews and other minorities cannot live safely or even walk about outside without fear of violence: “This is where a refusal to condemn past atrocities can lead.”

In many nations, Zuroff observed, war criminals explain their deeds as acts of patriotism. One function to bringing criminals to trial, therefore, is redefining this distorted view of heroism. “Heroes should be their righteous among the nations,” Zuroff explains. By prosecuting killers, countries are shining a spotlight on criminal acts, and sending a message that xenophobia, torture and murder are incompatible with a civilized society.

Zuroff credits his Jewish faith with motivating him to seek justice for Nazis, even decades after their crimes. “Part of my being an observant Jew goes beyond me praying three times a day, keeping kosher and Shabbat,” Zuroff explains. “Being an observant Jew also means a commitment to the security of the Jewish people, and a mission to make the world a better place.”

He quotes the Torah: “Justice, justice shall you pursue” (Deuteronomy 16:20), and says he often asks himself about the Torah’s choice of words. Why “justice” and why “pursue”? After many years of working to bring some of the most heinous criminals to trial – often against the efforts of obstructionist regional or national officials – Zuroff thinks he’s gained some insights into this crucial Biblical injunction.

Why “pursue”? “Justice doesn’t just fall into your hands,” Zuroff relates. “You have to pursue it and work hard at it.” And why does the Torah say “justice” twice? Zuroff observes: “My interpretation is you have to be an honest broker,” transparent in all your dealings, including efforts to bring Nazis to trial.

We are the last generation who will be able to bring Nazi war criminals to trial. Efraim Zuroff and his colleagues are carrying out this mission on behalf of all of us – the entire Jewish people, and the world – to bring the last living perpetrators of the Holocaust to their final, belated, account.

Further information on the Simon Wiesenthal Center, including information on rewards for information leading to the arrest of Nazi war criminals, can be found at www.operationlastchance.org.